CHARLIE KING

Charles King is, without a doubt, the preeminent badman of ‘30s and ‘40s B-westerns. In the early years, Charlie alternated between wearing a thick black mustache or being clean shaven. It was quite obvious he was always fighting the ‘battle of the bulge’ but still maintained a good figure until the late ‘30s when he must have decided to ‘let it all hang out’. His paunchy pot-belly, ever growing mustache (which flowered to full old-west droopiness in many PRC titles), and often baggy-pants western garb endeared him to several generations of front row kids. In his nearly 300 westerns Charlie had the opportunity to play every type of villain from suave banker or saloon owner to the nastiest, black-hearted, dog-kicker of them all. Charles Lafayette King Jr. was born February 21, 1895, in Hillsboro, TX, the son of a Kentucky born physician. His father wanted Charles to follow in his footsteps but Charlie chose acting instead. At age 20 (or possibly younger) Charlie was in Hollywood with his earliest purported work as an extra in “Birth of a Nation” (1915). His first recorded film work was as a bartender in the 1921 comedy “A Motion To Adjourn” with Roy Stewart. He supported William Russell the same year in “Singing River”. “The Price of Youth” and “The Black Bag” followed in 1922. One of his earliest, if not his first, western roles was opposite Lester Cuneo in “Hearts of the West” (‘25). From there he was seen menacing Fred Humes and Bill Cody in silent oaters. But before Charlie really became established in westerns he had a run at being a comedian in Universal’s popular Mike and Ike two-reel comedy shorts of the late ‘20s. Researcher Ken Weiss found this notice in the September 1928 UNIVERSAL WEEKLY, a studio in-house publication.

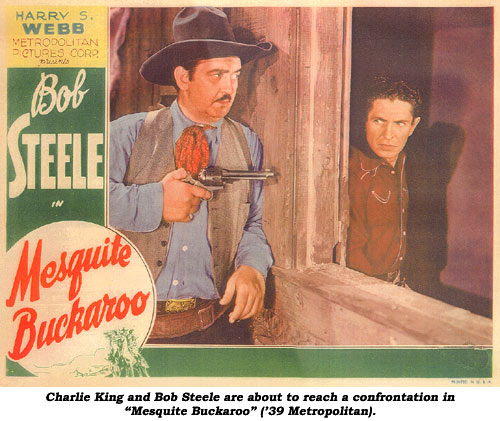

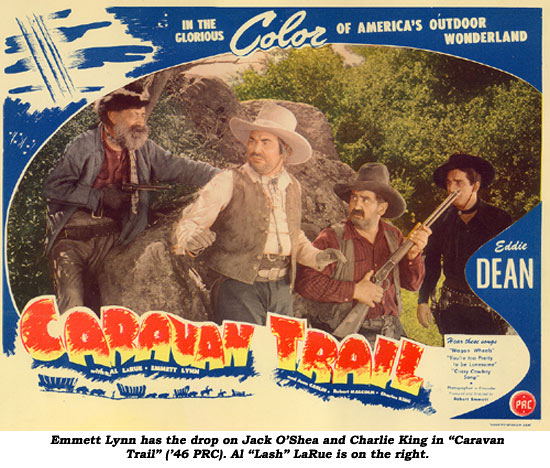

Charlie’s comedic flair was often demonstrated in westerns—especially the Dave O’Brien/Tex Ritter PRC series (in particular “Enemy of the Law”) and “Caravan Trail” with Eddie Dean and Al (Lash) LaRue (“Rabbits, rabbits, rabbits!”).  With the advent of sound, Charlie found himself solidly ensconced and well-received in hordes of B-westerns opposite Ken Maynard, Buck Jones, Bob Steele, Tim McCoy, Rex Bell, Hoot Gibson, Gene Autry, Kermit Maynard, Tom Tyler and others. His barroom brawls with, first, Bob Steele then Tex Ritter became legendary screen battles we all eagerly anticipated.

Although all the studios employed him, PRC and Monogram kept Charlie the busiest in the ‘40s in feature after feature, daunting the likes of Buster Crabbe, Lee Powell, James Newill, Dave O’Brien, George Houston, Johnny Mack Brown, the Rough Riders, Tom Keene, Lash LaRue, Trail Blazers, Range Busters and others.

Charlie had found work in serials since “What Happened to Jane” in 1926 and continued to do so with “Congo Bill” (‘48), “Adventures of Sir Galahad” (‘49) (again displaying his true comic talent) and “Bruce Gentry” (‘49).

Despondent and out of work, Charlie attempted suicide on February 15, 1951, only days before his 56th birthday, according to an L.A. EVENING HERALD AND EXPRESS 2/16/51 article (Thanx to G. D. Hamann.) Charlie “gazed upon the peaceful scene of his family gathered in the living room at 539 North Arden Blvd. watching television. Tears coursed down his cheeks as he entered the room and announced, ‘I love you all—goodbye!’ Then he stalked dramatically out and, a few moments later, the family heard a (gunshot) report and rushed into the bathroom to discover Charlie had shot himself in the chest with his son’s .22 caliber rifle. He was too rugged for that, however. Police said the bullet coursed around his ribs and out his back and that his injury was not critical. No reason was given (to police) for his act.” Following his recovery and during his final years, Charlie appeared as an extra on early episodes of “Gunsmoke” (watch for him right behind James Arness as a courtroom observer in “Custer”, drinking a beer in the barroom in “Man Who Would Be Marshal” and “Jealousy”, sitting in a chair in “Liar From Blackhawk”, playing cards in “Uncle Oliver”, etc.) It’s often been said King died while playing a corpse on the James Arness series, or minutes thereafter. However, this is doubtless the stuff of which western “urban legends” are born as I’ve personally never seen a “Gunsmoke” where King played a corpse. The other fact that makes this unlikely is the time of his death on May 7, 1957—7:45pm. Not that they couldn’t have been filming this late, it’s just more unlikely. Actually, Charlie died at 62 of a hepatic coma brought on by cirrhosis and chronic alcoholism at John Wesley County Hospital. At the time he was divorced and living at 4914 Bellaire Ave. in N. Hollywood. (His son, Charles S. King, was killed in the ‘80s at an early age when he surprised a man burglarizing his apartment.) If only Charlie had lived to realize he was the heavy we loved to hate, I think he would have been pleased.

|