JOHN WAYNE

Ratings: Zero to 4 Stars.

“RANGE FEUD” (‘31 Columbia) Fascinating to see pre-star John Wayne learning the ropes as he’s nearly hung for a murder he didn’t commit in this strong, dramatic Buck Jones B. With overtones of Romeo and Juliet, two Arizona families come to blows over a land dispute that threatens to destroy the romance between Susan Fleming and Wayne. When Fleming’s father is mysteriously murdered and Wayne accused, it’s up to Sheriff Buck Jones to save Wayne from an angry lynch mob. “RANGE FEUD” (‘31 Columbia) Fascinating to see pre-star John Wayne learning the ropes as he’s nearly hung for a murder he didn’t commit in this strong, dramatic Buck Jones B. With overtones of Romeo and Juliet, two Arizona families come to blows over a land dispute that threatens to destroy the romance between Susan Fleming and Wayne. When Fleming’s father is mysteriously murdered and Wayne accused, it’s up to Sheriff Buck Jones to save Wayne from an angry lynch mob.

“TEXAS CYCLONE” (‘32 Columbia) A pure case of mistaken identity as Tim McCoy rides into Stampede where everybody believes he is Jim Rawlins who “disappeared” 5 years ago, even his “wife,” Shirley Grey, who is beset by rustlers. Since he is the spittin’ image of Rawlins, Tim decides to help Grey overcome her rustler problem by pretending to actually be her “lost” husband. It’s a solid story, with a twist ending, aided greatly by watching two developing stars in their salad days—Walter Brennan as a crotchety old Sheriff and Wayne as a fastdraw young ranch hand. Remade by Columbia in ‘37 as “One Man Justice” w/Charles Starrett. “TEXAS CYCLONE” (‘32 Columbia) A pure case of mistaken identity as Tim McCoy rides into Stampede where everybody believes he is Jim Rawlins who “disappeared” 5 years ago, even his “wife,” Shirley Grey, who is beset by rustlers. Since he is the spittin’ image of Rawlins, Tim decides to help Grey overcome her rustler problem by pretending to actually be her “lost” husband. It’s a solid story, with a twist ending, aided greatly by watching two developing stars in their salad days—Walter Brennan as a crotchety old Sheriff and Wayne as a fastdraw young ranch hand. Remade by Columbia in ‘37 as “One Man Justice” w/Charles Starrett.

“TWO FISTED LAW” (‘32 Columbia) In this overly talky B, after losing his ranch to Wheeler Oakman, Tim McCoy leaves, only to discover gold and return to aid neighboring rancher Alice Day and mete out justice to Oakman. A young Wayne has very little to do as one of Tim’s loyal ranch hands. “TWO FISTED LAW” (‘32 Columbia) In this overly talky B, after losing his ranch to Wheeler Oakman, Tim McCoy leaves, only to discover gold and return to aid neighboring rancher Alice Day and mete out justice to Oakman. A young Wayne has very little to do as one of Tim’s loyal ranch hands.

“RIDE HIM, COWBOY” (‘32 Warner Bros.) The first of Wayne’s six film Warner Bros. series is a remake of Ken Maynard’s “Unknown Cavalier” (‘26). The film introduces Duke, Wayne’s horse, who he saves, tames and rides as he tracks down the outlaw responsible for a string of bank robberies, the same one who tried to have Duke destroyed and who is masquerading as a solid citizen. Excellent photography from Ted McCord who lensed dozens of superior Bs with Buck Jones, Tom Keene, Ken Maynard and Dick Foran before becoming an A-film staple at Warner Bros. in the ‘40s. Holding the film back is a protracted, silly trial midway with unfunny Judge Otis Harlan as well as Harry Gribbon miscast as a fearful, bumbling deputy. “RIDE HIM, COWBOY” (‘32 Warner Bros.) The first of Wayne’s six film Warner Bros. series is a remake of Ken Maynard’s “Unknown Cavalier” (‘26). The film introduces Duke, Wayne’s horse, who he saves, tames and rides as he tracks down the outlaw responsible for a string of bank robberies, the same one who tried to have Duke destroyed and who is masquerading as a solid citizen. Excellent photography from Ted McCord who lensed dozens of superior Bs with Buck Jones, Tom Keene, Ken Maynard and Dick Foran before becoming an A-film staple at Warner Bros. in the ‘40s. Holding the film back is a protracted, silly trial midway with unfunny Judge Otis Harlan as well as Harry Gribbon miscast as a fearful, bumbling deputy.

“BIG STAMPEDE” (‘32 Warner Bros.) Wayne rounds up New Mexico cattle rustlers Noah Beery Sr. and Paul Hurst with the aid of a Mexican bandit and massive doses of stock footage from Ken Maynard’s “Land Beyond the Law” (‘27) of which this is a remake. (The film was loosely remade once more by WB in ‘37 as “Land Beyond the Law” w/Dick Foran.) Noah Beery Sr. madly chews up the western scenery as usual. Wayne’s ‘Miracle Horse’ Duke practically steals the show, herding cattle, opening doors and shoving badmen around. Producer of these six Warner Bros. Wayne B’s was Leon Schlesinger who later became famous as producer of the early “Looney Tunes” and “Merrie Melodies” cartoons from Warner Bros. “BIG STAMPEDE” (‘32 Warner Bros.) Wayne rounds up New Mexico cattle rustlers Noah Beery Sr. and Paul Hurst with the aid of a Mexican bandit and massive doses of stock footage from Ken Maynard’s “Land Beyond the Law” (‘27) of which this is a remake. (The film was loosely remade once more by WB in ‘37 as “Land Beyond the Law” w/Dick Foran.) Noah Beery Sr. madly chews up the western scenery as usual. Wayne’s ‘Miracle Horse’ Duke practically steals the show, herding cattle, opening doors and shoving badmen around. Producer of these six Warner Bros. Wayne B’s was Leon Schlesinger who later became famous as producer of the early “Looney Tunes” and “Merrie Melodies” cartoons from Warner Bros.

“HAUNTED GOLD” (‘32 Warner Bros.) There’s plenty of sliding panels, howling wind, spooky shadows, cobwebs, hooded figures, blinking lights, graveyards and secret passages to delight any horror fan as well as the requisite amount (and more) of B-western action as the daughter (Sheila Terry) and son (Wayne) of two old mining partners receive mysterious messages to come to a ghost town loaded with money hungry outlaws and spooky shenanigans. One remarkable, thrilling action sequence high in a cable car above the mine is worth the price of admission alone. Much of it is stock footage from Ken Maynard’s “Phantom City” (‘28) of which this is a remake. Wayne’s sidekick is Blue Washington, one of only two “true” black sidekicks ever in B-westerns. (The other is Fred “Snowflake” Toones.) “Haunted Gold” is far from “politically correct” today with racist slurs such as “watermelon accent”, but it’s nevertheless one of the most entertaining B-westerns ever made. “HAUNTED GOLD” (‘32 Warner Bros.) There’s plenty of sliding panels, howling wind, spooky shadows, cobwebs, hooded figures, blinking lights, graveyards and secret passages to delight any horror fan as well as the requisite amount (and more) of B-western action as the daughter (Sheila Terry) and son (Wayne) of two old mining partners receive mysterious messages to come to a ghost town loaded with money hungry outlaws and spooky shenanigans. One remarkable, thrilling action sequence high in a cable car above the mine is worth the price of admission alone. Much of it is stock footage from Ken Maynard’s “Phantom City” (‘28) of which this is a remake. Wayne’s sidekick is Blue Washington, one of only two “true” black sidekicks ever in B-westerns. (The other is Fred “Snowflake” Toones.) “Haunted Gold” is far from “politically correct” today with racist slurs such as “watermelon accent”, but it’s nevertheless one of the most entertaining B-westerns ever made.

