JACK RANDALL JACK RANDALL

Ratings: Zero to 4 Stars.

RIDERS OF THE DAWN (‘37 Monogram) With the onslaught of Gene Autry at Republic, Dick Foran at Warner Bros. and Fred Scott at Spectrum, Monogram needed a singing cowboy too. They found him in Jack Randall, brother of Bob Livingston who was doing well as part of the Three Mesquiteers at Republic. As Addison Randall, he’d knocked around in small non-western roles for a couple of years. Producer Scotty Dunlap saw in Randall’s good looks and booming baritone voice the makings of a singing cowboy and by September of ‘37, with a name change to the more solid Jack Randall, “Riders of the Dawn” inaugurated the series. On the plus side, “Riders of the Dawn” looked great under Robert N. Bradbury’s direction with excellent photography from Bert Longnecker. The cast included good support work from heavies Warner Richmond and Earl Dwire with busy character player George RIDERS OF THE DAWN (‘37 Monogram) With the onslaught of Gene Autry at Republic, Dick Foran at Warner Bros. and Fred Scott at Spectrum, Monogram needed a singing cowboy too. They found him in Jack Randall, brother of Bob Livingston who was doing well as part of the Three Mesquiteers at Republic. As Addison Randall, he’d knocked around in small non-western roles for a couple of years. Producer Scotty Dunlap saw in Randall’s good looks and booming baritone voice the makings of a singing cowboy and by September of ‘37, with a name change to the more solid Jack Randall, “Riders of the Dawn” inaugurated the series. On the plus side, “Riders of the Dawn” looked great under Robert N. Bradbury’s direction with excellent photography from Bert Longnecker. The cast included good support work from heavies Warner Richmond and Earl Dwire with busy character player George

Cooper as Jack’s (un-fortunately) doomed sidekick, Grizzly, who, as he dies in Jack’s arms, swears, “I’ll be with you at the finish by thunder and lightning!” That especially thrilling finale follows with a running gun battle between outlaws and Jack’s state marshals, topped off by a runaway stagecoach across the salt flats of Lone Pine destroyed by a bolt of lightning amidst the thunder and lightning of a desert storm, all of this pushed to a high level of excitement by Frank Sanucci’s throbbing score. It’s one of the most stimulating climaxes in B-westerns! Unfortunately, the series never again reached this level of art. On the minus side was Randall’s singing voice which exhibited his Broadway stage background, approaching operatic range. Monogram wrongly assumed a more trained singer was a better singing cowboy, ignoring the heartland appeal of real western music that only Gene Autry had exhibited. Protests from theatre exhibitors about Randall’s booming baritone poured in, and Monogram soon dropped his singing in favor of straight action westerns, which under less caring producers (Bob Tansey, Harry Webb) diminished and brought an end to Randall’s B-western career by the close of 1940. Cooper as Jack’s (un-fortunately) doomed sidekick, Grizzly, who, as he dies in Jack’s arms, swears, “I’ll be with you at the finish by thunder and lightning!” That especially thrilling finale follows with a running gun battle between outlaws and Jack’s state marshals, topped off by a runaway stagecoach across the salt flats of Lone Pine destroyed by a bolt of lightning amidst the thunder and lightning of a desert storm, all of this pushed to a high level of excitement by Frank Sanucci’s throbbing score. It’s one of the most stimulating climaxes in B-westerns! Unfortunately, the series never again reached this level of art. On the minus side was Randall’s singing voice which exhibited his Broadway stage background, approaching operatic range. Monogram wrongly assumed a more trained singer was a better singing cowboy, ignoring the heartland appeal of real western music that only Gene Autry had exhibited. Protests from theatre exhibitors about Randall’s booming baritone poured in, and Monogram soon dropped his singing in favor of straight action westerns, which under less caring producers (Bob Tansey, Harry Webb) diminished and brought an end to Randall’s B-western career by the close of 1940.

