|

|

WAYNE MORRIS WAYNE MORRIS

Ratings: Zero to 4 Stars.

Born in 1914 in L.A., Wayne Morris was a name to reckon with at Warner Bros. before WWII with a string of successes that include “Kid Galahad”, “Men are Such Fools”, “Brother Rat”, “Return of Dr. X”, “Flight Angels” and “Smiling Ghost”. During WWII, flight lieutenant Morris flew F6F Hellcats off the U.S.S. Essex in the South Pacific where he became an American ace, credited with seven confirmed (and one probable) in action over Wake, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. He flew 57 missions and was awarded three Distinguished Flying Crosses and two Air medals. Released from the service in ‘45, he picked up where he left off at WB, but now in second lead position to Dane Clark, Ronald Reagan and Gary Cooper in films such as “Task Force” and “Deep Valley”. Having gained a bit of weight, the ‘50s saw him at WB as well as freelancing at Columbia and U.A. and eventually starring at Monogram/Allied Artists in what many regard as B-westerns’ “last gasp”.

VALLEY OF THE GIANTS (‘38 Warner Bros.) Strictly by the numbers timber pirates tale with every logging film cliché ever seen. Even with Technicolor and a bigger budget, it’s nothing more than a routine B-logger. Filming around Eureka and Orik, CA, amongst the gorgeous redwood forests, and a spectacular logging train/bridge crash sequence gives this typical-of-the-period Warner Bros. film (some drama, some romance, a big barroom-brawl, a few light moments from WB standbys Alan Hale and Frank McHugh) its only interest. Will Wayne Morris pay off his $50,000 note within the six week period? Can he cut enough timber even with all the roadblocks badguy Charles Bickford throws in his way? Will bad girl Claire Trevor reform for the love of a good man like Morris? Will Trevor’s partner, Jack LaRue, who’s protected and loved her for years give her up to Morris? Will Warner Bros. ever cast Alan Hale in something other than the brash but loveable hero’s friend? Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. No. VALLEY OF THE GIANTS (‘38 Warner Bros.) Strictly by the numbers timber pirates tale with every logging film cliché ever seen. Even with Technicolor and a bigger budget, it’s nothing more than a routine B-logger. Filming around Eureka and Orik, CA, amongst the gorgeous redwood forests, and a spectacular logging train/bridge crash sequence gives this typical-of-the-period Warner Bros. film (some drama, some romance, a big barroom-brawl, a few light moments from WB standbys Alan Hale and Frank McHugh) its only interest. Will Wayne Morris pay off his $50,000 note within the six week period? Can he cut enough timber even with all the roadblocks badguy Charles Bickford throws in his way? Will bad girl Claire Trevor reform for the love of a good man like Morris? Will Trevor’s partner, Jack LaRue, who’s protected and loved her for years give her up to Morris? Will Warner Bros. ever cast Alan Hale in something other than the brash but loveable hero’s friend? Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. No.

BAD MEN OF MISSOURI (‘41 Warner Bros.) Highly distorted tale of the Younger Brothers (Dennis Morgan, Wayne Morris, Arthur Kennedy) who return home after the Civil War to find northern carpetbaggers have pillaged their land, killed their father and taken charge of everything. With Jesse James (Alan Baxter) in tow, the three likeable brothers take up the outlaw trail, stymieing carpetbagger Victor Jory, his comic clerk Walter Catlett (whose antics are overplayed) and strong arm man Howard de Silva. Even a little romance is thrown in with Jane Wyman as Kennedy’s girl. It’s the usual western glorified-whitewash-of-facts, even to having Irish tenor Morgan sing “Nellie Gray”, but so what, it all adds up to exciting entertainment. The Civil War battle scenes at the start were excerpted from D. W. Griffith’s silent classic, “The Birth of a Nation”, scenes that were reused in many another Civil War sound epic. BAD MEN OF MISSOURI (‘41 Warner Bros.) Highly distorted tale of the Younger Brothers (Dennis Morgan, Wayne Morris, Arthur Kennedy) who return home after the Civil War to find northern carpetbaggers have pillaged their land, killed their father and taken charge of everything. With Jesse James (Alan Baxter) in tow, the three likeable brothers take up the outlaw trail, stymieing carpetbagger Victor Jory, his comic clerk Walter Catlett (whose antics are overplayed) and strong arm man Howard de Silva. Even a little romance is thrown in with Jane Wyman as Kennedy’s girl. It’s the usual western glorified-whitewash-of-facts, even to having Irish tenor Morgan sing “Nellie Gray”, but so what, it all adds up to exciting entertainment. The Civil War battle scenes at the start were excerpted from D. W. Griffith’s silent classic, “The Birth of a Nation”, scenes that were reused in many another Civil War sound epic.

