by Boyd Magers Miss Chicago. Earl Carroll showgirl. Restraunteur. Travel agency owner. Registered miniature horse breeder and trainer. Actress. From humble beginnings as Jean Deifel on September 13, 1920, in Montgomery, Illinois (a suburb of Aurora), Carole Mathews did it all and traveled around the world with her accomplishments. But how different it all would have been if she’d followed her first aspirations—to become a nun. “I had no church upbringing, my parents didn’t go to church. But when I went to my grandmother to be raised, I think it was because my mother divorced my father and the two boys, there were four of us in the family, the two boys went with my father and the two girls were given to my mother. My mother took my sister and my grandmother reared me. I can’t recall why, but I remember one day, I went in to my grandmother and said, I want to go to Catholic school, parochial school. And she said why? I don’t know, I just want to go. She said okay, went to the fathers and the nuns, talked to them and made some sort of a deal and I went into Catholicism in the sixth, seventh and eighth grades. During that time, you’re very impressionable. I was a very unhappy child and I thought I had found such peace in the church. I sang in the choir and this and that. I thought, in my young mind, the way to go was to become a nun. I didn’t go for the right reasons, it was just a security thing. By the time I graduated from high school, I went into the nunnery. I went up to Milwaukee to St. Francis. But my grandmother pulled me out and said, wait til you’re twenty-one. In the meantime, I won the title of Miss Chicago. Grandma said, ‘I wish I’d left you in the nunnery,’ after I got in show business. From one extreme to the other. Although show business is not exactly the nunnery, it’s a form of giving. You give of yourself.” “At any rate, some of the kids I went to school with knew I was planning to go into the nunnery and they dared me to put a bathing suit on…$5 to put a bathing suit on and go on the stage. I took it. In those days, $5 was a lot of money. 1938. So I won that the first time I went around. Some of the men there that had something to do with the contest asked me to go to other theaters. They thought they had a winner there. So I went to about three different theaters, Miss Highland, Miss this and that, different theaters, and I won every time. On the day of the finals, my parents came home and they were absolutely against it, they wouldn’t let me go. But the men talked to my parents and they finally relented and said okay. I went in and I won that title. Then, I was qualified to try for Miss America in 1938 but my parents said absolutely not, this had gone far enough. But by winning the title of Miss Chicago, I won a screen test and a trip to California.”

From there Carole did radio in Chicago, modeling (VOGUE, HARPER’S BAZAAR) and was an extra in films before she put her heart into acting. “It was really intermingled. I modeled in Chicago before I went to Hollywood. I appeared at the College Inn in Chicago, that’s how I got into show business, really. Then I had a gentleman friend who owned a lot of products…it was a health thing…and he gave me a job at WGN in Chicago, ‘Breakfast Time With Carole Mathews’. I had that radio show for at least four, five, six months.” As an Earl Carroll showgirl, Carole used her real name, but changed it to Jeanne Francis when she worked as an extra in films circa 1939. “I was an extra with Tyrone Power and Alice Faye in ‘Rose of Washington Square’ (‘39). I was part of an audience. You do extra, you can’t remember all the pictures. I didn’t change my name to Carole Mathews until I was back in Chicago, working, dancing as a rhumba dancer in the Rhumba Casino in Chicago. I traveled back and forth to Chicago quite frequently. If things weren’t working in California, I went back to do something in Chicago.” Dancing came naturally. “When I was with Earl Carroll I was a showgirl but sometimes when they needed a dancer…they were called ponies, they’re smaller, about 5'4", 5'5"…and because dancing was a natural, they asked me if I could sub or fill in for somebody that became sick or ill and I did. It just came natural to me to dance.”

At last firmly entrenched in Hollywood, Carole signed a Columbia contract in 1943. She remembers studio head Harry Cohn. “He didn’t like me at all. I didn’t like him. Actually, when I say I didn’t like him, I was more scared of him than anything. He had roughness…anybody that was rough, I kind of closed…clamped up. I was really kind of independent. If I didn’t like somebody, I wouldn’t laugh at his jokes. My friends said, ‘Carole, just laugh.’ I said, ‘I think they’re stupid!’ I was that innocent, I didn’t play the game. I kind of ruined a lot of opportunities, I think, just by being me.” “The first thing I did was ‘The Girl In the Case’ ('44) for Columbia. I was put under contract to Columbia after I did that. Max Arno, the talent person at Columbia was the one that decided to put me under contract.” Good roles in “The Missing Juror” (‘44), “She’s A Sweetheart” (‘44), “Swing In the Saddle” (‘44) and “I Love A Mystery” (‘45), based on the popular radio series, followed. Carole recalls her first Western. “I was so thrilled. I didn’t have a script. ‘We just want you to do one scene, no dialogue.’ Okay. I waited all day, watching the wranglers, wondering when they were gonna get to me. Finally, around five or six o’clock at night, they said, ‘Carole, time for your scene. All we want you to do is walk through the door.’ No rehearsal. So I walk through the door and they turned a hose on me! They wanted my natural reaction on film. I was soaking wet! That was my introduction to Westerns.”