STARS OVER ARIZONA (‘37 Monogram) The Governor makes Jack a Marshal and paroles four convicts to help him clean up lawless Tuba City. One of them, Earnie Adams, doublecrosses them and sides with Warner Richmond’s outlaws. Routine with a big action finish. Story by Robert Emmett Tansey who reused the paroled convicts idea again in “Blazing Guns” (‘43) with The Trail Blazers and in “Cattle Queen” (‘51). STARS OVER ARIZONA (‘37 Monogram) The Governor makes Jack a Marshal and paroles four convicts to help him clean up lawless Tuba City. One of them, Earnie Adams, doublecrosses them and sides with Warner Richmond’s outlaws. Routine with a big action finish. Story by Robert Emmett Tansey who reused the paroled convicts idea again in “Blazing Guns” (‘43) with The Trail Blazers and in “Cattle Queen” (‘51).

DANGER VALLEY (‘37 Monogram) Randall and pal Hal Price help out a group of desert prospectors led by feisty, strong-willed Lois Wilde and rescue a baby left for dead by the renegades and bring it to Wilde who, as it turns out, is the youngster’s aunt. Unusual for a B-western, Randall and Wilde trade toe to toe barbs and insults before the final clinch. Wilde’s screen career came to a halt several months after “Danger Valley” when she suffered a broken neck in a car accident. She later managed a few bit roles. Disjointed and loaded with stock footage of a gold strike, but Bob Tansey’s unusual script full of lively he/she banter, Wilde’s wonderful performance and the big desert finish from director Robert North Bradbury serve to make it one of Randall’s most interesting B-westerns. DANGER VALLEY (‘37 Monogram) Randall and pal Hal Price help out a group of desert prospectors led by feisty, strong-willed Lois Wilde and rescue a baby left for dead by the renegades and bring it to Wilde who, as it turns out, is the youngster’s aunt. Unusual for a B-western, Randall and Wilde trade toe to toe barbs and insults before the final clinch. Wilde’s screen career came to a halt several months after “Danger Valley” when she suffered a broken neck in a car accident. She later managed a few bit roles. Disjointed and loaded with stock footage of a gold strike, but Bob Tansey’s unusual script full of lively he/she banter, Wilde’s wonderful performance and the big desert finish from director Robert North Bradbury serve to make it one of Randall’s most interesting B-westerns.

WHERE THE WEST BEGINS (‘38 Monogram) Over-the-top Randall with the overused ranch grab plot and plenty of lusty, bad, booming-baritone songs by Jack (5) and lots of love-bantering between Jack and spirited Luana Walters. Problem is, Randall is not Autry and the script doesn’t let Luana be a very likeable character. Jack’s sidekick Fuzzy Knight found a home at Universal and went on to play opposite all their cowboy heroes. The “song” Fuzzy sings here will make you yearn for his Universal silly-tunes, and that’s saying a lot! In the bar, watch for Ray Whitley and his Six-Bar-B Cowboys who quickly saddled up with George O’Brien at RKO. Directed by J. P. McGowan with his usual lack of finesse. WHERE THE WEST BEGINS (‘38 Monogram) Over-the-top Randall with the overused ranch grab plot and plenty of lusty, bad, booming-baritone songs by Jack (5) and lots of love-bantering between Jack and spirited Luana Walters. Problem is, Randall is not Autry and the script doesn’t let Luana be a very likeable character. Jack’s sidekick Fuzzy Knight found a home at Universal and went on to play opposite all their cowboy heroes. The “song” Fuzzy sings here will make you yearn for his Universal silly-tunes, and that’s saying a lot! In the bar, watch for Ray Whitley and his Six-Bar-B Cowboys who quickly saddled up with George O’Brien at RKO. Directed by J. P. McGowan with his usual lack of finesse.

LAND OF FIGHTING MEN (‘38 Monogram) Not available for viewing.

