|

|

“Brenda Starr, Reporter”

With the possible exception of the DAILY PLANET's Lois Lane, ace reporter Brenda Starr probably logged in more hours on the job than any other female newshound. The fictional Brenda finally hung up her comic strip notepad last year after 70 years of pounding the pavement for stories. With the possible exception of the DAILY PLANET's Lois Lane, ace reporter Brenda Starr probably logged in more hours on the job than any other female newshound. The fictional Brenda finally hung up her comic strip notepad last year after 70 years of pounding the pavement for stories.

Brenda was the brainchild of cartoonist Dalia Messick who created the red-haired reporter in 1940. Female cartoonists were somewhat of a rare breed during this period and as a consequence she altered her first name to Dale to avoid prejudice when submitting her material for consideration. Although finally finding a berth at Chicago Tribune Syndicate, BRENDA STARR was initially relegated to a once a week appearance in the paper’s Sunday comic supplement. The storyline gradually gained a large audience however, and Brenda got her own daily strip in 1945. Soon, she was the best known newswoman in the country.

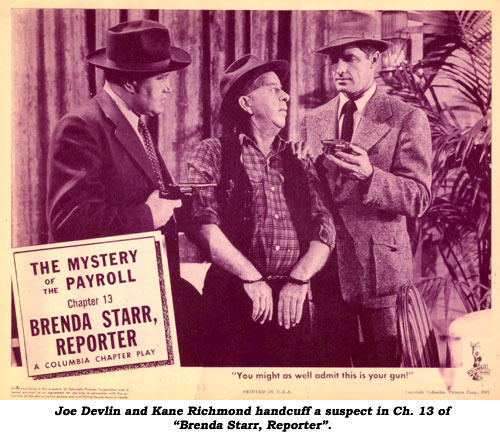

In 1945 Columbia, who often went to the comics for their cliffhanger inspirations, produced the serial “Brenda Starr, Reporter”. For some reason this was put together in 13 chapters, the usual formula calling for either 12 or 15 installments. In 1945 Columbia, who often went to the comics for their cliffhanger inspirations, produced the serial “Brenda Starr, Reporter”. For some reason this was put together in 13 chapters, the usual formula calling for either 12 or 15 installments.

The plot, fashioned by Andy Lamb and the venerable George H. Plympton, was fairly pedestrian and chronicled Brenda’s tenacious attempts tolocate the whereabouts of a stolen payroll. It wasn’t a particularly interesting concept and in actuality it was more of an average cops-and-robbers storyline which just happened to have cliffhangers thrown into the mix rather than the other way around. But it did have one strong ingredient that helped elevate it above what could easily have been a very routine and unremarkable effort. It had Joan Woodbury.

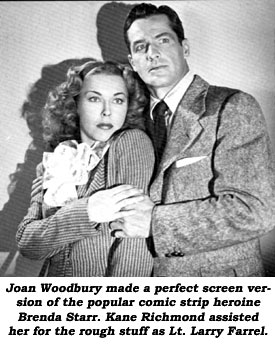

Woodbury (1915-1989) is fondly remembered today as one of the standout players in many programmers and “B” films of the ‘30s and ‘40s. Her Danish, British and Native-American ancestry gave her a uniquely beautiful and somewhat exotic appearance which served her well in being cast in a wide variety of roles. In addition, she was a talented dancer and could play comedy as well as drama, always displaying great energy and a sassy sort of sexuality. Whether featured in westerns or numerous dramatic roles, the camera always loved her. As Brenda she is plucky, resourceful, steadfast, sometimes a bit hair-brained and always a joy to watch. Woodbury (1915-1989) is fondly remembered today as one of the standout players in many programmers and “B” films of the ‘30s and ‘40s. Her Danish, British and Native-American ancestry gave her a uniquely beautiful and somewhat exotic appearance which served her well in being cast in a wide variety of roles. In addition, she was a talented dancer and could play comedy as well as drama, always displaying great energy and a sassy sort of sexuality. Whether featured in westerns or numerous dramatic roles, the camera always loved her. As Brenda she is plucky, resourceful, steadfast, sometimes a bit hair-brained and always a joy to watch.

