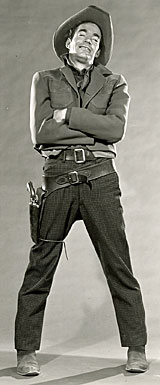

JACK ELAM JACK ELAM

“The heavy today is usually not my kind of guy. In the old days, Rory Calhoun was the hero because he was the hero and I was the heavy because I was the heavy—and nobody cared what my problem was. And I didn’t either. I robbed the bank because I wanted the money. I’ve played all kinds of weirdoes but I’ve never done the quiet, sick type. I never had a problem—other than the fact I was just bad.” In his own words Jack Elam, the man with the off-kilter eye, described the type of heavy that made him one of the top five screen heavies in a career that spanned nearly 50 years with his rich repertoire of badmen, scoundrels, gangsters and loveable bumblers. Even an occasional hero. Jack Elam was born November 13, 1920, in Miami, Arizona, a tiny mining community 100 miles from Phoenix, then grew up in Phoenix. His mother died when Jack was about two and he lived with various families who made him earn at least part of his keep. He remembered picking cotton at six. When Jack was nine he was reunited with his father, a building and loan appraiser who suffered from a serious eye ailment which made it difficult for him to work. He had Jack fill out forms for him at night. When Jack was 12, he, himself, suffered the loss of vision in his left eye when he was involved in a fight at a Boy Scout meeting and was jabbed in the eye with a pencil by another boy. Elam had no control over his wandering eye, “It does whatever the hell it wants,” Jack laughed. But the handicap became an asset when he later turned to movie work. His eyes conveyed villainy as surely as Durante’s nose suggested humor,” Doug Martin wrote. “One eye squinted and the other was open. One pointed one way and the other another. It all seemed malevolent.” As he changed from thugs to humorous characters, so followed the eye to comic situations.

Exempt from WWII military service because of his eye, Jack worked as a civilian for the Navy in Culver City. During his 20s and early 30s, Jack took a position as both auditor and manager of the famed Bel Air Hotel. When the Bel Air sold, Jack proved himself to be a ‘Jack of all Trades’ working as an accountant, purchasing agent, business manager and controller at Hopalong Cassidy Productions. Working as an auditor looking at numbers put a strain on Jack’s good eye. His eye doctor told him to find a new line of work. Because of his contacts in the picture business, he was able to help establish financing for three films (two of which were “High Lonesome” and “The Sundowners”, both ‘50) in exchange for a small role in each. Jack’s big break came in 1949 filming “Rawhide” for director Henry Hathaway. With strong encouragement from star Tyrone Power, Jack played one of the nastiest, most sadistic villains ever on the screen. Power urged Darryl Zanuck to put Elam under contract, which resulted in a seven year contract at 20th Century Fox. Jack was off and running and never stopped being in huge demand until his last film (“Bonanza: Under Attack” for TV) in ‘95…119 movies and 260 television appearances.

Jack’s career falls into three phases—in the ‘50s and ‘60s he was the meanest of screen heavies, that is, with the exception of being on the right side of the law as reformed gunfighter, J. D. Smith, deputy to Marshal Frank Ragan (Larry Ward) for 19 episodes of Warner Bros.’ “The Dakotas” in ‘63. When that series failed, WB put Jack into “Temple Houston” (‘63-‘64) as Jeffrey Hunter’s sidekick, George Taggart, another reformed gunfighter. In the late ‘60s, beginning with “Support Your Local Sheriff” (‘69) starring James Garner, Elam drifted into comedic portrayals, often playing a self parodying western heavy such as Sam Urp on “F-Troop: Dirge of the Scourge” (‘65). The star of “Gunsmoke”, James Arness, said, “He played a rogue kind of guy, but not a real mean heavy, although he could certainly do that. What made him distinctive was the fact he could play unusual characters and he had this marvelous face—it was one of a kind. Also he was a great card player, great at all kinds of gambling. He always took everybody’s money when he was on the set. He was a wonderful guy.” When, as Elam put it, “I grew too old and too fat to jump on a horse,” he grew a long beard and settled into loveable old coot characterizations on “Father Murphy”, “Alias Smith and Jones”, “Paradise” and in “Hawken’s Breed” (‘87), “Big Bad John” (‘90), “Once Upon a Texas Train” (‘88) and “Lucky Luke” (‘95). Pinned down as to his favorite film, it’s “Support Your Local Gunfighter”. King Vidor and Burt Kennedy were directors Elam admired. His work in “Ransom of Red Chief” led to a 1977 daytime Emmy nomination. In 1983 Jack received the Golden Boot Award and in 1994 he was inducted into the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City. Cards were always one of Jack’s passions. An avid poker player and a proponent of Liar’s Poker, the stories about Jack’s gambling are legendary. Another terrific heavy, Gregg Palmer, remembers, “I kept bills in my wallet just for Jack Elam! We always played Liar’s Poker on the lot. He had that one bad eye. Well, I had one bill tucked away just for Jack. I’m over at CBS doing a ‘Gunsmoke’ and Jack’s in there playing Liar’s Poker with Paul “Tiny” Nichols, the first assistant director, and Bob Totten, the director. Jack says to me, ‘Get your money out.’ Now, the crew would always come in and give Jack bills with four numbers (alike) on it or five numbers for Liar’s Poker. So I pulled out my bill and the game went to four fours and five of these. Finally, I got up and said ‘Six sevens.’ There’s only four of us playing. Nichols says, ‘Pass.’ Totten passed. Jack looked at me with that big smile of his and says, ‘Gotcha cowboy.’ I looked at him and said, ‘I called seven sevens.’ I knew I’d only called six. Nichols said, ‘No, you only called six, Gregg.’ Jack said, ‘He called seven sevens!’ I said, ‘How many sevens do you have Paul?’ ‘None.’ Totten? ‘None.” Elam? ‘None.’ So I took the money and said, ‘Thank you, just made it.’ Elam said, ‘Whatcha talkin’ about?’ I said, ‘I called seven sevens you said.’ Elam growls, ‘Lemme see that bill!’ I had seven sevens on this bill. Jack’s eye, from the side, went all the way down to the center and back up again! He says, ‘You got me, didn’t you? You got me.’ Jack was the only one who ever had in his contract at Warner Bros. (on “Temple Houston” and “Dakotas”) the right to gamble on the set. Everybody else they closed down. You couldn’t play Pitch or Hearts or anything like that. But we had the understanding if they called you to the set, you threw your cards in. God love him.”

Will summed up the Jack Elam he knew, “He was the brother I’d never had; my long-lost uncle who once blew into town with gifts and wild tales; my dad who died too soon. I liked Jack straight off, the way I liked his acting. The abiding intelligence and humanity of the man overwhelmed me. Today I see a lot of sensational actors on screen showing off, but where’s the humanity? Jack Elam doesn’t show off. He doesn’t show you anything. He lets you discover it for yourself. Whether he plays the good bad guy or the bad good guy, he has the ability to take us along with him, so we seem to be working things out together.” “I drank scotch and played poker.” That’s what Jack Elam always said he wanted on his tombstone. Jack died at 82, October 20, 2003, of congestive heart failure at his home in Ashland, Oregon, where he’d lived since 1990.

|