“TELEGRAPH TRAIL” (‘33 Warner Bros.) Cavalry scout Wayne and pal Frank McHugh string telegraph wire while besieged by Indians (yep—Ken Maynard stock). Leading lady Marceline Day has the best role of her B-western career. In the background of one scene, Jack Kirk and friends harmonize on “Mandy Lee”, a song you really want to hear all of…uncluttered by talkover. “TELEGRAPH TRAIL” (‘33 Warner Bros.) Cavalry scout Wayne and pal Frank McHugh string telegraph wire while besieged by Indians (yep—Ken Maynard stock). Leading lady Marceline Day has the best role of her B-western career. In the background of one scene, Jack Kirk and friends harmonize on “Mandy Lee”, a song you really want to hear all of…uncluttered by talkover.

“SOMEWHERE IN SONORA” (‘33 Warner Bros.) Falsely accused of misconduct during a rodeo race, Wayne and his argumentative pals (Frank Rice and Billy Franey whose bantering gets a bit wearisome) ride the trail of missing men to Mexico to find the real culprit, Paul Fix. Previously filmed with Ken Maynard in ‘27, this version utilizes lots of Maynard stock footage—you can plainly see Ken’s face in the scene where Wayne rescues two girls from a runaway buckboard. “SOMEWHERE IN SONORA” (‘33 Warner Bros.) Falsely accused of misconduct during a rodeo race, Wayne and his argumentative pals (Frank Rice and Billy Franey whose bantering gets a bit wearisome) ride the trail of missing men to Mexico to find the real culprit, Paul Fix. Previously filmed with Ken Maynard in ‘27, this version utilizes lots of Maynard stock footage—you can plainly see Ken’s face in the scene where Wayne rescues two girls from a runaway buckboard.

“MAN FROM MONTEREY” (‘33 Warner Bros.) Army Captain Wayne has been dispatched to convince Spanish landowners that lands not registered will fall into public domain. To prevent Lafe McKee from registering his property, Francis Ford has his men kidnap McKee. Wayne wins an unlikely ally in outlaw Charles “Slim” Whitaker and, in the end, calls on the bandit gang to repay a favor by helping him dispatch Ford and his crew. “Comedy” elements with fast-talking fortune teller Luis Alberni are laid on way too thick, and a wedding-breakup-melee finale becomes nearly slapstick in nature. This is a remake of Ken Maynard’s “Canyon of Adventure” (‘28) with Ken and Tarzan replacing John and Duke in some stock footage. A low point for Wayne fans who prefer The Duke in a more traditional western. “MAN FROM MONTEREY” (‘33 Warner Bros.) Army Captain Wayne has been dispatched to convince Spanish landowners that lands not registered will fall into public domain. To prevent Lafe McKee from registering his property, Francis Ford has his men kidnap McKee. Wayne wins an unlikely ally in outlaw Charles “Slim” Whitaker and, in the end, calls on the bandit gang to repay a favor by helping him dispatch Ford and his crew. “Comedy” elements with fast-talking fortune teller Luis Alberni are laid on way too thick, and a wedding-breakup-melee finale becomes nearly slapstick in nature. This is a remake of Ken Maynard’s “Canyon of Adventure” (‘28) with Ken and Tarzan replacing John and Duke in some stock footage. A low point for Wayne fans who prefer The Duke in a more traditional western.

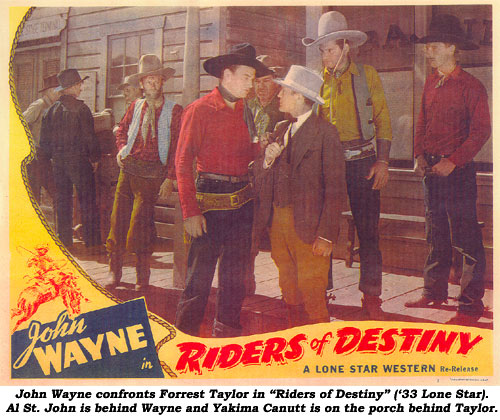

“RIDERS OF DESTINY” (‘33 Lone Star) One of the pivotal B-westerns of all time (along with “In Old Santa Fe”, “Tumbling Tumbleweeds”, “Under Western Stars”, “Three Mesquiteers”, “Song of Old Wyoming”, “Hopalong Cassidy Enters”, etc.). Wayne had just shown he had western “stuff” in co-starring roles with Buck Jones and Tim McCoy, the big budget failure “The Big Trail” and an under appreciated series of six for Warner Bros. But he didn’t seem to be gaining a real foothold on stardom until director Robert N. Bradbury (father of already established Bob Steele) cast Wayne as star of a 16 film series at poverty row Lone Star. Roughhewn action westerns (but ones that hold up to constant viewing lo these many years later), the fast paced Lone Stars gave Wayne further training to develop his screen personality. Here, as Singin’ Sandy, Wayne is wont to break into a somber song of death when the time is ripe for gunplay. The showdown scene between Wayne and Earl Dwire is a minor classic. Certainly Wayne was no vocalist, his voice was dubbed by Bradbury’s son Bill (Bob’s brother), definitely not Smith Ballew as so many “scholars” have proposed. Often misrepresented as a “Singin’ Sandy series”, this was the only time Wayne played that character (although he did “sing” on screen a few times in the future, always dubbed by either Bill Bradbury or, later, Jack Kirk.) At one point, Wayne serenades heroine Cecilia Parker with “Desert Breeze”. This was the first of several pairings for Wayne and George (later Gabby) Hayes. Sometimes in the Lone Stars Hayes was fatherly (as here), other times he was nasty as all get out. “Riders of Destiny”, unfortunately, has it’s missteps, including some badly misplaced slapstick comedy between two outlaws, Al St. John and Heinie Conklin, both ex-Keystone Kops. Director Bradbury definitely goofed there—you just can’t be that overtly comedic with outlaws. This was also the beginning of a lifelong association between Wayne and stuntman/actor Yakima Canutt, seen here as one of the dog heavies and doubling Wayne in several action sequences. Over the course of the Lone Star films, Yak and Wayne developed new routines for filming fight sequences that included carefully chosen camera angles and sharp editing that gave their screen brawls a far more realistic look than had ever before been attained. It was a system all stuntmen and directors quickly adopted. Note also—that’s director Bradbury’s youngest son, Jim, as one of the kids ecstatic about the new river created when Hayes’ well is dynamited. As a historical sidelight, it’s interesting to note these Wayne Lone Stars nearly starred former silent cowboy Buddy Roosevelt. In ‘33 he was all set to sign a contract with Trem Carr (who had produced some of his silent starrers) for the Lone Stars, but Buddy’s wife, Frances, “blew up” at producer Paul Malvern just as Buddy was ready to sign the contract. Her tantrum nixed the deal and eventually caused a divorce. Carr went on to sign Wayne. “RIDERS OF DESTINY” (‘33 Lone Star) One of the pivotal B-westerns of all time (along with “In Old Santa Fe”, “Tumbling Tumbleweeds”, “Under Western Stars”, “Three Mesquiteers”, “Song of Old Wyoming”, “Hopalong Cassidy Enters”, etc.). Wayne had just shown he had western “stuff” in co-starring roles with Buck Jones and Tim McCoy, the big budget failure “The Big Trail” and an under appreciated series of six for Warner Bros. But he didn’t seem to be gaining a real foothold on stardom until director Robert N. Bradbury (father of already established Bob Steele) cast Wayne as star of a 16 film series at poverty row Lone Star. Roughhewn action westerns (but ones that hold up to constant viewing lo these many years later), the fast paced Lone Stars gave Wayne further training to develop his screen personality. Here, as Singin’ Sandy, Wayne is wont to break into a somber song of death when the time is ripe for gunplay. The showdown scene between Wayne and Earl Dwire is a minor classic. Certainly Wayne was no vocalist, his voice was dubbed by Bradbury’s son Bill (Bob’s brother), definitely not Smith Ballew as so many “scholars” have proposed. Often misrepresented as a “Singin’ Sandy series”, this was the only time Wayne played that character (although he did “sing” on screen a few times in the future, always dubbed by either Bill Bradbury or, later, Jack Kirk.) At one point, Wayne serenades heroine Cecilia Parker with “Desert Breeze”. This was the first of several pairings for Wayne and George (later Gabby) Hayes. Sometimes in the Lone Stars Hayes was fatherly (as here), other times he was nasty as all get out. “Riders of Destiny”, unfortunately, has it’s missteps, including some badly misplaced slapstick comedy between two outlaws, Al St. John and Heinie Conklin, both ex-Keystone Kops. Director Bradbury definitely goofed there—you just can’t be that overtly comedic with outlaws. This was also the beginning of a lifelong association between Wayne and stuntman/actor Yakima Canutt, seen here as one of the dog heavies and doubling Wayne in several action sequences. Over the course of the Lone Star films, Yak and Wayne developed new routines for filming fight sequences that included carefully chosen camera angles and sharp editing that gave their screen brawls a far more realistic look than had ever before been attained. It was a system all stuntmen and directors quickly adopted. Note also—that’s director Bradbury’s youngest son, Jim, as one of the kids ecstatic about the new river created when Hayes’ well is dynamited. As a historical sidelight, it’s interesting to note these Wayne Lone Stars nearly starred former silent cowboy Buddy Roosevelt. In ‘33 he was all set to sign a contract with Trem Carr (who had produced some of his silent starrers) for the Lone Stars, but Buddy’s wife, Frances, “blew up” at producer Paul Malvern just as Buddy was ready to sign the contract. Her tantrum nixed the deal and eventually caused a divorce. Carr went on to sign Wayne.