GUNSMOKE TRAIL (‘38 Monogram) After only five outings as a “singing cowboy”, someone at Monogram decided Randall’s operatic style of singing wasn’t conducive to westerns or letters from viewers and comments from exhibitors doomed any further vocalization from Jack. Louise Stanley, now involved with Randall off-screen as well as onscreen, told author Merrill McCord Jack “was very mad” about his westerns being turned into straight action B’s. “Gunsmoke Trail” offers several entertaining touches and moves at a good clip as Jack and pal Fuzzy St. John help out wrongly outlawed bandido Ted Adams who is searching the west for his brother’s killer. Meantime, they also aid beautiful Louise Stanley in saving her father’s ranch. GUNSMOKE TRAIL (‘38 Monogram) After only five outings as a “singing cowboy”, someone at Monogram decided Randall’s operatic style of singing wasn’t conducive to westerns or letters from viewers and comments from exhibitors doomed any further vocalization from Jack. Louise Stanley, now involved with Randall off-screen as well as onscreen, told author Merrill McCord Jack “was very mad” about his westerns being turned into straight action B’s. “Gunsmoke Trail” offers several entertaining touches and moves at a good clip as Jack and pal Fuzzy St. John help out wrongly outlawed bandido Ted Adams who is searching the west for his brother’s killer. Meantime, they also aid beautiful Louise Stanley in saving her father’s ranch.

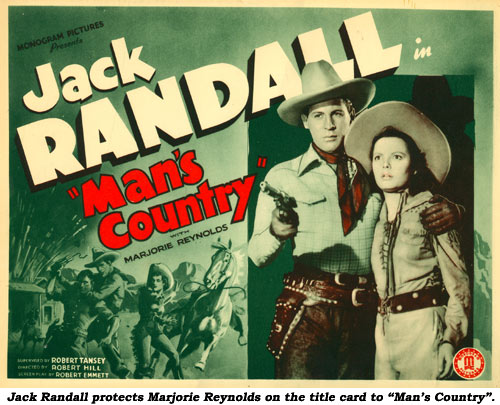

MAN’S COUNTRY (‘38 Monogram) When Dave Sharpe, son of rancher Walter Long, is murdered after being taken into custody by Texas Rangers led by Colonel Forrest Taylor, undercover agent Randall is called in to work with the Rangers to find out who committed the killing of Sharpe—as well as the friend Sharpe was accused of killing. Randall blends in with the outlaws, learning Long has a brother (also played by Walter Long in a dual role). Changing sidekicks film to film, Ralph Peters is Jack’s pal this time. Bit different. Worthwhile. MAN’S COUNTRY (‘38 Monogram) When Dave Sharpe, son of rancher Walter Long, is murdered after being taken into custody by Texas Rangers led by Colonel Forrest Taylor, undercover agent Randall is called in to work with the Rangers to find out who committed the killing of Sharpe—as well as the friend Sharpe was accused of killing. Randall blends in with the outlaws, learning Long has a brother (also played by Walter Long in a dual role). Changing sidekicks film to film, Ralph Peters is Jack’s pal this time. Bit different. Worthwhile.

MEXICALI KID (‘38 Monogram) Jack is tracking down, one by one, the gang who murdered his kid brother in a bank robbery. He’s down to two when he saves a young outlaw, the Mexicali Kid (freckle-faced minor late silent days star Wesley Barry), from heat exhaustion in the desert. The Kid has been sent for by pretty Eleanor Stewart’s ranch manager who is seeking to grab off Stewart’s ranch. Both the Kid and Jack join the gang with Jack pretending to be the long lost heir to the ranch. Although Whip Wilson milked the vengeance theme much better when this story was remade as “Haunted Trails” (‘49), and the action content is only moderate, this is still one of Randall’s better films, owing greatly to the camaraderie of Barry and Randall. This is the first Randall to feature Rusty as his steed—and the horse practically steals the picture performing unlimited tricks, including lifting a pistol from an outlaw’s holster! MEXICALI KID (‘38 Monogram) Jack is tracking down, one by one, the gang who murdered his kid brother in a bank robbery. He’s down to two when he saves a young outlaw, the Mexicali Kid (freckle-faced minor late silent days star Wesley Barry), from heat exhaustion in the desert. The Kid has been sent for by pretty Eleanor Stewart’s ranch manager who is seeking to grab off Stewart’s ranch. Both the Kid and Jack join the gang with Jack pretending to be the long lost heir to the ranch. Although Whip Wilson milked the vengeance theme much better when this story was remade as “Haunted Trails” (‘49), and the action content is only moderate, this is still one of Randall’s better films, owing greatly to the camaraderie of Barry and Randall. This is the first Randall to feature Rusty as his steed—and the horse practically steals the picture performing unlimited tricks, including lifting a pistol from an outlaw’s holster!