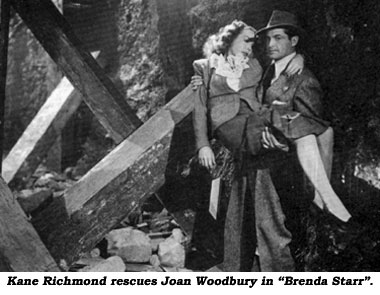

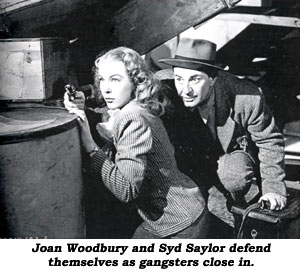

Backing Woodbury up is Kane Richmond as police Lieutenant Larry Farrel. Richmond was a square-jawed and handsome actor who appeared in numerous action films and chapterplays, his most famous in the latter category being the lead in Republic’s “Spy Smasher”, one of the screen’s best remembered serials. He also portrayed The Shadow in a short series of films for Monogram. Here he works well with Woodbury. They have a kind of Nick and Nora Charles relationship with a lot of verbal sparring and wisecracks flowing between them but there’s really not much to his pretty thankless role save for lines like “Gosh, Brenda, I thought you were a goner.” Brenda’s true partner in the action is the lanky, somewhat goofy-looking comedic actor Syd Saylor who had a long career in second banana roles. Here he portrays Chuck Allen, staff photographer on the DAILY BLAZE where he and Brenda work. Woodbury and Saylor establish a comfortable and likable rapport complete with a lot of kidding and humorous asides which, thanks to the writing of Lamb and Plympton, help transcend the usual meat-and-potatoes dialog found in most serials.

In addition, the leads have a good solid supporting cast. The bad guys are represented by such familiar faces as Jack Ingram, Anthony Warde, John Merton, Wheeler Oakman, Cay Forester, Ernie Adams and George Meeker, villains operating in opposing camps as they seek the stolen payroll. Also around for the fun are Joe Devlin as Tim, Farrel’s cop partner and betting rival of Chuck, and the ubiquitous Billy Benedict as Pesky, the office errand boy whose reputation revolves around the fact that he gets everything backwards, a trait that will serve him well in the story’s conclusion. In addition, the leads have a good solid supporting cast. The bad guys are represented by such familiar faces as Jack Ingram, Anthony Warde, John Merton, Wheeler Oakman, Cay Forester, Ernie Adams and George Meeker, villains operating in opposing camps as they seek the stolen payroll. Also around for the fun are Joe Devlin as Tim, Farrel’s cop partner and betting rival of Chuck, and the ubiquitous Billy Benedict as Pesky, the office errand boy whose reputation revolves around the fact that he gets everything backwards, a trait that will serve him well in the story’s conclusion.

“Brenda Star, Reporter” was producer Sam Katzman’s first serial and is far from the most action-filled of chaperplays. The cliffhangers are pretty routine stuff and usually not all that well executed. Brenda nearly gets squashed by a moving packing crate, barely escapes a poison gas attack in the back of a speeding car and is almost buried alive during a mine explosion. But in most of these harrowing instances she survives more by accident and dumb blind luck that any ingenuity or cleverness on her part. One of the refreshing things about her predicaments, however, is that when she does find herself in one of these potentially lethal jams she displays a lot of obvious fear with her big and expressive eyes and her mouth open ready to scream or call for help, something you rarely see in characters in most other serials. But then Woodbury was a good actress, lively and full of vim and vigor, and could always be counted on to give a good performance regardless of the project. As Brenda she brings a sincerity, spontaneity, likeability and three-dimensional quality to the famed reporter which is fun and most satisfying to watch.