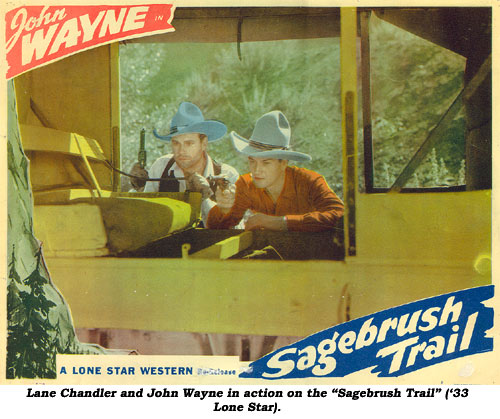

“SAGEBRUSH TRAIL” (‘33 Lone Star) Convicted of a murder he didn’t commit, Wayne flees west pursued by the law while himself pursuing the unknown man actually responsible of the crime for which he is held guilty. Befriended by outlaw Lane Chandler, Wayne reluctantly joins Yakima Canutt’s robber band in hopes of convincing Chandler to go straight. In a spectacular stagecoach chase through a tunnel and over a cliff, Wayne learns Chandler is the man he’s after. Wayne’s second Lone Star western is a remake of Tom Tyler’s “Partners of the Trail” (‘31). Watch for the pre-code nude painting on the cantina wall. Note stuntman Yakima Canutt’s bald spot when he doubles Wayne doing a croupier mount at the start of the film. “SAGEBRUSH TRAIL” (‘33 Lone Star) Convicted of a murder he didn’t commit, Wayne flees west pursued by the law while himself pursuing the unknown man actually responsible of the crime for which he is held guilty. Befriended by outlaw Lane Chandler, Wayne reluctantly joins Yakima Canutt’s robber band in hopes of convincing Chandler to go straight. In a spectacular stagecoach chase through a tunnel and over a cliff, Wayne learns Chandler is the man he’s after. Wayne’s second Lone Star western is a remake of Tom Tyler’s “Partners of the Trail” (‘31). Watch for the pre-code nude painting on the cantina wall. Note stuntman Yakima Canutt’s bald spot when he doubles Wayne doing a croupier mount at the start of the film.

“LUCKY TEXAN” (‘34 Lone Star) Wayne and his blacksmith partner, George Hayes, make a rich gold strike. Assayer Lloyd Whitlock and his henchman bamboozle Hayes into signing away his ranch, then, in debt to Whitlock, Eddie Parker, the son of Sheriff Earl Dwire, robs the banker and kills him laying blame on Hayes just as Hayes’ granddaughter arrives from back east. When Hayes is freed of that charge, the nefarious Whitlock attempts to murder him and blame it on Wayne. Worth the price of admission is one marvelous stunt midway—as Wayne (doubled by Yak) chases Parker, he wildly rides a stick down a log flume into the river. Nothing like it ever before, or since, on screen. “LUCKY TEXAN” (‘34 Lone Star) Wayne and his blacksmith partner, George Hayes, make a rich gold strike. Assayer Lloyd Whitlock and his henchman bamboozle Hayes into signing away his ranch, then, in debt to Whitlock, Eddie Parker, the son of Sheriff Earl Dwire, robs the banker and kills him laying blame on Hayes just as Hayes’ granddaughter arrives from back east. When Hayes is freed of that charge, the nefarious Whitlock attempts to murder him and blame it on Wayne. Worth the price of admission is one marvelous stunt midway—as Wayne (doubled by Yak) chases Parker, he wildly rides a stick down a log flume into the river. Nothing like it ever before, or since, on screen.

“WEST OF THE DIVIDE” (‘34 Lone Star) Wayne and pal George Hayes are searching for the murderer of Wayne’s father and the kidnapper of his baby brother 12 years earlier. There’s more plot and less action to this than most of Wayne’s Lone Stars—but still enuf excitement to satisfy. Lloyd Whitlock is properly dastardly in his attempts to drive Virginia Browne Faire and her father from their ranch. (Note Virginia’s name is incorrect in the credits as Virginia Faire Browne.) Yakima Canutt doubles at times for both Wayne and Whitlock. Larger than usual role for heavy Blackie Whiteford (usually 4th man through the door) as the whip wielding “guardian” of the boy (Billy O’Brien) who turns out to be Wayne’s kid brother. “WEST OF THE DIVIDE” (‘34 Lone Star) Wayne and pal George Hayes are searching for the murderer of Wayne’s father and the kidnapper of his baby brother 12 years earlier. There’s more plot and less action to this than most of Wayne’s Lone Stars—but still enuf excitement to satisfy. Lloyd Whitlock is properly dastardly in his attempts to drive Virginia Browne Faire and her father from their ranch. (Note Virginia’s name is incorrect in the credits as Virginia Faire Browne.) Yakima Canutt doubles at times for both Wayne and Whitlock. Larger than usual role for heavy Blackie Whiteford (usually 4th man through the door) as the whip wielding “guardian” of the boy (Billy O’Brien) who turns out to be Wayne’s kid brother.