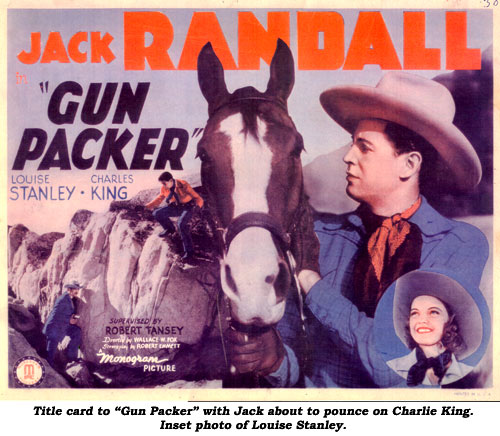

GUN PACKER (‘38 Monogram) Above average Randall outing in which old pro director Wallace Fox makes splendid use of Kernville, CA, locations. U.S. Marshal Randall (and his white-faced intelligent sorrel, Rusty) are called to action when stagecoaches are continuously robbed by Charlie King’s outlaws. The gang, with the aid of Professor Barlowe Borland, recycles the gold through a worked out mine. One question—why is right-handed badman Curley Dresden called Lefty? This B-western holds the distinction of being one of the scant few times a hero has a black sidekick. Raymond Turner, playing mule riding Pinky, began in films about ‘24. Remade 11 years later with Whip Wilson as “Range Land”. GUN PACKER (‘38 Monogram) Above average Randall outing in which old pro director Wallace Fox makes splendid use of Kernville, CA, locations. U.S. Marshal Randall (and his white-faced intelligent sorrel, Rusty) are called to action when stagecoaches are continuously robbed by Charlie King’s outlaws. The gang, with the aid of Professor Barlowe Borland, recycles the gold through a worked out mine. One question—why is right-handed badman Curley Dresden called Lefty? This B-western holds the distinction of being one of the scant few times a hero has a black sidekick. Raymond Turner, playing mule riding Pinky, began in films about ‘24. Remade 11 years later with Whip Wilson as “Range Land”.

WILD HORSE CANYON (‘38 Monogram) Randall rides the vengeance trail with pal Frank Yaconelli (easier to take here than usual as he’s not so “broad”) and finds his quarry working on—and rustling the horses of Dorothy Short’s ranch. Plot points are poorly developed and there’s a tame first half with a lackluster windup to Jack’s long manhunt. Also some terrible over-acting by Dennis Moore when he “wants out” of the gang. WILD HORSE CANYON (‘38 Monogram) Randall rides the vengeance trail with pal Frank Yaconelli (easier to take here than usual as he’s not so “broad”) and finds his quarry working on—and rustling the horses of Dorothy Short’s ranch. Plot points are poorly developed and there’s a tame first half with a lackluster windup to Jack’s long manhunt. Also some terrible over-acting by Dennis Moore when he “wants out” of the gang.