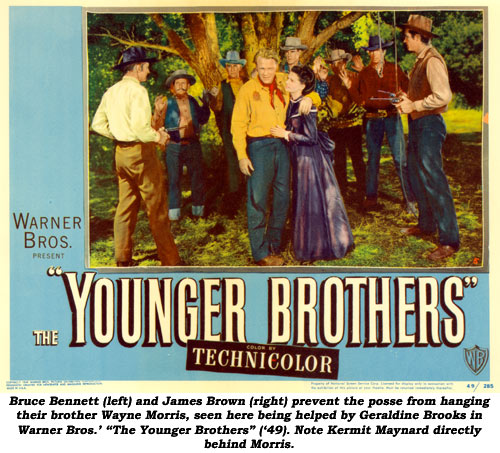

YOUNGER BROTHERS (‘49 Warner Bros.) Strictly revisionist outlaw history that whitewashes the Younger Brothers, here played by Wayne Morris as Cole (he’d been Bob Younger in “Bad Men of Missouri”), Bruce Bennett as Jim, James Brown as Bob and Robert Hutton as Johnny. Awaiting a pardon, the harmless fun-loving boys are forced back on the run by vicious ex-Pinkerton man Fred Clark who carries a grudge against them. Trying to stay out of trouble for two weeks to keep their freedom is tough for these boys who are also put upon to return to their outlaw ways by Janis Paige (and her right hand man Tom Tyler in a meaty role), outlaw leader of her dead brother’s gang. YOUNGER BROTHERS (‘49 Warner Bros.) Strictly revisionist outlaw history that whitewashes the Younger Brothers, here played by Wayne Morris as Cole (he’d been Bob Younger in “Bad Men of Missouri”), Bruce Bennett as Jim, James Brown as Bob and Robert Hutton as Johnny. Awaiting a pardon, the harmless fun-loving boys are forced back on the run by vicious ex-Pinkerton man Fred Clark who carries a grudge against them. Trying to stay out of trouble for two weeks to keep their freedom is tough for these boys who are also put upon to return to their outlaw ways by Janis Paige (and her right hand man Tom Tyler in a meaty role), outlaw leader of her dead brother’s gang.