“BLUE STEEL” (‘34 Lone Star) Quite likely the best of the Wayne Lone Stars filled with thrilling action and one of the best mystery-angle opening sequences in B-western films. Searching for the notorious Polka-Dot Bandit, Sheriff George Hayes takes refuge from a raging thunderstorm in a halfway-house hotel. Just prior to that, Wayne has also secluded himself in the hotel. During the night, the Polka-Dot (Yakima Canutt) loots the safe of a payroll. Hayes, seeing Wayne give chase to Canutt, mistakes him for the Polka-Dot Bandit. Sometime later, Hayes tracks Wayne down but just as he is about to arrest him, Edward Peil Sr.’s outlaw gang raids Eleanor Hunt and the provisions wagon of her father. Wayne and Hayes help, becoming involved in the rancher’s fight to drive off the outlaws. Peil—who now has Polka-Dot Yak working for him—is trying to stop all provisions from coming into the Valley so he can buy up land at paltry prices. There are several humorous double-entendre jokes early on in the hotel sequence when a pair of newlyweds (Harry Langdon seem-a-like George Nash and his bride) check in. Written and directed by Robert North Bradbury who had used this same plot in Bob Custer’s “Son of the Plains” (‘31). This is far superior to the earlier version in all respects. “BLUE STEEL” (‘34 Lone Star) Quite likely the best of the Wayne Lone Stars filled with thrilling action and one of the best mystery-angle opening sequences in B-western films. Searching for the notorious Polka-Dot Bandit, Sheriff George Hayes takes refuge from a raging thunderstorm in a halfway-house hotel. Just prior to that, Wayne has also secluded himself in the hotel. During the night, the Polka-Dot (Yakima Canutt) loots the safe of a payroll. Hayes, seeing Wayne give chase to Canutt, mistakes him for the Polka-Dot Bandit. Sometime later, Hayes tracks Wayne down but just as he is about to arrest him, Edward Peil Sr.’s outlaw gang raids Eleanor Hunt and the provisions wagon of her father. Wayne and Hayes help, becoming involved in the rancher’s fight to drive off the outlaws. Peil—who now has Polka-Dot Yak working for him—is trying to stop all provisions from coming into the Valley so he can buy up land at paltry prices. There are several humorous double-entendre jokes early on in the hotel sequence when a pair of newlyweds (Harry Langdon seem-a-like George Nash and his bride) check in. Written and directed by Robert North Bradbury who had used this same plot in Bob Custer’s “Son of the Plains” (‘31). This is far superior to the earlier version in all respects.

“MAN FROM UTAH” (‘34 Lone Star) The low point of the Wayne Lone Star series, packed with some 10-12 minutes of rodeo stock footage. Marshal George Hayes enlists the aid of out-of-work Wayne to catch a gang of rodeo crooks. Bill Bradbury, the son of director Robert North Bradbury, does the actual singing for Wayne on the oft repeated “Desert Breeze” which Bradbury’s other son, Bob Steele, warbled in “Western Justice” (‘35) and Wayne “sang” in “Riders of Destiny” (‘33). I figure director Bradbury penned the song and used it wherever he could. The story was remade in ‘44 as “Utah Kid” with Bob Steele and Hoot Gibson. “MAN FROM UTAH” (‘34 Lone Star) The low point of the Wayne Lone Star series, packed with some 10-12 minutes of rodeo stock footage. Marshal George Hayes enlists the aid of out-of-work Wayne to catch a gang of rodeo crooks. Bill Bradbury, the son of director Robert North Bradbury, does the actual singing for Wayne on the oft repeated “Desert Breeze” which Bradbury’s other son, Bob Steele, warbled in “Western Justice” (‘35) and Wayne “sang” in “Riders of Destiny” (‘33). I figure director Bradbury penned the song and used it wherever he could. The story was remade in ‘44 as “Utah Kid” with Bob Steele and Hoot Gibson.

“RANDY RIDES ALONE” (‘34 Lone Star) One of the most entertaining of Wayne’s early Lone Stars as he plays an express agent riding alone to corral a gang who, in a bloodthirsty massacre, have left several persons murdered at Halfway House while looking for a strong box. Charged with the murders himself, Wayne is arrested by the posse led by Marvin Black (alias Matt the Mute, the real head of the outlaw band—played by George Hayes). Freed by Alberta Vaughn, daughter of the murdered Halfway House owner who knows Wayne to be innocent, Wayne hooks up with the gang in a hideout behind a waterfall, eventually bringing them to justice. Notice Wayne’s plaid shirt changes back and forth several times. “RANDY RIDES ALONE” (‘34 Lone Star) One of the most entertaining of Wayne’s early Lone Stars as he plays an express agent riding alone to corral a gang who, in a bloodthirsty massacre, have left several persons murdered at Halfway House while looking for a strong box. Charged with the murders himself, Wayne is arrested by the posse led by Marvin Black (alias Matt the Mute, the real head of the outlaw band—played by George Hayes). Freed by Alberta Vaughn, daughter of the murdered Halfway House owner who knows Wayne to be innocent, Wayne hooks up with the gang in a hideout behind a waterfall, eventually bringing them to justice. Notice Wayne’s plaid shirt changes back and forth several times.

“STAR PACKER” (‘34 Lone Star) The mysterious “STAR PACKER” (‘34 Lone Star) The mysterious

outlaw leader, The Shadow, gives orders to his henchmen from a secret panel behind a wall safe in the back room of the saloon. There’s also a secret tunnel under the room leading to a hollowed out old tree stump in the street from which The Shadow ambushes his enemies—like Marshal Wayne. Stuntman Yakima Canutt gets a real workout here—playing Wayne’s (“Hi You Skookum—Big Fun”) Indian pal (Yak), doubling Wayne, George Hayes and probably others. The whole exciting ending was reused 16 years later for Jimmy Ellison’s “Crooked River” (‘50).

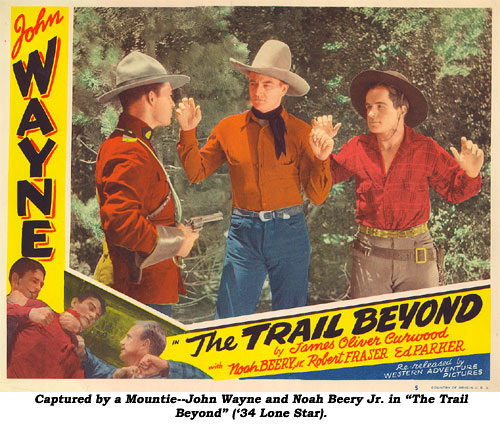

“TRAIL BEYOND” (‘34 Lone Star) Gorgeous locations, terrific action and a solid story. Contains the classic scene during the final chase when Yakima Canutt (doubling for Wayne) gets his spur hung up in his stirrup when attempting a horse to wagon transfer. Director Robert Bradbury left the mishap in as Yak (Wayne) scrambles back onto his horse and tries again—this time successfully. Wayne seems to spend as much time in the water as he does on land when he rescues Noah Beery Jr. from cardsharps and the two go on a quest for a missing girl, Verna Hillie. The “Gat Ganns” reward poster from Wayne’s earlier “West of the Divide” can be spotted on the wall of Noah Beery Sr.’s trading post. Loosely adapted from James Oliver Curwood’s “Wolf Hunters” first filmed in ‘26 and again in ‘49 with Kirby Grant. “TRAIL BEYOND” (‘34 Lone Star) Gorgeous locations, terrific action and a solid story. Contains the classic scene during the final chase when Yakima Canutt (doubling for Wayne) gets his spur hung up in his stirrup when attempting a horse to wagon transfer. Director Robert Bradbury left the mishap in as Yak (Wayne) scrambles back onto his horse and tries again—this time successfully. Wayne seems to spend as much time in the water as he does on land when he rescues Noah Beery Jr. from cardsharps and the two go on a quest for a missing girl, Verna Hillie. The “Gat Ganns” reward poster from Wayne’s earlier “West of the Divide” can be spotted on the wall of Noah Beery Sr.’s trading post. Loosely adapted from James Oliver Curwood’s “Wolf Hunters” first filmed in ‘26 and again in ‘49 with Kirby Grant.

