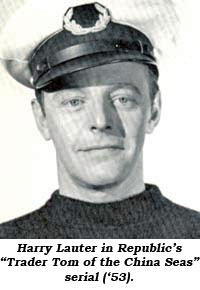

HARRY LAUTER HARRY LAUTER

Harry Lauter started out his quarter century in film playing juvenile leads in non westerns in 1947. By 1949 he was doing the same in the westerns of Allan “Rocky” Lane, Monte Hale, Rex Allen and TV’s “Lone Ranger”. But Harry soon found his niche playing bushwhackers, rustlers and just plain no goods in several B-westerns but primarily on TV in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Gene Autry’s Flying-A Productions was his most frequent employer with every series Gene produced.

Herman Arthur Lauter was born June 19, 1914, in White Plains, New York. His grandparents were circus people, the world famous trapeze act, The Flying Lauters. Harry’s father was also involved in the act as well as being a graphic artist, and his uncle was one of the foremost church stained-glass window artists in the country. His mother, who died when Harry was four, wrote for the LITERARY DIGEST. His parents moved to Colorado when Harry was quite young which is where he learned to ride. They later moved to San Diego. When Harry was 13 he established California State Junior records in the 100 yard and 220 yard free style swimming sprints. In San Diego Harry attended grammar school and San Diego High. While still in high school, he began working at radio station KGB as an announcer and general handyman. Whenever time would permit, he appeared in plays at the Globe Theatre in Balboa Park. This theatre experience convinced Harry he wanted an acting career and it led to his joining the Elitch Garden Theatre Group in Denver, CO, one of the oldest stock companies in the country.

Harry’s first wife was named Dorothy; they had a son named Bill. In 1946 Harry married Barbara Ayres whom he met while appearing at Elitch Gardens. They had a daughter, Brooke. The couple were divorced in 1980. Harry married Doris Gilbert in 1990. Harry soon went to New York, where he worked in several radio dramas, and to New England for summer stock. He toured the country with Lillian Gish in “The Story of Mary Suratt” in 1947 and was doing “The Voice of the Turtle” at Martha’s Vineyard in Maine when Hollywood producer Frank Seltzer spotted him.

Drafted for the duration of WWII, upon his discharge 20th Century Fox brought him out to California but never used him so he asked for a release. It was then he began to work, with his first film being “Hit Parade of 1947” in 1946. After bit roles in a few other films, Harry asked himself what movies would always be doing. westerns. Being a good rider and with television coming on, westerns are what he concentrated on. Harry told Tom and Jim Goldrup for their FEATURE PLAYERS Vol. 1, he liked playing heavies, “because every part you do is a challenge. You got to watch yourself that you don’t get into a set character. I used to like to work with makeup, not go overboard on it, but play with a scar, or the character itself. I like to play the heavy because they pretty well leave you alone, unless you go overboard. I love the heavies, and I love the reaction I get from people. ‘Why are you so mean on screen? You’re not a mean guy at all.’ Most of the people I know that played really nasty heavies, Bob Wilke, Mickey Simpson…they are the nicest guys in the world.”

In another interview Harry smiled, “I loved to play villains, especially in horse operas. That’s what I’m best in and what I like most. I can ride anything that moves on four legs and it never bothered me one teeny bit that I didn’t get to wear the white hat or win the girl at the end. When I was a kid I always remembered the varmint better than the hero anyway.” The artist’s blood from his family came through in Harry also. When he worked on location, he’d often spend time in between takes painting the Tetons, the Sierras, the Rockies, the Alabams at Lone Pine. Harry’s widow Doris wrote in 1999, “Harry became an accomplished artist, painting mostly beautiful oil landscapes, with lakes, trees, and mountains. His father, also an artist, was a great influence on him as a child. The Favell Museum of Western Art (in Klamath Falls, Oregon) has one of his landscapes on display in their permanent collection (alongside those of Remington and Russell). Being an artist myself, we met in 1970 at various art functions. He had a gallery in Studio City, California, ‘Lauters Gallery Row,’ and also ran an art show on La Cienega on Sundays. After we married, we had a small gallery in Ojai where we did our paintings. We exhibited together in professional art shows and two-man shows all over the country. He sold everything he painted, and was pleased that his art would be around long after he was gone.”

As the westerns began to fade from view, Harry wound his career with an episode of “How the West Was Won” in ‘79 and concentrated more on artistic endeavors. “It’s been a marvelous business and it’s been very kind to me. I have no regrets over it at all.” Harry attended several western film festivals until his health began to fail. One of the nicest western heavies—one of the best of the badmen—died October 30, 1990, of heart failure at his home in Ojai, CA. Myron Healey remembers, “Harry probably saved my life. We were up at Big Bear for a week’s location shoot with Autry; Harry and I were doing heavies. I’m supposed to ride by a rock, Gene follows and bulldogs me into the lake for a fight in that cold water. Harry has to ride by with Pat Buttram pursuing him—Pat bulldogs him and he succumbs to Pat—on dry ground. Now, I had a bad cold all week—real sick, coughing, no medication. Unbeknownst to me, Harry talked to director George Archainbaud and said, ‘What’s the difference who goes in the water? Let us switch places.’ So we did—If I’d gone in the water I would have come down with pneumonia and possibly died. To this day, I say Harry probably saved my life. He was always good for a laugh—take a bad situation and make it fun.” Chris Alcaide had a similar experience, “Harry was always willing to help another actor. I hurt my back the first day we were shooting…so in fight scenes Harry went out of his way to make sure I didn’t hurt myself further—he did all the hard stuff. Doing a ‘Kit Carson’ episode, Harry told me ‘Never roll your sleeves up ‘cause then you can’t wear armpads, and get a pair of gloves so your hands won’t get ripped up in the dirt.’ He was good at comedy too—just never got the chance.”

|