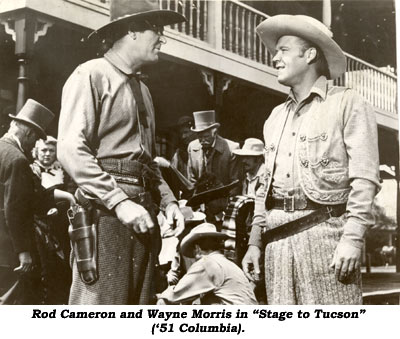

STAGE TO TUCSON (‘51 Columbia) Exciting Republic alumni Bob Williams story enlivened by Charles Lawton Jr.’s action packed Lone Pine color photography has rebel sympathizers stealing Butterfield stages in Arizona just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. Exactly the type of script Williams wrote for “Rocky” Lane and Monte Hale at Republic. Rod Cameron, a Union agent sent to investigate, enlists the aid of stage driver Wayne Morris while they bicker over the affections of Kay Buckley. The “other woman” is Sally Eilers, the former Mrs. Hoot Gibson, now a little long in the tooth, but she was then married to producer Harry Joe Brown. Sleep with the boss and you’ll get the part every time. Watch for James Griffith (back to the camera the whole scene) as Abraham Lincoln. STAGE TO TUCSON (‘51 Columbia) Exciting Republic alumni Bob Williams story enlivened by Charles Lawton Jr.’s action packed Lone Pine color photography has rebel sympathizers stealing Butterfield stages in Arizona just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War. Exactly the type of script Williams wrote for “Rocky” Lane and Monte Hale at Republic. Rod Cameron, a Union agent sent to investigate, enlists the aid of stage driver Wayne Morris while they bicker over the affections of Kay Buckley. The “other woman” is Sally Eilers, the former Mrs. Hoot Gibson, now a little long in the tooth, but she was then married to producer Harry Joe Brown. Sleep with the boss and you’ll get the part every time. Watch for James Griffith (back to the camera the whole scene) as Abraham Lincoln.

SIERRA PASSAGE (‘51 Monogram) Off beat premise with fewer than usual clichés is compelling despite its production disappointments. When he’s a youngster, Morris’ father (Jim Bannon) is robbed and killed by three outlaws including lustily laughing Alan Hale Jr.. Orphaned, Morris is raised by a Wild West Minstrel showman (Lloyd Corrigan) and his trick-shot artist (Roland Winters). Morris grows up to use the spectacular gun skills he’s learned from them to tour the west, always searching for the trio of killers with nothing but revenge on his mind. SIERRA PASSAGE (‘51 Monogram) Off beat premise with fewer than usual clichés is compelling despite its production disappointments. When he’s a youngster, Morris’ father (Jim Bannon) is robbed and killed by three outlaws including lustily laughing Alan Hale Jr.. Orphaned, Morris is raised by a Wild West Minstrel showman (Lloyd Corrigan) and his trick-shot artist (Roland Winters). Morris grows up to use the spectacular gun skills he’s learned from them to tour the west, always searching for the trio of killers with nothing but revenge on his mind.

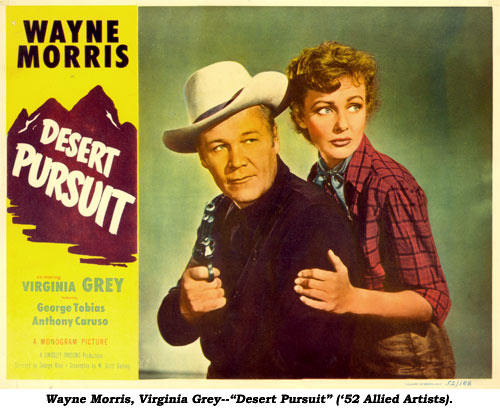

DESERT PURSUIT (‘52 Allied Artists) It’s a hot, dry, sandy trek as three renegade Arabs on camels (Anthony Caruso, John Doucette , George Tobias) pursue Morris, Virginia Grey and the gold across the deserts and rocks of Lone Pine (standing in for nearby Death Valley). Somewhat original concept has a Christmas message to it. DESERT PURSUIT (‘52 Allied Artists) It’s a hot, dry, sandy trek as three renegade Arabs on camels (Anthony Caruso, John Doucette , George Tobias) pursue Morris, Virginia Grey and the gold across the deserts and rocks of Lone Pine (standing in for nearby Death Valley). Somewhat original concept has a Christmas message to it.