“THE LAWLESS FRONTIER” (‘34 Lone Star) Lotsa good stunt work by Yakima Canutt, doubling Wayne—including a belly-flop ride on a board down a water drainage chute. Wayne chases the half breed Apache outlaw Zanti (Earl Dwire) who has murdered Wayne’s parents, and aids old rancher George Hayes and his daughter (the talented Sheila Terry) whom Zanti plans to rob and abduct, finally bringing the evil Zanti to justice after a chase across Red Rock Canyon desert. “THE LAWLESS FRONTIER” (‘34 Lone Star) Lotsa good stunt work by Yakima Canutt, doubling Wayne—including a belly-flop ride on a board down a water drainage chute. Wayne chases the half breed Apache outlaw Zanti (Earl Dwire) who has murdered Wayne’s parents, and aids old rancher George Hayes and his daughter (the talented Sheila Terry) whom Zanti plans to rob and abduct, finally bringing the evil Zanti to justice after a chase across Red Rock Canyon desert.

“‘NEATH THE ARIZONA SKIES” (‘34 Lone Star) In search of the father of the half breed girl (Shirley Jane Rickert) he has raised since infancy, Wayne is overtaken by Yakima Canutt’s outlaws who learn the youngster is heir to $50,000 in oil leases. Convoluted plot which was filmed before as “Circle Canyon” (‘33) with Buddy Roosevelt but Harry Fraser’s direction here brings out and clarifies important plot points only vaguely hinted at in the previous version. “‘NEATH THE ARIZONA SKIES” (‘34 Lone Star) In search of the father of the half breed girl (Shirley Jane Rickert) he has raised since infancy, Wayne is overtaken by Yakima Canutt’s outlaws who learn the youngster is heir to $50,000 in oil leases. Convoluted plot which was filmed before as “Circle Canyon” (‘33) with Buddy Roosevelt but Harry Fraser’s direction here brings out and clarifies important plot points only vaguely hinted at in the previous version.

“TEXAS TERROR” (‘34 Lone Star) Slower and tamer than many of Wayne’s Lone Star epics. Sheriff Wayne, pursuing bandits, believes he’s accidentally killed his old friend whose daughter, Lucile Browne, is arriving from the East. In reality, outlaw LeRoy Mason is the real killer, but Wayne, torn with anguish and believing the worst, turns in his badge to new Sheriff George Hayes and retreats to the life of an unkempt desert recluse. Hayes convinces Wayne he can make up for the past by becoming Lucile’s foreman so the ranch will flourish. So he does, but through the conniving Mason, Lucile is convinced Wayne killed her father. Remade as Bob Baker’s “Guilty Trail” (‘38). “TEXAS TERROR” (‘34 Lone Star) Slower and tamer than many of Wayne’s Lone Star epics. Sheriff Wayne, pursuing bandits, believes he’s accidentally killed his old friend whose daughter, Lucile Browne, is arriving from the East. In reality, outlaw LeRoy Mason is the real killer, but Wayne, torn with anguish and believing the worst, turns in his badge to new Sheriff George Hayes and retreats to the life of an unkempt desert recluse. Hayes convinces Wayne he can make up for the past by becoming Lucile’s foreman so the ranch will flourish. So he does, but through the conniving Mason, Lucile is convinced Wayne killed her father. Remade as Bob Baker’s “Guilty Trail” (‘38).

“RAINBOW VALLEY” (‘35 Lone Star) Undercover agent Wayne helps isolated townspeople build a road through to the next town to bring law and order to a valley dominated by gunmen. Wayne is aided by mail carrier George Hayes in his Model T Ford from which, at one point, Hayes chases the badmen throwing dynamite at them. “RAINBOW VALLEY” (‘35 Lone Star) Undercover agent Wayne helps isolated townspeople build a road through to the next town to bring law and order to a valley dominated by gunmen. Wayne is aided by mail carrier George Hayes in his Model T Ford from which, at one point, Hayes chases the badmen throwing dynamite at them.

“DESERT TRAIL” (‘35 Lone Star) Nervy rodeo rider John Wayne and his pal, gambler Eddy Chandler, are falsely accused in the robbery of the rodeo prize money and murder of the clerk, a crime really committed by stick-up men Al Ferguson and Paul Fix. Wayne trails Ferguson to where Fix lives with his sister, Mary Kornman. Fix wants to go straight but Ferguson blackmails him into committing a stagecoach robbery—for which Wayne and Chandler are also blamed! Not Wayne’s finest Lone Star hour with a weaker than usual supporting cast. Director Cullin (or Cullen) Lewis was better known as Lewis Collins (1897-1954) who worked steadily from ‘30 til his death. He’s notable for directing what some consider the last series B-western, “Two Guns and a Badge” w/Wayne Morris just before his death. “DESERT TRAIL” (‘35 Lone Star) Nervy rodeo rider John Wayne and his pal, gambler Eddy Chandler, are falsely accused in the robbery of the rodeo prize money and murder of the clerk, a crime really committed by stick-up men Al Ferguson and Paul Fix. Wayne trails Ferguson to where Fix lives with his sister, Mary Kornman. Fix wants to go straight but Ferguson blackmails him into committing a stagecoach robbery—for which Wayne and Chandler are also blamed! Not Wayne’s finest Lone Star hour with a weaker than usual supporting cast. Director Cullin (or Cullen) Lewis was better known as Lewis Collins (1897-1954) who worked steadily from ‘30 til his death. He’s notable for directing what some consider the last series B-western, “Two Guns and a Badge” w/Wayne Morris just before his death.

“DAWN RIDER” (‘35 Lone Star) Wayne returns after a long absence to see his father and winds up crossways between two men. One of them, Dennis Moore (still using the moniker Denny Meadows), kills Wayne’s Dad in a daring express company holdup and turns out to be the brother of a girl for whom Wayne has fallen. The other, Reed Howes, is John’s best friend who also has eyes for the girl. Strong story, good characterizations, hard action and some thrilling stunts by Yakima Canutt make this one of Wayne’s best Lone Stars. Wayne’s younger brother, Bob Morrison (1911-1970) has a bit role. As Wayne became a top star, he always placed his seemingly unambitious brother in various production positions at Wayne-Fellows and Batjac. Morrison is listed as producer on “Seven Men From Now” (‘56), “Gun the Man Down” (‘57) and “Escort West” (‘59). “DAWN RIDER” (‘35 Lone Star) Wayne returns after a long absence to see his father and winds up crossways between two men. One of them, Dennis Moore (still using the moniker Denny Meadows), kills Wayne’s Dad in a daring express company holdup and turns out to be the brother of a girl for whom Wayne has fallen. The other, Reed Howes, is John’s best friend who also has eyes for the girl. Strong story, good characterizations, hard action and some thrilling stunts by Yakima Canutt make this one of Wayne’s best Lone Stars. Wayne’s younger brother, Bob Morrison (1911-1970) has a bit role. As Wayne became a top star, he always placed his seemingly unambitious brother in various production positions at Wayne-Fellows and Batjac. Morrison is listed as producer on “Seven Men From Now” (‘56), “Gun the Man Down” (‘57) and “Escort West” (‘59).