Fans and followers of the BRENDA STARR strip—which this reviewer cannot admit to having ever been—are on record as saying the serial bore scant resemblance to the original source material. Perhaps this is so. Serials traditionally played fast and loose with the characters they transferred to the screen. The “Captain America”, “Chick Carter, Detective” and “Lone Ranger” productions are notable examples of this.

Still, her comic strip roots aside, “Brenda Starr” is worth a look if nothing else to see Joan Woodbury in her prime. The actress made only one serial and is on record as stating once was enough for her in the cliffhanger department. Both the choppy and ultra fast shooting schedule and a script as large as a phone book were apparently not to her liking. None of this negative reaction, however, is in any way reflected by her energetic and pleasing performance.

Note: The journey to locate a viewable copy of “Brenda Starr”, long considered lost, was a difficult one which took many years and a great deal of effort to accomplish. Through these efforts a print was eventually pieced together by VCI but chapters three and four both lack video and audio sections.

At the end of Ch. 5 of “Secret Agent X-9” (‘37 Universal), X-9 removes from a bookcase a booby-trapped book which fires a gun. He crumples to the floor. But, in Ch. 6 Pidge warns X-9 as he’s about to remove the book and it’s Pidge who is shot in the shoulder. X-9 never falls to the floor. |

In almost every serial there are men who exhibit outstanding loyalty, dedication, deter-mination, skill and courage far beyond the line of duty. I’m referring, of course, to the master villain’s main henchmen. These are the men the arch fiend depends on to do his dirty work—jobs that involve extreme risk to life and limb, bravery that would beggar the imagination of most of us, and talents that put mere mortals to shame. Among other qualities, the main henchmen had to be fast thinkers, good brawlers, handy with guns, expert at driving cars at high speeds as well as piloting planes and boats, and willing to follow the most impossible and possibly suicidal orders with nary a word of complaint.

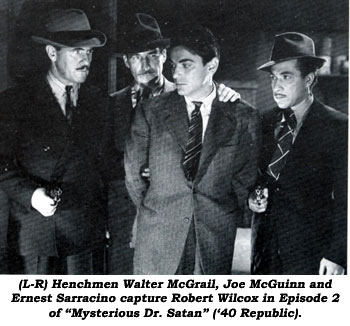

Take, for example, the henchmen of Dr. Satan, in “Mysterious Dr. Satan” (‘40 Republic). He’s after a new remote-controlled airplane being tested by the government. In Ch. 2 he tells two henchmen to get a plane of their own, follow the test plane, board it in mid air, and steal the remote control device. In case that doesn’t work, he orders two other goons to follow the plane by car, be wherever it lands, then steal the unit. The four men accept these assignments as if they were being sent out to pick up groceries. Dutifully, the first two men follow the test plane, managing to fly directly above it. Thousands of feet in the air one of the men descends a rope ladder, gets onto the plane, kicks-in a window, crawls into the plane and cuts a key hose, sending the plane into a dive. He’s discovered by the Copperhead (the serial’s hero), beaten in a fight and tossed out of the plane to his doom. The Copperhead manages to gain control of the plane and makes an emergency landing in a field. Guess who’s there waiting for him: Dr. Satan’s two other men. Now that’s competence. (If you think following a plane by car is easy, try it sometime.) Take, for example, the henchmen of Dr. Satan, in “Mysterious Dr. Satan” (‘40 Republic). He’s after a new remote-controlled airplane being tested by the government. In Ch. 2 he tells two henchmen to get a plane of their own, follow the test plane, board it in mid air, and steal the remote control device. In case that doesn’t work, he orders two other goons to follow the plane by car, be wherever it lands, then steal the unit. The four men accept these assignments as if they were being sent out to pick up groceries. Dutifully, the first two men follow the test plane, managing to fly directly above it. Thousands of feet in the air one of the men descends a rope ladder, gets onto the plane, kicks-in a window, crawls into the plane and cuts a key hose, sending the plane into a dive. He’s discovered by the Copperhead (the serial’s hero), beaten in a fight and tossed out of the plane to his doom. The Copperhead manages to gain control of the plane and makes an emergency landing in a field. Guess who’s there waiting for him: Dr. Satan’s two other men. Now that’s competence. (If you think following a plane by car is easy, try it sometime.)