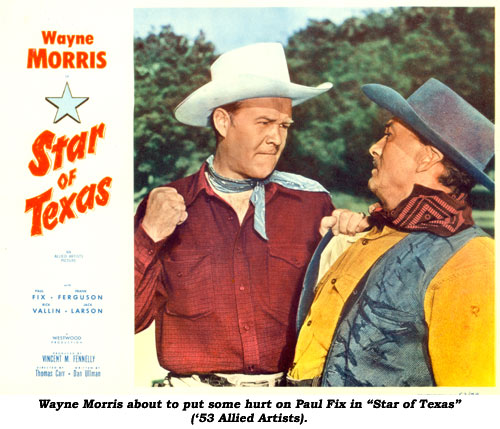

STAR OF TEXAS (‘53 Allied Artists) Veteran director Thomas Carr elected to film this passable entry in semi-documentary style with a narrator describing much of the action. The idea germ for this movie began in ‘45 with Tex Ritter/Dave O’Brien’s “Flaming Bullets”. A gang breaks wanted outlaws out of jail then kills them to collect the reward. The idea was recycled in ‘51 with Whip Wilson’s “Wanted Dead Or Alive”. “Star of Texas” solidifies the idea with Ranger Morris joining the gang to flush out the mystery leader while his pal (Rick Vallin) watches from the sidelines. “Last of the Badmen” (‘57) w/George Montgomery and “Gunfight at Comanche Creek” (‘63) w/ Audie Murphy are virtually the same script (but oddly list different screenwriters!) STAR OF TEXAS (‘53 Allied Artists) Veteran director Thomas Carr elected to film this passable entry in semi-documentary style with a narrator describing much of the action. The idea germ for this movie began in ‘45 with Tex Ritter/Dave O’Brien’s “Flaming Bullets”. A gang breaks wanted outlaws out of jail then kills them to collect the reward. The idea was recycled in ‘51 with Whip Wilson’s “Wanted Dead Or Alive”. “Star of Texas” solidifies the idea with Ranger Morris joining the gang to flush out the mystery leader while his pal (Rick Vallin) watches from the sidelines. “Last of the Badmen” (‘57) w/George Montgomery and “Gunfight at Comanche Creek” (‘63) w/ Audie Murphy are virtually the same script (but oddly list different screenwriters!)

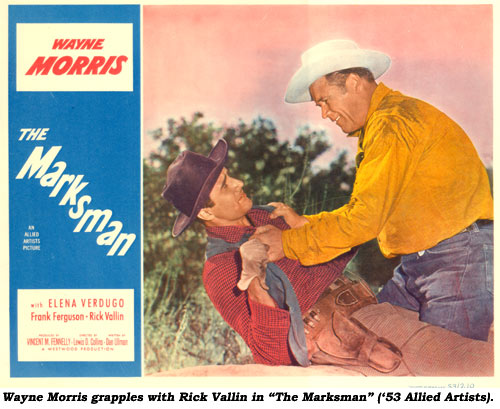

THE MARKSMAN (‘53 Allied Artists) Burdened by too much talk, this is the weakest of Morris’ B-westerns as he plays a roving U. S. Marshal naive on his detective work but an expert sharpshooter. Seeking rustlers who killed another Marshal and disguised as a prospector, Wayne’s inexperience nearly gets him killed. Would have made a good half hour TV episode, but stretched to feature length, there’s too much padding involving a lady western novelist (Elena Verdugo). THE MARKSMAN (‘53 Allied Artists) Burdened by too much talk, this is the weakest of Morris’ B-westerns as he plays a roving U. S. Marshal naive on his detective work but an expert sharpshooter. Seeking rustlers who killed another Marshal and disguised as a prospector, Wayne’s inexperience nearly gets him killed. Would have made a good half hour TV episode, but stretched to feature length, there’s too much padding involving a lady western novelist (Elena Verdugo).

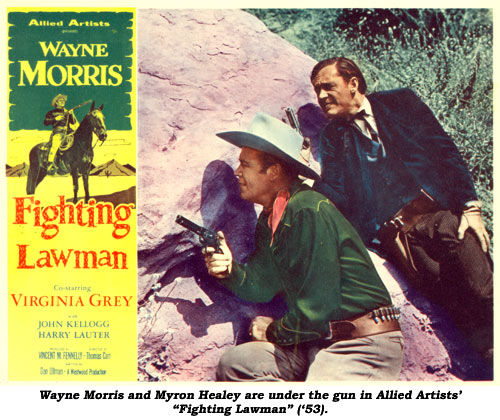

FIGHTING LAWMAN (‘53 Allied Artists) Marshal Morris goes after three men who robbed a bank three years ago in Flagstaff (John Kellogg, Harry Lauter, John Pickard). Now living under assumed names in Prescott, it’s the greedy sister (Virginia Grey) of a fourth bandit, now dead, who proves their undoing. Bit different in plot, but still only a mediocre affair. FIGHTING LAWMAN (‘53 Allied Artists) Marshal Morris goes after three men who robbed a bank three years ago in Flagstaff (John Kellogg, Harry Lauter, John Pickard). Now living under assumed names in Prescott, it’s the greedy sister (Virginia Grey) of a fourth bandit, now dead, who proves their undoing. Bit different in plot, but still only a mediocre affair.