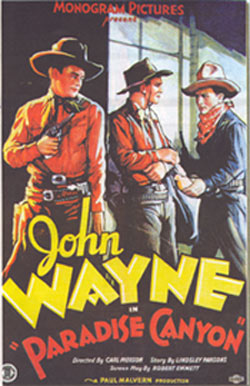

“PARADISE CANYON” (‘35 Lone Star) If you only obtain one B-western with Earle Hodgins’ Indian remedy Medicine Show spiel, this is the one! He’s so effective here, I had my dollar out ready to purchase a bottle of his cure-all tonic! Federal agent Wayne, on the trail of some counterfeiters, joins Hodgins’ Medicine show as a sharpshooter. The show also features Hodgins’ daughter and two musical entertainers, Perry Murdock and Gordon Clifford, who sing two numbers. Portions of the plot were lifted and used in Tim McCoy’s “Border Caballero” (‘36) while the whole idea was reworked (poorly) by Bob Tansey for Ken Maynard’s last B-western, “Harmony Trail” (‘44). These Wayne Lone Stars have been reissued many times—some of the bastardized versions feature new music, have been colorized and even added replacement voices for Wayne and others! But you’ll want to find them in their pure, original form to enjoy their energetic, raw charm. “PARADISE CANYON” (‘35 Lone Star) If you only obtain one B-western with Earle Hodgins’ Indian remedy Medicine Show spiel, this is the one! He’s so effective here, I had my dollar out ready to purchase a bottle of his cure-all tonic! Federal agent Wayne, on the trail of some counterfeiters, joins Hodgins’ Medicine show as a sharpshooter. The show also features Hodgins’ daughter and two musical entertainers, Perry Murdock and Gordon Clifford, who sing two numbers. Portions of the plot were lifted and used in Tim McCoy’s “Border Caballero” (‘36) while the whole idea was reworked (poorly) by Bob Tansey for Ken Maynard’s last B-western, “Harmony Trail” (‘44). These Wayne Lone Stars have been reissued many times—some of the bastardized versions feature new music, have been colorized and even added replacement voices for Wayne and others! But you’ll want to find them in their pure, original form to enjoy their energetic, raw charm.

“WESTWARD HO” (‘35 Republic) Probably the best of the “separated brothers” sub-genre of B-westerns. Jack Curtis and Yakima Canutt’s trail-jumpers raid a wagon train, murder the parents of youngsters Wayne and Frank McGlynn Jr., fire the wagons and kidnap young McGlynn. Years later, Curtis has raised McGlynn to be the right hand man of his gang with McGlynn never knowing Curtis was guilty of the heinous crime. Mean-while, Wayne grows up and organizes a band of white horse vigilantes called the Singing Riders (Jack Kirk and his boys do the vocal work) ridding the west of outlaw gangs, constantly searching for Curtis and Wayne’s lost brother. Eventually, the brothers are reunited when Curtis tricks and doublecrosses McGlynn into wiping out the Riders including his own brother. A compelling story and some spectacular stuntwork make this really worthwhile… except for the ludicrous scene when Wayne strums a guitar and “sings” (in Jack Kirk’s voice) a song. “WESTWARD HO” (‘35 Republic) Probably the best of the “separated brothers” sub-genre of B-westerns. Jack Curtis and Yakima Canutt’s trail-jumpers raid a wagon train, murder the parents of youngsters Wayne and Frank McGlynn Jr., fire the wagons and kidnap young McGlynn. Years later, Curtis has raised McGlynn to be the right hand man of his gang with McGlynn never knowing Curtis was guilty of the heinous crime. Mean-while, Wayne grows up and organizes a band of white horse vigilantes called the Singing Riders (Jack Kirk and his boys do the vocal work) ridding the west of outlaw gangs, constantly searching for Curtis and Wayne’s lost brother. Eventually, the brothers are reunited when Curtis tricks and doublecrosses McGlynn into wiping out the Riders including his own brother. A compelling story and some spectacular stuntwork make this really worthwhile… except for the ludicrous scene when Wayne strums a guitar and “sings” (in Jack Kirk’s voice) a song.

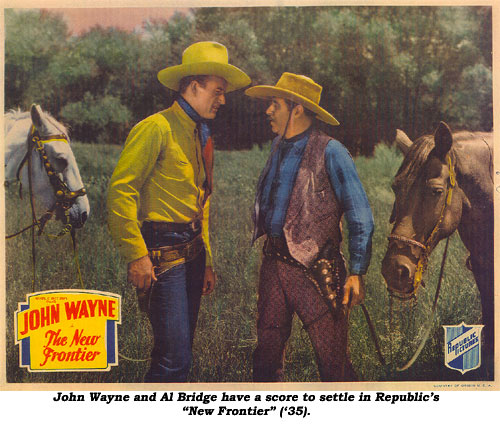

“THE NEW FRONTIER” (‘35 Republic) Wayne, trying to follow in his father’s path as leader of pioneer caravans, becomes a sheriff when his father is murdered by gambling hall boss Warner Richmond (at his snide best). To clean up the town, Wayne enlists the aid of another outlaw leader, Al Bridge, who has an old score to settle with Richmond which he does in a wild gun blazing finish amidst a town in flames. Not to be confused with Wayne’s 3 Mesquiteers ‘39 Republic of the same name. “THE NEW FRONTIER” (‘35 Republic) Wayne, trying to follow in his father’s path as leader of pioneer caravans, becomes a sheriff when his father is murdered by gambling hall boss Warner Richmond (at his snide best). To clean up the town, Wayne enlists the aid of another outlaw leader, Al Bridge, who has an old score to settle with Richmond which he does in a wild gun blazing finish amidst a town in flames. Not to be confused with Wayne’s 3 Mesquiteers ‘39 Republic of the same name.

“LAWLESS RANGE” (‘35 Republic) Non-stop action as Wayne comes to help his Dad’s old friend and finds him missing. Undercover, John helps the Uncle’s niece and the other ranchers in their fight against outlaws who are trying to drive them out for the gold they know is on their land. John “sings” two songs in this one—actually performed by Jack Kirk who, with his group, The Wranglers (Glenn Strange, Charley Sargent, Chuck Baldra), sing one other song. One of the songs, a mournful one about an outlaw “drinkin’ his drinks with the dead” is the same song used in “Riders of Destiny” (‘33). Obviously, director Bradbury liked the idea and reused it here, again with Wayne riding alone across the desert. Previously, though, the song was warbled by Bradbury’s son, Bill. Another recycled idea from Bradbury is having two groups of dismounted men fight a running gun battle in a long culvert. Bradbury used it earlier in ‘35 for Wayne’s “Rainbow Valley” and yet again in Tex Ritter’s “Riders of the Rockies” (‘37). “LAWLESS RANGE” (‘35 Republic) Non-stop action as Wayne comes to help his Dad’s old friend and finds him missing. Undercover, John helps the Uncle’s niece and the other ranchers in their fight against outlaws who are trying to drive them out for the gold they know is on their land. John “sings” two songs in this one—actually performed by Jack Kirk who, with his group, The Wranglers (Glenn Strange, Charley Sargent, Chuck Baldra), sing one other song. One of the songs, a mournful one about an outlaw “drinkin’ his drinks with the dead” is the same song used in “Riders of Destiny” (‘33). Obviously, director Bradbury liked the idea and reused it here, again with Wayne riding alone across the desert. Previously, though, the song was warbled by Bradbury’s son, Bill. Another recycled idea from Bradbury is having two groups of dismounted men fight a running gun battle in a long culvert. Bradbury used it earlier in ‘35 for Wayne’s “Rainbow Valley” and yet again in Tex Ritter’s “Riders of the Rockies” (‘37).

“OREGON TRAIL” (‘36 Republic) Not available for viewing.

“LAWLESS NINETIES” (‘36 Republic) Lawless elements are opposed to Wyoming statehood as it would spell the end to their illegal activities. Crusading newspaperman George Hayes supports statehood and opposes the crooked politics. Just before the statehood election, the government sends in two G-Men of the range, Wayne and Lane Chandler, to ensure an honest election. The lawless element fights back, murdering both Chandler and Hayes, but their political corruption and crooked dealings backfire. “LAWLESS NINETIES” (‘36 Republic) Lawless elements are opposed to Wyoming statehood as it would spell the end to their illegal activities. Crusading newspaperman George Hayes supports statehood and opposes the crooked politics. Just before the statehood election, the government sends in two G-Men of the range, Wayne and Lane Chandler, to ensure an honest election. The lawless element fights back, murdering both Chandler and Hayes, but their political corruption and crooked dealings backfire.