Even the ladies must know how to ride if you’re doing Westerns, which often leads to some harrowing experiences. “Riding came naturally. I used to ride bareback in the country. I loved animals. I had horses later on in my life. But, a lot of us girls lived at the Studio Club. I was living there and got a job that required riding. I took some western saddle lessons, but I think the man was a masochist. I rode all day! I had on blue jeans. When I came home I was so sore, I was absolutely raw. So, some of the girls said we’ll take care of that and they put Dr. So and So’s medicine on—Well! I nearly went up to the ceiling when they did. The next day I couldn’t get on the horse, but they padded me and I got through the scene.” “I very vividly remember doing one of Charlie Starrett’s Westerns. I was in a house and I was trying to escape. I ran out, jumped on the horse. Remember, I could ride a horse…but I got on a horse that the stirrups were too long, they were adjusted for the wrangler, and I couldn’t gain control. The horse ran right towards some trees, limbs and all that. I didn’t know what to do. I held onto the horn. I lost the reins because I was trying to get to the stirrups. It all happened so fast, but a wrangler got the horse before any accident. I surely would have been killed or hurt.” “I love animals. The only thing I didn’t particularly like about doing Westerns was when a horse was hurt. Once in a while, they did break a leg when they were felled for a scene and they had to put them down. That wasn’t to my taste.” Carole exuded strength on screen before it was the “in thing” to be an independent woman. “I thought I’d be good as another Gale Sondergaard but I never got parts like that. But I was a very strong person because of my background. When you’re trussed from one house to another and one home to another and you don’t know where you’re going, you just have to be tough. It wasn’t until later I realized that it was more of a detriment than an asset.”

Some actors felt being in a serial could hurt their status in the business, but Carole sighs, “I never had a mentor, which I’m sorry to say, I wish I had. It wasn’t in the cards and I’ve always accepted that.” After some 16 films in a two year period, Carole was no longer a Columbia contractee as of late 1945. “I think I had a run-in with the hairdresser. The head hairdresser at Columbia. She’s the one that got me fired. I was in the B-picture level, where Columbia made so many pictures, so when I wanted to get into a higher level, I wasn’t accepted. You’re queen of the B’s and that’s it. So I went to New York (1946-1948) and studied theater and I spent some time in summer stock to learn my craft, thinking that might help.” “I was called to do ‘Whispering Smith’ (‘49) for Paramount with Alan Ladd. I came out but I was too tall for Alan Ladd as a leading lady at that time. The producer didn’t want to hire me because of my height.”

“Another big turning point with my career could have been when I did ‘Meet Me At the Fair’ (‘52) with Dan Dailey. Paul Small, who was a very big agent in Hollywood, called me in and said I want to handle you. I think you’re star material. I spoke to my agent but he wouldn’t sell to Small. My contract had six months to run. Small said we’ll wait six months and I’ll sign you then. But he died within that six months!”

“Then another thing that happened to me in 1942, before I got married, I did a test for Sam Goldwyn. He was interested. I did a scene from ‘Dark Victory’, the 1939 film. The wonderful director Lewis Milestone directed it. Jimmy Wong Howe photographed it. I never saw that test. Jimmy had a Chinese restaurant in the Valley, and that night we all went afterwards to his restaurant. My husband-to-be went along. We got tidily, drinking, and I said, ‘We’re both born on September 13 and we’re going to get married on the 13th.’ He said, ‘Come on, why don’t we get married now?’ Las Vegas was too far to travel so we all decided to drive down to Tijuana to get married. Feeling no pain. We got married, then Goldwyn heard about it, brought me in and said to me, ‘Why did you get married?’ I just looked at him and said, ‘Because I’m in love, I was planning to get married on the 13th anyway.’ So he said, ‘Well, you just lost your contract.’ I never did see the test. Those things do happen in Hollywood. He got upset because I got married. I couldn’t understand it.” Although that role in “Whispering Smith” didn’t pan out, Paramount did use Carole’s talents in a couple of other films including “The Great Gatsby” (1949) with Alan Ladd. “Remember, I’m 5'7" and he was shorter. He stood on a box and I wore tennis shoes." That role led to other good roles in bigger films, such as “Massacre River” (‘49) with Guy Madison and Rory Calhoun. “I liked Guy so much, and Rory. They were like pals. Sometimes you have leading men and all that, but they were friends of mine, pals. We got along very well together. Steve Brodie, playing one of the heavies, had a scene where he opened a door and was supposed to slap me. Instead of a ‘stage slap’, he misjudged the distance and hit me in the face, knocking me out cold. You learned quick in B-movies, if you didn’t duck, you were going to get hit. I saw Guy again when I did ‘Wild Bill Hickok’ TV shows later. Then I did ‘Red Snow’ (‘52) with him.”