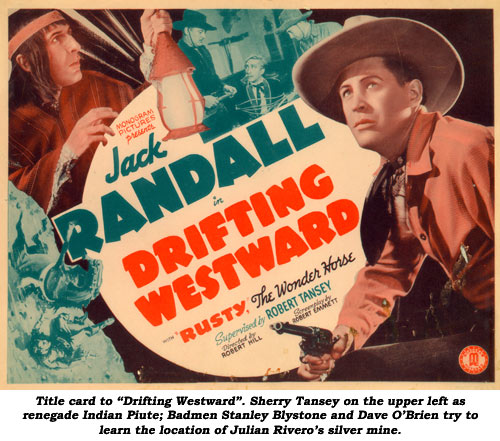

DRIFTING WESTWARD (‘39 Monogram) Randall (and pal Frank Yaconelli) help an old friend of his father’s who is being terrorized as he searches for a map to the hidden Dutchman mine. Dean Spencer, who would soon become Monte “Alamo” Rawlins in “Adventures of the Masked Phantom”, is one of Stanley Blystone’s henchmen. Completely unmemorable except for the scene where Jack is tied up in a cabin with a pack of dynamite about to go off beside him. Rusty the Wonder Horse enters the cabin, picks up the fuse-burning dynamite, trots outside and drops it over a cliff. What a horse! DRIFTING WESTWARD (‘39 Monogram) Randall (and pal Frank Yaconelli) help an old friend of his father’s who is being terrorized as he searches for a map to the hidden Dutchman mine. Dean Spencer, who would soon become Monte “Alamo” Rawlins in “Adventures of the Masked Phantom”, is one of Stanley Blystone’s henchmen. Completely unmemorable except for the scene where Jack is tied up in a cabin with a pack of dynamite about to go off beside him. Rusty the Wonder Horse enters the cabin, picks up the fuse-burning dynamite, trots outside and drops it over a cliff. What a horse!

TRIGGER SMITH (‘39 Monogram) Ex-Marshal Randall goes after the gang that killed Jack’s Marshal brother in a bank robbery. Jack is aided by Mexicali pal Frank Yaconelli, Joyce Byrant and her kid brother, champion junior trick roper and riding whiz Bobby Clack (Clark) in his first film. Take a bathroom break while Yaconelli creaks out a tune. The ending is a real disappointment—mostly lifted from Jack’s “Riders of the Dawn”. Obviously cost-cutting, but it’s jarring, as Jack has been riding Rusty the Wonder Horse earlier in the film, now he has to mount a white horse to match the stock. There’s also footage lifted from Randall’s “Gun Packer” and Tom Keene’s “Where Trails Divide”. Rewritten for the Range Busters’ “Trail Riders”. TRIGGER SMITH (‘39 Monogram) Ex-Marshal Randall goes after the gang that killed Jack’s Marshal brother in a bank robbery. Jack is aided by Mexicali pal Frank Yaconelli, Joyce Byrant and her kid brother, champion junior trick roper and riding whiz Bobby Clack (Clark) in his first film. Take a bathroom break while Yaconelli creaks out a tune. The ending is a real disappointment—mostly lifted from Jack’s “Riders of the Dawn”. Obviously cost-cutting, but it’s jarring, as Jack has been riding Rusty the Wonder Horse earlier in the film, now he has to mount a white horse to match the stock. There’s also footage lifted from Randall’s “Gun Packer” and Tom Keene’s “Where Trails Divide”. Rewritten for the Range Busters’ “Trail Riders”.

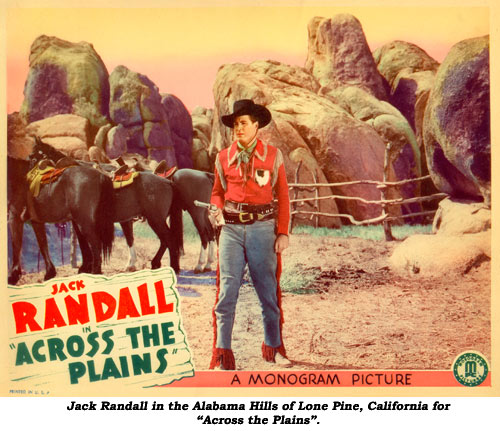

ACROSS THE PLAINS (‘39 Monogram) Superior, fast-paced Randall western in the hands of highly competent director Spencer Gordon Bennet. First and foremost a craftsman, Spence planned every camera set-up well in advance so when he got on location (Lone Pine here) he knew exactly what he wanted. The result is a perfectly lit, dressed and composed film with not a wasted frame, a real treat after several mediocre affairs. Bennet breathes real life into Bob Tansey’s well used young brothers separated after a wagon raid—one grows up good, one bad—script. There’s not an interior shot in the whole film as Bennet makes fabulous use of the Alabams and nearby desert scenery. Dennis Moore is at his best as the all-in-black younger brother who took to the outlaw trail under Robert Card’s misguidance. Bennet’s even able to rein-in most of sidekick Frank Yaconelli’s usual silliness. ACROSS THE PLAINS (‘39 Monogram) Superior, fast-paced Randall western in the hands of highly competent director Spencer Gordon Bennet. First and foremost a craftsman, Spence planned every camera set-up well in advance so when he got on location (Lone Pine here) he knew exactly what he wanted. The result is a perfectly lit, dressed and composed film with not a wasted frame, a real treat after several mediocre affairs. Bennet breathes real life into Bob Tansey’s well used young brothers separated after a wagon raid—one grows up good, one bad—script. There’s not an interior shot in the whole film as Bennet makes fabulous use of the Alabams and nearby desert scenery. Dennis Moore is at his best as the all-in-black younger brother who took to the outlaw trail under Robert Card’s misguidance. Bennet’s even able to rein-in most of sidekick Frank Yaconelli’s usual silliness.