“KING OF THE PECOS” (‘36 Republic) Law student Wayne returns home to avenge the murder before his eyes of his parents by local cattle baron Cy Kendall who claims a vast empire by right of discovery—and violence. When law books fail, Wayne turns to gun law to bring Kendall to justice. Rewritten for Don Barry’s “Texas Terrors” (‘40). “KING OF THE PECOS” (‘36 Republic) Law student Wayne returns home to avenge the murder before his eyes of his parents by local cattle baron Cy Kendall who claims a vast empire by right of discovery—and violence. When law books fail, Wayne turns to gun law to bring Kendall to justice. Rewritten for Don Barry’s “Texas Terrors” (‘40).

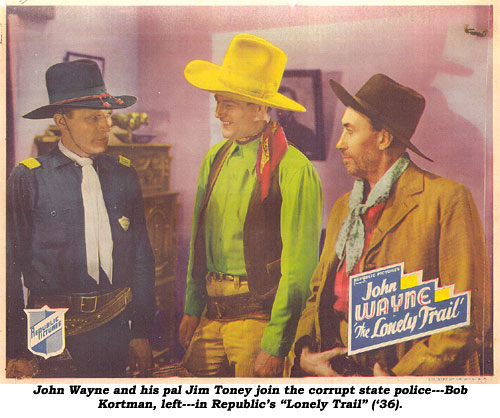

“LONELY TRAIL” (‘36 Republic) Following the Civil War, carpetbaggers gain control of a part of Texas where they terrorize citizens with their state police through a tax collection system of legalized murder and oppression. Returning home, former Union officer Wayne joins the state police to fight illegalities from within. In the unusual sidekick category is Wayne’s lanky, rustic Civil War buddy, Jim Toney, who plays it fairly straight in the vein of Raymond Hatton or Eddy Waller. “LONELY TRAIL” (‘36 Republic) Following the Civil War, carpetbaggers gain control of a part of Texas where they terrorize citizens with their state police through a tax collection system of legalized murder and oppression. Returning home, former Union officer Wayne joins the state police to fight illegalities from within. In the unusual sidekick category is Wayne’s lanky, rustic Civil War buddy, Jim Toney, who plays it fairly straight in the vein of Raymond Hatton or Eddy Waller.

“WINDS OF THE WASTELAND” (‘36 Republic) With the cessation of the Pony Express, two of its best riders, Wayne and Lane Chandler, decide to pool their dough and go partners in a stagecoach-line business. They are snookered out of their $1,000 by a crooked stageline owner who pawns off to them a franchise which turns out to be a near ghost town. Undiscouraged, Wayne and Chandler fight back by entering in a Republic staple—the stagecoach race for the government mail contract. Possibly the best use ever of the Brandeis location ranch which often “played” a ghost town in B-westerns. Watch early on for a bit by Charles Locher—later Jon Hall—as a pony rider. Stupid line: One pony rider to another: “He’s due here in 10 seconds!” Really? Didn’t know those Pony Express riders were quite that accurate on their arrivals. “WINDS OF THE WASTELAND” (‘36 Republic) With the cessation of the Pony Express, two of its best riders, Wayne and Lane Chandler, decide to pool their dough and go partners in a stagecoach-line business. They are snookered out of their $1,000 by a crooked stageline owner who pawns off to them a franchise which turns out to be a near ghost town. Undiscouraged, Wayne and Chandler fight back by entering in a Republic staple—the stagecoach race for the government mail contract. Possibly the best use ever of the Brandeis location ranch which often “played” a ghost town in B-westerns. Watch early on for a bit by Charles Locher—later Jon Hall—as a pony rider. Stupid line: One pony rider to another: “He’s due here in 10 seconds!” Really? Didn’t know those Pony Express riders were quite that accurate on their arrivals.

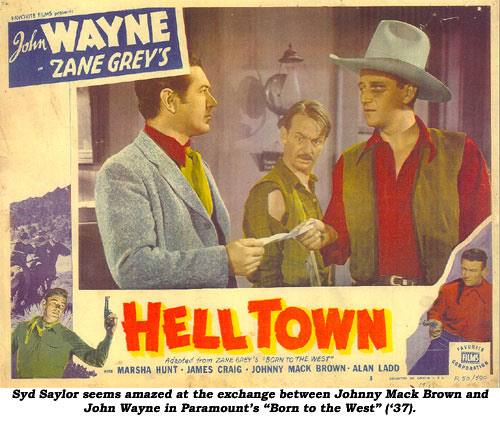

“BORN TO THE WEST” (re-released as “HELL TOWN”) (‘37 Paramount) Good script, good actors, good direction lift this Zane Grey entry into near A territory. Drifter Wayne straightens out his slightly wayward life and woos Marsha Hunt when he becomes trail boss for his banker/rancher cousin Johnny Mack Brown, who has to rescue Wayne from saloon owner/rustler Monte Blue and card cheat James Craig before it’s all over. Alan Ladd is listed in a bit role, but I defy you to spot him. Syd Saylor as Wayne’s sidekick provides a few laughs as a lightning rod salesman. “BORN TO THE WEST” (re-released as “HELL TOWN”) (‘37 Paramount) Good script, good actors, good direction lift this Zane Grey entry into near A territory. Drifter Wayne straightens out his slightly wayward life and woos Marsha Hunt when he becomes trail boss for his banker/rancher cousin Johnny Mack Brown, who has to rescue Wayne from saloon owner/rustler Monte Blue and card cheat James Craig before it’s all over. Alan Ladd is listed in a bit role, but I defy you to spot him. Syd Saylor as Wayne’s sidekick provides a few laughs as a lightning rod salesman.

“PALS OF THE SADDLE” (‘38 Republic) Modern west 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Ray Corrigan, Max Terhune) adventure as deadly Monium gas threatens the nation. In Wayne’s first outing as a Mesquiteer (replacing Robert Livingston), he and his pals stumble onto a plan by an evil judge to export the deadly chemical to Mexico to sell to foreign interests. When Wayne is framed for a murder his only escape route is to fake his own death. The thrill and stunt packed windup in Red Rock Canyon is a stunner. Remade as “Song of the Range” (‘44) with Jimmy Wakely. “PALS OF THE SADDLE” (‘38 Republic) Modern west 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Ray Corrigan, Max Terhune) adventure as deadly Monium gas threatens the nation. In Wayne’s first outing as a Mesquiteer (replacing Robert Livingston), he and his pals stumble onto a plan by an evil judge to export the deadly chemical to Mexico to sell to foreign interests. When Wayne is framed for a murder his only escape route is to fake his own death. The thrill and stunt packed windup in Red Rock Canyon is a stunner. Remade as “Song of the Range” (‘44) with Jimmy Wakely.