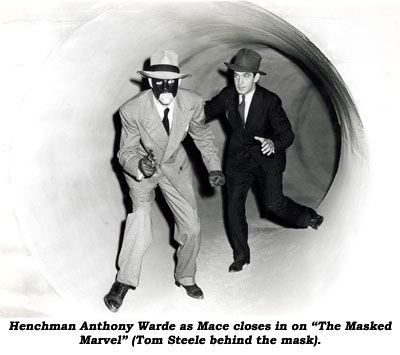

Then there’s “Killer” Mace (Anthony Warde), the right-hand man of master spy Sakima (Johnny Arthur) in “The Masked Marvel” (‘43 Republic), who, during an escape in the course of his duties, stands on the running board of a speeding truck and fires shots at the pursuing hero. Later, he’ll be obliged to move a highly explosive compound (nitroline) from one place to a small boat. Interrupted by the law, he executes a dive into the water and disappears under a dock. He also regularly engages in fist fights and shootouts with the hero and displays a remarkable talent for leaving the scene to narrowly avoid capture or just before an explosion. As part of an effort to steal industrial diamonds being shipped in a bullet-proof car, he kidnaps Lois (Ella Neal), the heroine, and singlehandedly, despite the Masked Marvel’s interference, succeeds in getting away with the diamonds. At one point he’s driving a truck when the Marvel pushes a pistol through the small opening between the truck’s van and cab, aims it at Mace’s head and tells him to keep going. Mace grabs the Marvel’s hand, disarms him, and still steering, steps on the gas to pick up speed, then leaps from the truck which careens wildly, flies off the mountain road and explodes. Mace gets away unhurt. Then there’s “Killer” Mace (Anthony Warde), the right-hand man of master spy Sakima (Johnny Arthur) in “The Masked Marvel” (‘43 Republic), who, during an escape in the course of his duties, stands on the running board of a speeding truck and fires shots at the pursuing hero. Later, he’ll be obliged to move a highly explosive compound (nitroline) from one place to a small boat. Interrupted by the law, he executes a dive into the water and disappears under a dock. He also regularly engages in fist fights and shootouts with the hero and displays a remarkable talent for leaving the scene to narrowly avoid capture or just before an explosion. As part of an effort to steal industrial diamonds being shipped in a bullet-proof car, he kidnaps Lois (Ella Neal), the heroine, and singlehandedly, despite the Masked Marvel’s interference, succeeds in getting away with the diamonds. At one point he’s driving a truck when the Marvel pushes a pistol through the small opening between the truck’s van and cab, aims it at Mace’s head and tells him to keep going. Mace grabs the Marvel’s hand, disarms him, and still steering, steps on the gas to pick up speed, then leaps from the truck which careens wildly, flies off the mountain road and explodes. Mace gets away unhurt.