OKLAHOMA TERROR (‘39 Monogram) Randall (investigating the murder of his father) and saddlepal, Al St. John head up a vigilante band to rout land swindlers. Nothing new with most of the action coming at the end. OKLAHOMA TERROR (‘39 Monogram) Randall (investigating the murder of his father) and saddlepal, Al St. John head up a vigilante band to rout land swindlers. Nothing new with most of the action coming at the end.

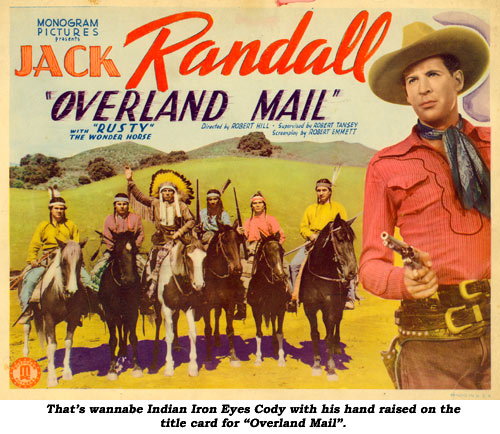

OVERLAND MAIL (‘39 Monogram) Pony Express rider Randall busts up a counterfeiting ring run by Tris Coffin (with a terrible Italian accent!). Rusty the Wonder Horse saves Jack but nothing saves this Monogram meandering. OVERLAND MAIL (‘39 Monogram) Pony Express rider Randall busts up a counterfeiting ring run by Tris Coffin (with a terrible Italian accent!). Rusty the Wonder Horse saves Jack but nothing saves this Monogram meandering.

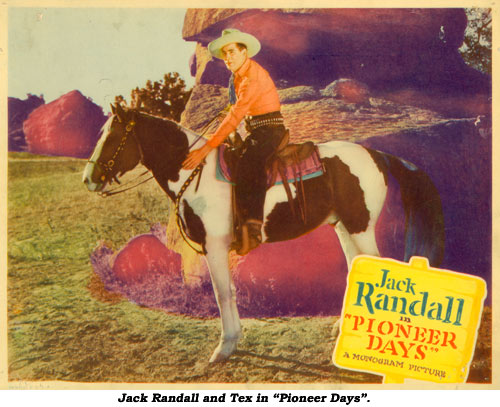

PIONEER DAYS (‘40 Monogram) Uninvolving, sleepy story has express company detective Randall and his two compadres, Frank Yaconelli and Nelson McDowell, investigate a wave of stage holdups and save a girl from being swindled out of inheriting her uncle’s saloon. Monogram apparently lost any real interest in Jack with this entry, the first film of his last series—and with a new producer. The rag-tag Harry S. Webb unit, who had just ground out eight slipshod B’s with Bob Steele under the Metropolitan banner, now held the Randall reins. It was still Webb’s Metropolitan production set-up, with most of his cronies from as far back as the mid-‘20s, simply releasing under the Monogram logo. Webb even replaced Randall’s horse Rusty with a pinto named Tex, a horse Steele had ridden at Metropolitan. Webb had Bennett Cohen touch up a story Cohen had written in ‘34 for Jack Perrin, “Rawhide Mail”. Nelson McDowell must have felt a touch of deja-vu, he was Perrin’s sidekick in the former film. PIONEER DAYS (‘40 Monogram) Uninvolving, sleepy story has express company detective Randall and his two compadres, Frank Yaconelli and Nelson McDowell, investigate a wave of stage holdups and save a girl from being swindled out of inheriting her uncle’s saloon. Monogram apparently lost any real interest in Jack with this entry, the first film of his last series—and with a new producer. The rag-tag Harry S. Webb unit, who had just ground out eight slipshod B’s with Bob Steele under the Metropolitan banner, now held the Randall reins. It was still Webb’s Metropolitan production set-up, with most of his cronies from as far back as the mid-‘20s, simply releasing under the Monogram logo. Webb even replaced Randall’s horse Rusty with a pinto named Tex, a horse Steele had ridden at Metropolitan. Webb had Bennett Cohen touch up a story Cohen had written in ‘34 for Jack Perrin, “Rawhide Mail”. Nelson McDowell must have felt a touch of deja-vu, he was Perrin’s sidekick in the former film.