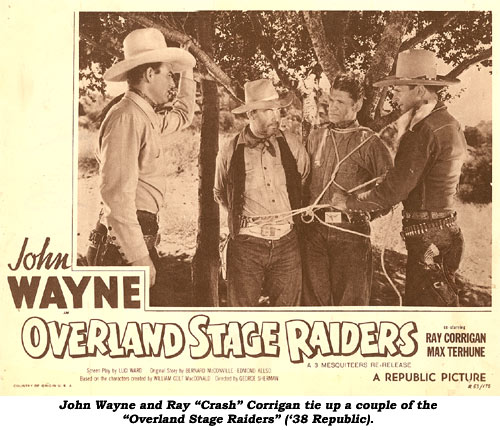

“OVERLAND STAGE RAIDERS” (‘38 Republic) Although the railroad and its coming is often a focal point in B-westerns, actual trains are seldom seen. (Cost?) This is one of the few to make full use of a horse/train chase/shootout action sequence—and it’s a rouser! As part owners of an airport, the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) convince the owner of a gold mine to make his shipments by air rather than stagecoach, as the coaches have been robbed over and over. But when even the airplane is hijacked, the Mesquiteers and airline co-owners are given 24 hours to recover the stolen gold. “OVERLAND STAGE RAIDERS” (‘38 Republic) Although the railroad and its coming is often a focal point in B-westerns, actual trains are seldom seen. (Cost?) This is one of the few to make full use of a horse/train chase/shootout action sequence—and it’s a rouser! As part owners of an airport, the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) convince the owner of a gold mine to make his shipments by air rather than stagecoach, as the coaches have been robbed over and over. But when even the airplane is hijacked, the Mesquiteers and airline co-owners are given 24 hours to recover the stolen gold.

“SANTA FE STAMPEDE” (‘38 Republic) The action pace never lets up as William Farnum and his daughter strike gold and send for their friends The 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) to help out. Crooked mayor LeRoy Mason and his cohorts attempt to get the mine, eventually ambushing and killing Farnum and his younger daughter in a vicious wagon wreck. The crooks accuse Wayne of the murder, but with Corrigan and Terhune he fights to clear his name. “SANTA FE STAMPEDE” (‘38 Republic) The action pace never lets up as William Farnum and his daughter strike gold and send for their friends The 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) to help out. Crooked mayor LeRoy Mason and his cohorts attempt to get the mine, eventually ambushing and killing Farnum and his younger daughter in a vicious wagon wreck. The crooks accuse Wayne of the murder, but with Corrigan and Terhune he fights to clear his name.

“RED RIVER RANGE” (‘38 Republic) Continuous action as modern day truck rustlers use a dude ranch to disguise their thieving activities until the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) intervene on behalf of Lorna Gray (later Adrian Booth), her father and the Cattleman’s Association. Kirby Grant made his debut in this western, even getting to warble a few notes. He later starred in his own series at Universal, then as a mountie for Monogram and finally reached immortality as TV’s “Sky King”. “RED RIVER RANGE” (‘38 Republic) Continuous action as modern day truck rustlers use a dude ranch to disguise their thieving activities until the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) intervene on behalf of Lorna Gray (later Adrian Booth), her father and the Cattleman’s Association. Kirby Grant made his debut in this western, even getting to warble a few notes. He later starred in his own series at Universal, then as a mountie for Monogram and finally reached immortality as TV’s “Sky King”.

“NIGHT RIDERS” (‘39 Republic) To oppose forged Spanish land grants of a phony Don, the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) become the white hooded, night riding Los Capaqueros. Tom Tyler (later a Mesquiteer himself) is one of the outlaws and Kermit Maynard is the sheriff. Remade as “Arizona Terrors” (‘42) with Don Barry. “NIGHT RIDERS” (‘39 Republic) To oppose forged Spanish land grants of a phony Don, the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) become the white hooded, night riding Los Capaqueros. Tom Tyler (later a Mesquiteer himself) is one of the outlaws and Kermit Maynard is the sheriff. Remade as “Arizona Terrors” (‘42) with Don Barry.

“THREE TEXAS STEERS” (‘39 Republic) The 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) ride to the aid of a girl whose circus is being sabotaged by her business manager in order to force her to sell her ranch cheaply as the ranch is valuable because the state wants to build a dam on the property. Corrigan plays a dual role—he also appears as a circus gorilla! Throw a comical trotting horse race into the mix and you have one of the more offbeat and entertaining Mesquiteer adventures. This was Terhune’s last as a Mesquiteer. “THREE TEXAS STEERS” (‘39 Republic) The 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Terhune) ride to the aid of a girl whose circus is being sabotaged by her business manager in order to force her to sell her ranch cheaply as the ranch is valuable because the state wants to build a dam on the property. Corrigan plays a dual role—he also appears as a circus gorilla! Throw a comical trotting horse race into the mix and you have one of the more offbeat and entertaining Mesquiteer adventures. This was Terhune’s last as a Mesquiteer.

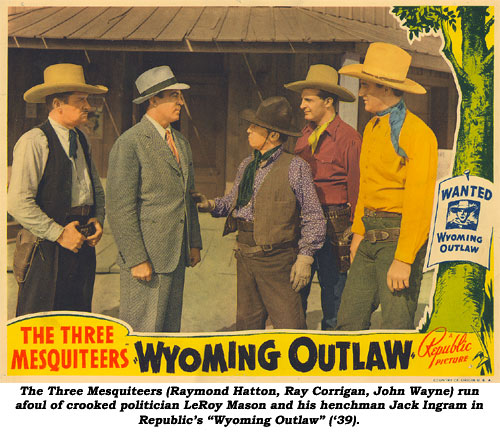

“WYOMING OUTLAW” (‘39 Republic) The most socially relevant film the 3 Mesquiteers made. The contemporary western story of a jobs-for-sale relief racket and the siege of a mountain man trapped by a posse in northwest Wyoming was loosely based on true reports. The Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Raymond Hatton) take a back seat in this excellent little film dominated by Don Barry’s meaty performance of a put-upon-dust-bowl rancher who only poaches cattle or deer from a game preserve to feed his family but lands in trouble when he runs afoul of crooked politicians. Hatton took over third spot in the Mesquiteers from Terhune who was moving over to Monogram’s Range Busters. “WYOMING OUTLAW” (‘39 Republic) The most socially relevant film the 3 Mesquiteers made. The contemporary western story of a jobs-for-sale relief racket and the siege of a mountain man trapped by a posse in northwest Wyoming was loosely based on true reports. The Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Raymond Hatton) take a back seat in this excellent little film dominated by Don Barry’s meaty performance of a put-upon-dust-bowl rancher who only poaches cattle or deer from a game preserve to feed his family but lands in trouble when he runs afoul of crooked politicians. Hatton took over third spot in the Mesquiteers from Terhune who was moving over to Monogram’s Range Busters.

“NEW FRONTIER” (‘39 Republic) Eddy Waller founds the community of New Hope, but the Valley is condemned by the state to build a dam to supply water to the neighboring area. With the aid of the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Hatton), Waller and the settlers fight back against ruthless dam builders and swindlers. Retitled “Frontier Horizon” for TV to avoid confusion with Wayne’s ‘35 film of the same name. This was both Wayne and Corrigan’s exit from the popular Three Mesquiteers series. Corrigan started up the Range Busters at Monogram in the mold of the Mesquiteers, but without taking a back seat to Livingston or Wayne—now he was the lead. Wayne, of course, quickly became one of the biggest movie stars in history. “NEW FRONTIER” (‘39 Republic) Eddy Waller founds the community of New Hope, but the Valley is condemned by the state to build a dam to supply water to the neighboring area. With the aid of the 3 Mesquiteers (Wayne, Corrigan, Hatton), Waller and the settlers fight back against ruthless dam builders and swindlers. Retitled “Frontier Horizon” for TV to avoid confusion with Wayne’s ‘35 film of the same name. This was both Wayne and Corrigan’s exit from the popular Three Mesquiteers series. Corrigan started up the Range Busters at Monogram in the mold of the Mesquiteers, but without taking a back seat to Livingston or Wayne—now he was the lead. Wayne, of course, quickly became one of the biggest movie stars in history.

top of page |