TEXAS BADMAN (‘53 Allied Artists) Not available for viewing.

THE DESPERADO (‘54 Allied Artists) Leaving his girl (Beverly Garland) behind, Jimmy Lydon and his friend Rayford Barnes flee the carpetbagger rule of oppressive Nestor Paiva. On the trail they meet fugitive gunfighter Morris who befriends Lydon after Barnes tries to kill Morris for a reward. Returning to town, the treacherous Barnes kills Paiva and another “Bluebelly” carpetbagger, making it appear Lydon did the deed. On the run, Lydon rides the owlhoot trail with Morris until he’s captured and returned for trial. In court, the traitorous Barnes lies under oath, blaming Lydon, until Morris interrupts the trial at gunpoint to get Lydon off the hook and put Barnes under the noose. Lee Van Cleef is seen in a dual role. Different in approach during the final days of the B-western, but a bit drawn out at 80 minutes, plus Lydon is no horseman and is slow on the draw when he’s supposed to be fast, and Morris looks just plain worn out and overweight. Remade in ‘58 as “Cole Younger, Gunfighter” with Frank Lovejoy. THE DESPERADO (‘54 Allied Artists) Leaving his girl (Beverly Garland) behind, Jimmy Lydon and his friend Rayford Barnes flee the carpetbagger rule of oppressive Nestor Paiva. On the trail they meet fugitive gunfighter Morris who befriends Lydon after Barnes tries to kill Morris for a reward. Returning to town, the treacherous Barnes kills Paiva and another “Bluebelly” carpetbagger, making it appear Lydon did the deed. On the run, Lydon rides the owlhoot trail with Morris until he’s captured and returned for trial. In court, the traitorous Barnes lies under oath, blaming Lydon, until Morris interrupts the trial at gunpoint to get Lydon off the hook and put Barnes under the noose. Lee Van Cleef is seen in a dual role. Different in approach during the final days of the B-western, but a bit drawn out at 80 minutes, plus Lydon is no horseman and is slow on the draw when he’s supposed to be fast, and Morris looks just plain worn out and overweight. Remade in ‘58 as “Cole Younger, Gunfighter” with Frank Lovejoy.