CHEYENNE KID (‘40 Monogram) The Cheyenne Kid (Randall) swears off gambling and takes a job as foreman at Lafe McKee’s ranch. As Jack takes $1,000 of McKee’s to Louise Stanley’s ranch to buy yearlings, a gang frames him for the murder of Louise’s brother in order to gain control of her ranch. Lackluster with minimal action. For those keeping track of cowboys in drag, Jack dresses as a woman to escape jail. CHEYENNE KID (‘40 Monogram) The Cheyenne Kid (Randall) swears off gambling and takes a job as foreman at Lafe McKee’s ranch. As Jack takes $1,000 of McKee’s to Louise Stanley’s ranch to buy yearlings, a gang frames him for the murder of Louise’s brother in order to gain control of her ranch. Lackluster with minimal action. For those keeping track of cowboys in drag, Jack dresses as a woman to escape jail.

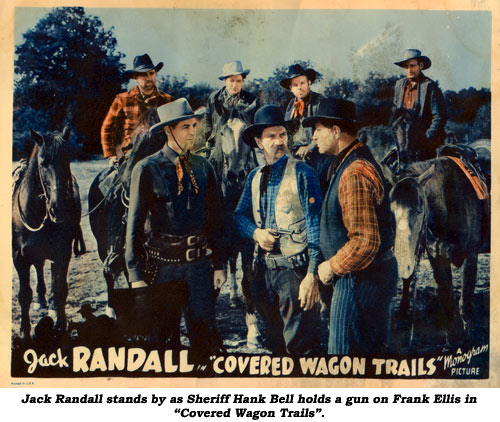

COVERED WAGON TRAILS (‘40 Monogram) This is the Randall that includes the ludicrous scene in which he has to chew his way through ropes that bind him about his wrists. Surely scriptwriters could have been more inventive than this! The Cattlemen’s Association decides to dissuade, at any cost, homesteaders from settling in their valley. When horse trader Randall’s young brother (Dave Sharpe), traveling with the wagon train, is murdered, Jack and pal Budd Buster go after the culprits. Bruce Dane, the cowboy singer who appeared in the Metropolitan Bob Steele “Riders of the Sage” (‘39), pops up again here to sing beside a campfire, apparently for no reason other than to have a song in the film. (Remember, Jack’s singing cowboy days were over by now.) Usual bit player Hank Bell (he of the droopy mustache) has one of his most substantial roles in B-westerns as the Sheriff. COVERED WAGON TRAILS (‘40 Monogram) This is the Randall that includes the ludicrous scene in which he has to chew his way through ropes that bind him about his wrists. Surely scriptwriters could have been more inventive than this! The Cattlemen’s Association decides to dissuade, at any cost, homesteaders from settling in their valley. When horse trader Randall’s young brother (Dave Sharpe), traveling with the wagon train, is murdered, Jack and pal Budd Buster go after the culprits. Bruce Dane, the cowboy singer who appeared in the Metropolitan Bob Steele “Riders of the Sage” (‘39), pops up again here to sing beside a campfire, apparently for no reason other than to have a song in the film. (Remember, Jack’s singing cowboy days were over by now.) Usual bit player Hank Bell (he of the droopy mustache) has one of his most substantial roles in B-westerns as the Sheriff.