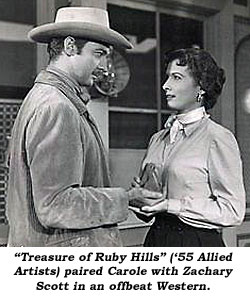

Carole recalls on “Treasure of Ruby Hills” (‘55), “Zachary Scott was really nice. We were just friends, but we used to go out to dinner. He was married at the time to Ruth Ford, I believe.” Another of Carole’s Westerns was “Showdown at Boot Hill” (‘58) with Charles Bronson. “That was funny, because Charles Bronson, when I was doing that, said he was a method actor. He came out of New York. He came up to me, very nicely, ‘I don’t want to throw you, but I never do Like most actresses, Carole moved into the burgeoning new world of television in the early ‘50s. “I rode an elephant on ‘The Cisco Kid’ in 1952.” In the early days of live television, Carole says, “Most of the movie actors were scared of TV because it was like live theatre. But I took to live theatre like a duck to water and really enjoyed live television.” She worked on “G. E. Theatre”, “Playhouse 90”, “Kraft Theatre” and others.

Carole was married in August of 1942. “It was one of those hit and miss things. Getting married just to be married. He came from a very well-to-do family in Chicago and I always thought they never approved of him marrying me. They were very polite, but I never felt accepted. It lasted a couple of years. But we didn’t do anything about it. He went his way and I went my way.” Although Carole never remarried, “I came close to it a couple of times.”

Unemployed from pictures in 1961, Carole got into the travel bureau business. “This gal said, ‘I’m opening up a wholesale travel agency (Hermes Travel in Los Angeles). I’m looking for someone to write brochures for me.’ I said, ‘I’ve traveled all over. I know Europe, give me a job. See how I do.’ In one year, I was the manager. I love to travel, so I loved the business. I think in all my travels, one thing I’ve found out is to be more patient and understanding. People that I don’t understand, I stop to analyze. Where do they come from? Why are they that way? It’s just a little bit more patience. Then I owned my own agency in 1971, with many celebrity accounts…Cher, Flip Wilson, Mac Davis. I ran it up to four million dollars in business and then sold it in 1986. I didn’t know what to do with my money. I had so much money the tax was going to take and friends said, well, invest it in something.” “This is when I got involved with my little horses. In 1982, I was the top champion winner of miniature horses. High points. I had thirteen champion mares. I had a grand champion mare, Britches, and she had a little stallion I called Son of Britches. (Laughs)” As Carole looks back on her multi-faceted life, many things give her pleasure. “For films, I like ‘Meet Me At the Fair’, I would have done that for nothing, and ‘City of Bad Men (1953)’. I liked that gal.”

However, Carole did leave us at 94 on November 6, 2014 in Murrieta, CA. Carole’s Western Filmography Movies: Swing In the Saddle (1944 Columbia)—Big Boy Williams; Blazing the Western Trail (1945 Columbia)—Charles Starrett; Outlaws of the Rockies (1945 Columbia)—Charles Starrett; Sing Me A Song of Texas (1945 Columbia)—Tom Tyler; Massacre River (1949 Allied Artists)—Guy Madison/Rory Calhoun; City of Bad Men (1953 20th Century Fox)—Dale Robertson; Treasure of Ruby Hills (1955 Allied Artists)—Zachary Scott; Showdown at Boot Hill (1958 20th Century Fox)—Charles Bronson; 13 Fighting Men (1960 20th Century Fox)—Grant Williams. Television: Wild Bill Hickok: The Slocum Family (1951); Wild Bill Hickok: Blacksmith Story (1952); Cisco Kid: Pancho and the Pachyderm (1952); Cisco Kid: Dutchman’s Flat (1952); Jim Bowie: The General’s Disgrace (1957); Trackdown: The Farrand Story (1958); Tales of Wells Fargo: The Pickpocket (1958); Man Without A Gun: Lady From Laramie (1958); Zane Grey Theatre: This Man Must Die (1958); The Texan: No Tears For the Dead (1958); Gray Ghost: Greenback Raid (1958); The Californians: series regular (1958-1959); Northwest Passage: The Deserter (1959); Rough Riders: Lesson in Violence (1959); Death Valley Days: A Bullet For the D.A. (1961); Rawhide: Incident at the Odyssey (1964).

|