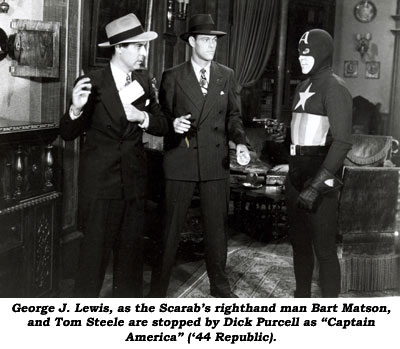

Another classic henchman is Bart Matson (George J. Lewis), the Scarab’s main man in “Captain America” (‘44 Republic). In addition to his many talents he’s tough enough to knock Captain America cold in a man-to-man fight and skilled enough to operate a just-developed futuristic weapon (the Firebolt). Like all main henchmen, Matson is uncannily proficient at repeatedly escaping from tight spots just before disaster strikes, can pilot a plane, and is stealthy enough to plant a listening device in the DA’s (Dick Purcell) apartment. Matson even dies and comes back to life, thanks to a life-restoring invention stolen by the Scarab. He’s also sharper than his boss, figuring out DA Gardner is Captain America long before the Scarab comes to the same conclusion. Unfortunately, his fate is undistinguished: he walks into a trap, is handcuffed and led ignominiously away. Another classic henchman is Bart Matson (George J. Lewis), the Scarab’s main man in “Captain America” (‘44 Republic). In addition to his many talents he’s tough enough to knock Captain America cold in a man-to-man fight and skilled enough to operate a just-developed futuristic weapon (the Firebolt). Like all main henchmen, Matson is uncannily proficient at repeatedly escaping from tight spots just before disaster strikes, can pilot a plane, and is stealthy enough to plant a listening device in the DA’s (Dick Purcell) apartment. Matson even dies and comes back to life, thanks to a life-restoring invention stolen by the Scarab. He’s also sharper than his boss, figuring out DA Gardner is Captain America long before the Scarab comes to the same conclusion. Unfortunately, his fate is undistinguished: he walks into a trap, is handcuffed and led ignominiously away.