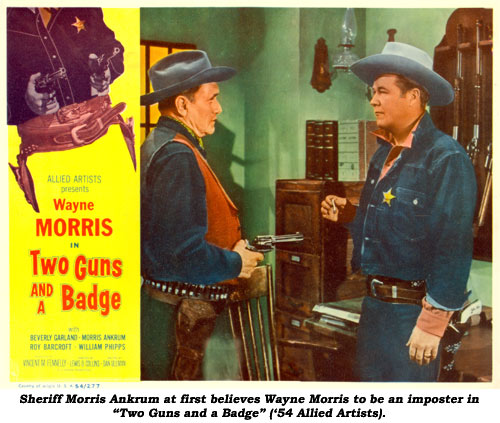

TWO GUNS AND A BADGE (‘54 Allied Artists) Regarded by many film historians as the last series B-western ever made and released (September ‘54), an argument could be made against that theory if one factors in the Guy Madison Wild Bill Hickok Allied Artists pictures released clear into ‘55. Certainly a “series”, but all 16 of those were comprised of two TV episodes strung together into feature form, so many purists dismiss them. Then too, low budget B-star Johnny Carpenter released “Outlaw Treasure” in May ‘55 and “I Killed Wild Bill Hickok” in June ‘56. Strong arguments could be made both ways for Carpenter who had been turning out about one B-western a year since ‘51. But does that qualify as a series? Again, purists will argue no, as they will also argue against the many one-off or non-series entries, but decidedly B-westerns, made throughout the ‘50s starring Jim Davis, Bill Williams, John Bromfield, Buster Crabbe, James Craig, etc. Did the B-western so prevalent throughout the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s truly end with “Two Guns and a Badge” starring Wayne Morris or did it just metamorphosize into the slightly bigger budgets of Rod Cameron, George Montgomery, Audie Murphy, Sterling Hayden, etc.? Their movies certainly couldn’t be called A-westerns on a scope with those of John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Robert Taylor, Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea. But, as purists will argue, they aren’t true series B-westerns either. Still and yet, did the series B-western simply cease to exist on the theatre screen only to find a new home on TV in a continuation of former filmic heroes like Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Hopalong Cassidy, Cisco Kid—and finding new heroes such as Wild Bill Hickok, Kit Carson, Steve Donovan, Wyatt Earp, Cheyenne, Sugarfoot, Bronco. Certainly series westerns. Certainly not A-westerns. Semantics. Why must we “label” our westerns B, A or TV? The film world and viewers alike seem to have an unquenchable thirst to pigeon hole movies into this category or that. But look at it this way, if TV hadn’t come along and Clint Walker and Warner Bros. would have released those “Cheyenne” films in theatres, wouldn’t we call them b/w, one-hour, series B-westerns and eaten them up week after week (just as we did on television)? But, appropriately, for purists, “Two Guns and a Badge”, is the “final” series B-western, a story of rustlers and ranchers with a mystery villain who turns out to be not who you think it is. In other words, it ain’t Roy Barcroft! Morris poses as a lawman (whom he found dead on the trail and appropriated his distinctive guns) to help Sheriff Morris Ankrum clean up the town of the rustlers. TWO GUNS AND A BADGE (‘54 Allied Artists) Regarded by many film historians as the last series B-western ever made and released (September ‘54), an argument could be made against that theory if one factors in the Guy Madison Wild Bill Hickok Allied Artists pictures released clear into ‘55. Certainly a “series”, but all 16 of those were comprised of two TV episodes strung together into feature form, so many purists dismiss them. Then too, low budget B-star Johnny Carpenter released “Outlaw Treasure” in May ‘55 and “I Killed Wild Bill Hickok” in June ‘56. Strong arguments could be made both ways for Carpenter who had been turning out about one B-western a year since ‘51. But does that qualify as a series? Again, purists will argue no, as they will also argue against the many one-off or non-series entries, but decidedly B-westerns, made throughout the ‘50s starring Jim Davis, Bill Williams, John Bromfield, Buster Crabbe, James Craig, etc. Did the B-western so prevalent throughout the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s truly end with “Two Guns and a Badge” starring Wayne Morris or did it just metamorphosize into the slightly bigger budgets of Rod Cameron, George Montgomery, Audie Murphy, Sterling Hayden, etc.? Their movies certainly couldn’t be called A-westerns on a scope with those of John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Robert Taylor, Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea. But, as purists will argue, they aren’t true series B-westerns either. Still and yet, did the series B-western simply cease to exist on the theatre screen only to find a new home on TV in a continuation of former filmic heroes like Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Hopalong Cassidy, Cisco Kid—and finding new heroes such as Wild Bill Hickok, Kit Carson, Steve Donovan, Wyatt Earp, Cheyenne, Sugarfoot, Bronco. Certainly series westerns. Certainly not A-westerns. Semantics. Why must we “label” our westerns B, A or TV? The film world and viewers alike seem to have an unquenchable thirst to pigeon hole movies into this category or that. But look at it this way, if TV hadn’t come along and Clint Walker and Warner Bros. would have released those “Cheyenne” films in theatres, wouldn’t we call them b/w, one-hour, series B-westerns and eaten them up week after week (just as we did on television)? But, appropriately, for purists, “Two Guns and a Badge”, is the “final” series B-western, a story of rustlers and ranchers with a mystery villain who turns out to be not who you think it is. In other words, it ain’t Roy Barcroft! Morris poses as a lawman (whom he found dead on the trail and appropriated his distinctive guns) to help Sheriff Morris Ankrum clean up the town of the rustlers.

top of page |