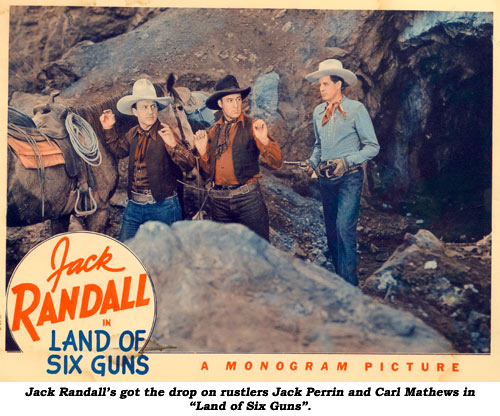

LAND OF THE SIX GUNS (‘40 Monogram) Randall and Louise Stanley were married when they made this one—and it shows. Unfortunately, they didn’t stay that LAND OF THE SIX GUNS (‘40 Monogram) Randall and Louise Stanley were married when they made this one—and it shows. Unfortunately, they didn’t stay that

way. They’d been seeing each other for some time when they were married in February ‘40. They separated in May ‘40 (just when this film was released) with the divorce being final in February ‘41. Cattle rustlers make great use of Bronson Cave. Randall’s sidekick, Glenn Strange, sings a pretty ballad about “Carol”.

KID FROM SANTA FE (‘40 Monogram) When Jack gets on the trail of border smugglers, the boss (Tom London) frames him for the murder of another gang member (George Chesebro). What London doesn’t count on is the spite of Chesebro’s gal pal, Claire Rochelle. Rochelle, who usually appeared as the good girl in B-westerns, gets a chance to ride, shoot and be the bad girl in this one. The “good girl” here, Clarene Curtis, is one of the worst “actresses” we’ve encountered in B-westerns. No wonder this is her only film. However, a very similar looking blonde named Clarisa Curtis was Tex Ritter’s leading lady in “Pals of the Silver Sage”, also Monogram 1940. Also her only film! Were these girls sisters—or is it the same gal with a slight name change? Jack’s ever changing pal this time is Jimmy Aubrey who came from the English music halls to enter films here in 1925. KID FROM SANTA FE (‘40 Monogram) When Jack gets on the trail of border smugglers, the boss (Tom London) frames him for the murder of another gang member (George Chesebro). What London doesn’t count on is the spite of Chesebro’s gal pal, Claire Rochelle. Rochelle, who usually appeared as the good girl in B-westerns, gets a chance to ride, shoot and be the bad girl in this one. The “good girl” here, Clarene Curtis, is one of the worst “actresses” we’ve encountered in B-westerns. No wonder this is her only film. However, a very similar looking blonde named Clarisa Curtis was Tex Ritter’s leading lady in “Pals of the Silver Sage”, also Monogram 1940. Also her only film! Were these girls sisters—or is it the same gal with a slight name change? Jack’s ever changing pal this time is Jimmy Aubrey who came from the English music halls to enter films here in 1925.

RIDERS FROM NO-WHERE (‘40 Monogram) Not available for viewing.

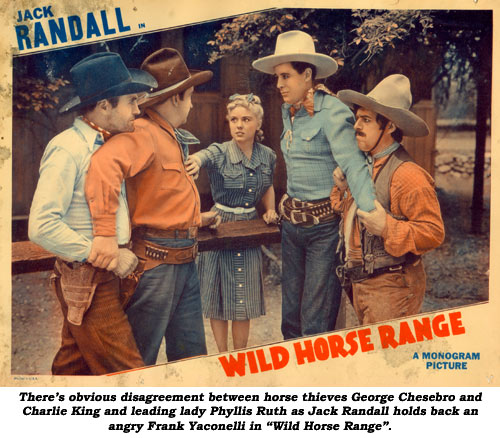

WILD HORSE RANGE (‘40 Mono-gram) Horse trader Jack and sidekick Frank Yaconelli (Oh my God! He’s singing!) capture horse thieves who are stealing herds from ranchers then blaming the losses on a wild white stallion. Pretty routine you’ve-seen-it-all-before stuff. WILD HORSE RANGE (‘40 Mono-gram) Horse trader Jack and sidekick Frank Yaconelli (Oh my God! He’s singing!) capture horse thieves who are stealing herds from ranchers then blaming the losses on a wild white stallion. Pretty routine you’ve-seen-it-all-before stuff.

top of page |