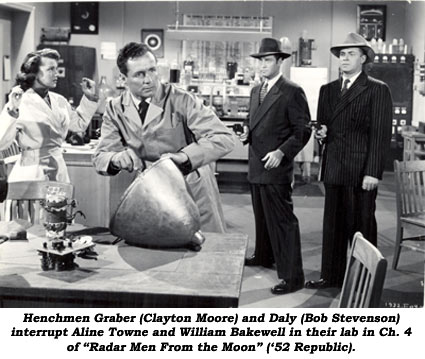

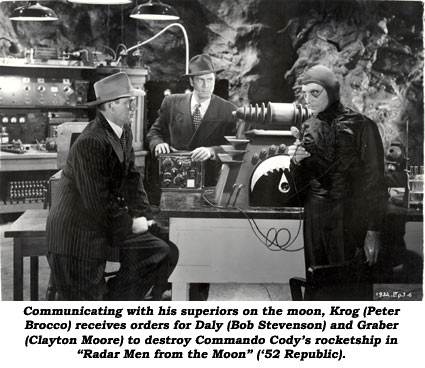

My favorite henchmen are the team of Graber and Daly (Clayton Moore and Bob Stevenson) (top pg. 7) in “Radar Men From the Moon” (‘52 Republic), primarily because they can rarely get anything right. Like all henchmen they’re loyal, fearless and obedient. All they lack is competence and brains. One of their first assignments is to blast a train with a ray gun they’ve set up in the back of a truck. Before they can strike they’re spotted by the hero, Commando Cody (George Wallace). After a brief gun battle they abandon the truck and flee on foot, leaving the weapon to Cody. Their boss, Moon-man Krog (Peter Brocco) orders them to go to Cody’s laboratory to retrieve the ray gun’s “atomic chamber”, one of the few missions they actually complete. When Krog learns Cody is heading back to earth from the moon in a rocketship, Graber and Daly are sent to destroy it “before anyone can get out of it.” As soon as Cody steps out of the ship the two would-be assassins open fire, and miss. When Cody returns fire, Daly gets nicked in the hand, Graber runs out of ammunition and they flee. In desperation, and critically short of Earth money, Krog orders Graber to resume his former career as a bank robber, which Graber does in earnest but with his usual skill. The robbery is botched, three of his underlings are killed and he has to leap from a speeding car to escape capture. Graber and Daly’s next assignment is to capture Cody so he can be held for ransom. “Cody should be worth at least a hundred thousand dollars,” Krog says. They don’t get Cody, but Graber captures his secretary, Joan (Aline Towne), gets her into a plane and pilots it with Cody (who, thanks to a remarkable suit he’s invented, can fly) in hot pursuit. There’s a pistol battle between Graber in the plane and Cody in the sky. When he runs out of ammunition (again) Graber bails out—another failed mission, leaving Cody to rescue Joan. Krog gives Graber and Daly (who might have fared better as a vaudeville team) one last chance to redeem themselves: a simple job, to steal a hotel’s payroll. But even this is too much for the dynamic duo who are wounded and caught. Eventually, Graber and Daly battle Cody and his buddy Ted (William Bakewell) in a cafe and, as usual, are forced to flee. During the ensuing high-speed auto chase, the duo’s car speeds off a mountain road and explodes spectacularly in a fitting end to one of serialdom’s more memorable henchmen teams. My favorite henchmen are the team of Graber and Daly (Clayton Moore and Bob Stevenson) (top pg. 7) in “Radar Men From the Moon” (‘52 Republic), primarily because they can rarely get anything right. Like all henchmen they’re loyal, fearless and obedient. All they lack is competence and brains. One of their first assignments is to blast a train with a ray gun they’ve set up in the back of a truck. Before they can strike they’re spotted by the hero, Commando Cody (George Wallace). After a brief gun battle they abandon the truck and flee on foot, leaving the weapon to Cody. Their boss, Moon-man Krog (Peter Brocco) orders them to go to Cody’s laboratory to retrieve the ray gun’s “atomic chamber”, one of the few missions they actually complete. When Krog learns Cody is heading back to earth from the moon in a rocketship, Graber and Daly are sent to destroy it “before anyone can get out of it.” As soon as Cody steps out of the ship the two would-be assassins open fire, and miss. When Cody returns fire, Daly gets nicked in the hand, Graber runs out of ammunition and they flee. In desperation, and critically short of Earth money, Krog orders Graber to resume his former career as a bank robber, which Graber does in earnest but with his usual skill. The robbery is botched, three of his underlings are killed and he has to leap from a speeding car to escape capture. Graber and Daly’s next assignment is to capture Cody so he can be held for ransom. “Cody should be worth at least a hundred thousand dollars,” Krog says. They don’t get Cody, but Graber captures his secretary, Joan (Aline Towne), gets her into a plane and pilots it with Cody (who, thanks to a remarkable suit he’s invented, can fly) in hot pursuit. There’s a pistol battle between Graber in the plane and Cody in the sky. When he runs out of ammunition (again) Graber bails out—another failed mission, leaving Cody to rescue Joan. Krog gives Graber and Daly (who might have fared better as a vaudeville team) one last chance to redeem themselves: a simple job, to steal a hotel’s payroll. But even this is too much for the dynamic duo who are wounded and caught. Eventually, Graber and Daly battle Cody and his buddy Ted (William Bakewell) in a cafe and, as usual, are forced to flee. During the ensuing high-speed auto chase, the duo’s car speeds off a mountain road and explodes spectacularly in a fitting end to one of serialdom’s more memorable henchmen teams.

You have to wonder what henchmen expected to get out of all this. The thought often occurred to me when I was a kid watching these serials. There’s rarely mention of the specific salary or reward they can expect. At one point in “Radar Men”, Krog admonishes a balky Graber by telling him he’s being “well paid.” But what kind of salary would encourage anyone to lower himself onto the roof of a hostile airplane? Yes, real-life pilots and stuntpeople often performed this kind of act at fairs or for movies, but the planes were not occupied by passengers who would shoot them on sight. This is the kind of question that demands a “suspension of disbelief,” an absolute requirement for anyone who loves serials. Regardless of their motivations, one thing’s for sure about henchmen: the master villain would have been helpless without them. You have to wonder what henchmen expected to get out of all this. The thought often occurred to me when I was a kid watching these serials. There’s rarely mention of the specific salary or reward they can expect. At one point in “Radar Men”, Krog admonishes a balky Graber by telling him he’s being “well paid.” But what kind of salary would encourage anyone to lower himself onto the roof of a hostile airplane? Yes, real-life pilots and stuntpeople often performed this kind of act at fairs or for movies, but the planes were not occupied by passengers who would shoot them on sight. This is the kind of question that demands a “suspension of disbelief,” an absolute requirement for anyone who loves serials. Regardless of their motivations, one thing’s for sure about henchmen: the master villain would have been helpless without them.

Richard Cramer

The ugly, over-bearing, savage, gravel-voiced snarl of Richard (Dick) Cramer scared the beejesus out of front-row kids in the ‘30s and ‘40s in a dozen serials. He’s also well remembered by “tents” of Laurel and Hardy devotees for his menace to the comedy duo in “Scram!” (‘32), “Pack Up Your Troubles” (‘32), “Flying Deuces” (‘39) and especially “Saps at Sea” (‘40) as the escaped convict. Then there were his westerns.

The bulldog Irish mug of Richard Cramer first saw the light of day on July 3, 1889, in Bryan, Ohio. A graduate of Ohio State University, Cramer didn’t come to films in the late silent period (1928) until he was 39. But from then until 1952 he worked nonstop in well over 200 films.

Cramer’s exaggerated malevolence was ripe for serials, and he appeared in 12 of them, beginning with a silent, “The Tiger’s Shadow” (Pathe) in ‘28. He was prominent as a thug in “The Vanishing Shadow” (‘34 Universal) and “Black Coin” (‘36 Stage and Screen); trying to steal Rex, King of the Wild Horses, in “Law of the Wild” (‘34 Mascot); Joe Portos, Mexican bandit in “Red Rider” (‘36 Universal) and as the Apache killer in “Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok” (‘38 Columbia). He also had roles in “Adventures of Frank Merriwell” (‘36), “Radio Patrol” (‘37), “White Eagle” (‘41), “Tailspin Tommy” (‘34), “Iron Claw” (‘41), and “Who’s Guilty” (‘45). There’s also a possibility Cramer was the voice of the Black Tiger in Columbia’s “The Shadow” (‘40). Hal Polk and I agree it sounds like him. Can anyone confirm? Cramer’s exaggerated malevolence was ripe for serials, and he appeared in 12 of them, beginning with a silent, “The Tiger’s Shadow” (Pathe) in ‘28. He was prominent as a thug in “The Vanishing Shadow” (‘34 Universal) and “Black Coin” (‘36 Stage and Screen); trying to steal Rex, King of the Wild Horses, in “Law of the Wild” (‘34 Mascot); Joe Portos, Mexican bandit in “Red Rider” (‘36 Universal) and as the Apache killer in “Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok” (‘38 Columbia). He also had roles in “Adventures of Frank Merriwell” (‘36), “Radio Patrol” (‘37), “White Eagle” (‘41), “Tailspin Tommy” (‘34), “Iron Claw” (‘41), and “Who’s Guilty” (‘45). There’s also a possibility Cramer was the voice of the Black Tiger in Columbia’s “The Shadow” (‘40). Hal Polk and I agree it sounds like him. Can anyone confirm?

Increasingly, from 1940 on, Cramer began to play grouchy bartenders in westerns. Matter of fact, he’s prominent as the bartender in his next to last film, “Santa Fe” (‘52) with Randolph Scott. His bartending actually dates back to serving booze in the independently made “Face On the Barroom Floor” in ‘32. Totaling up his barkeep pics finds him tending bar in over 30 films…not to count his saloon owner roles in westerns. Ironically, Cramer died from cirrhosis of the liver August 9, 1960, in LA.

At the cliffhanger of Ch. 6 of “Miracle Rider”, Tom Mix is felled from Tony as outlaws ride over him. Alas, in Ch. 7 the badmen simply ride slowly up to where Tom’s body lies, not over him. |

top of page |