|

|

Chapter One Hundred Sixteen

Introduction

by Boyd Magers

Tunesmith/composer Leo (Lee) Zahler was the eldest of three sons and a daughter born to Austro-Hungarian Jews who had immigrated to America a decade or so before the turn of the 20th Century. Lee Zahler was born August 14, 1893 in New York City. His father, although a pattern designer in the garment business, encouraged Lee in his musical studies. His first professional work was for a New York music publisher and as a theatrical piano player. By the early ‘20s Zahler was employed by silent film pioneer Thomas Ince, both playing in accompaniment to silent flickers and writing music for them. Ince, the legendary ‘Father of the Western’ provided Zahler with an arena for developing his craft. By this time Zahler had to his credit over 200 original compositions which were used in silent film theatres. He became music director for Larry Darmour’s film studio before moving on to contribute to Abe Meyer’s Synchronizing Service which provided music for movies in the new era of sound. In 1938 Zahler went freelance, offering strong competition to Meyer with his own music library and taking assignments with various studios and producers. Over the course of his phenomenal career, Zahler worked on over 300 features and serials—with which Edward Rose’s article is concerned...

The Music of Lee Zahler The Music of Lee Zahler

by Edward Rose,

writer, playwright, and poet whose works have been published in both national and international publications

Along with other film elements, the musical score contributes to the essence of a successful and entertaining motion picture. Specifically, it establishes the appropriate mood, identifies a particular character or setting, punctuates the action or emotion and seamlessly connects the scenes. A good score exerts powerful influence upon a motion picture. In some instances, it can even make the picture better. Along with other film elements, the musical score contributes to the essence of a successful and entertaining motion picture. Specifically, it establishes the appropriate mood, identifies a particular character or setting, punctuates the action or emotion and seamlessly connects the scenes. A good score exerts powerful influence upon a motion picture. In some instances, it can even make the picture better.

Writing music for serials required a special discipline because of time and budget constraints. Working within those rigid constraints, Zahler still managed to write music scores that were usually interesting, often provocative, and consistently good. His music possesses several distinctive characteristics: 1) Shifting moods and unusual rhythms. 2) Complex orchestration incorporating the harp within the harmonic and thematic structure. 3) Use of themes from classical music, with original variations and interpolations. 4) Use of leitmotivs, a musical concept developed by Richard Wagner, whereby a recurring theme or series of notes identifies a character, incident, or emotion. For some reason, Zahler’s artistry has never been duly acknowledged, nor fully appreciated.

In the early years serial music lacked the conception, complexity, scope and variety of symphonic music. Stock music from other movies was often merged into the music score, and this music usually had little relevance to the plot or action of the scene. For example, Universal rarely used original music scores in serials. The “Flash Gordon”

serials included music from such diverse sources as “Bride of Frankenstein”. The main theme of “Riders of Death Valley” (‘41) was Felix Mendelssohn’s “Fingal’s Cave” and stock music from numerous Johnny Mack Brown Westerns. In contrast, Republic commissioned and encouraged its composers—Alberto Colombo, Raoul Kraushaar, William Lava, Cy Feuer and Mort Glickman, to name a few—to create original compositions for its serials. Columbia also opted for original music scores, many of which were written by Zahler. serials included music from such diverse sources as “Bride of Frankenstein”. The main theme of “Riders of Death Valley” (‘41) was Felix Mendelssohn’s “Fingal’s Cave” and stock music from numerous Johnny Mack Brown Westerns. In contrast, Republic commissioned and encouraged its composers—Alberto Colombo, Raoul Kraushaar, William Lava, Cy Feuer and Mort Glickman, to name a few—to create original compositions for its serials. Columbia also opted for original music scores, many of which were written by Zahler.

During these early years, Zahler honed and polished his skills by writing several music scores for Mascot Pictures. These included “Phantom of the West” (‘31), “The Three

Musketeers” (‘33), “Hurricane Express” (‘32), “Mystery Squadron” (‘33), “Mystery Mountain” (‘34),“Fighting With Kit Carson” (‘33), “Law of the Wild” (‘34), “Fighting Marines” (‘35), Adventures of Rex and Rinty” (‘35) and “Miracle Rider” (‘35), among others. In addition, Zahler wrote the scores for several independent serial producers including Krellberg Pictures’ “Lost City” (‘35) and Stage and Screen Productions’ “Clutching Hand” (‘36). In 1935 Mascot and several other small, independent studios merged with Herbert Yates’ Consolidated Film Laboratories to form Republic Pictures. One of Republic’s first serials was “Vigilantes Are Coming” (‘36). The music score was attributed to Harry Gray, even though Zahler wrote portions of it and Musketeers” (‘33), “Hurricane Express” (‘32), “Mystery Squadron” (‘33), “Mystery Mountain” (‘34),“Fighting With Kit Carson” (‘33), “Law of the Wild” (‘34), “Fighting Marines” (‘35), Adventures of Rex and Rinty” (‘35) and “Miracle Rider” (‘35), among others. In addition, Zahler wrote the scores for several independent serial producers including Krellberg Pictures’ “Lost City” (‘35) and Stage and Screen Productions’ “Clutching Hand” (‘36). In 1935 Mascot and several other small, independent studios merged with Herbert Yates’ Consolidated Film Laboratories to form Republic Pictures. One of Republic’s first serials was “Vigilantes Are Coming” (‘36). The music score was attributed to Harry Gray, even though Zahler wrote portions of it and

compiled the stock music augmented by Beethoven’s “Egmont Overture”. This was one of Zahler’s earliest uses of classical music in a serial score but contained no original variations or contributions on his part. As the serial evolved, a certain format became common for his music scores. Four separate themes were reused—main titles, action, incidental music and end titles. Western serials might also have a chase music theme. compiled the stock music augmented by Beethoven’s “Egmont Overture”. This was one of Zahler’s earliest uses of classical music in a serial score but contained no original variations or contributions on his part. As the serial evolved, a certain format became common for his music scores. Four separate themes were reused—main titles, action, incidental music and end titles. Western serials might also have a chase music theme.

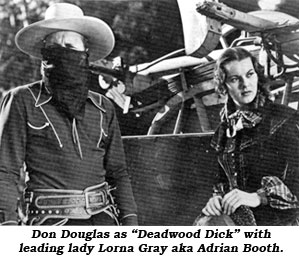

Zahler’s distinctive, individual style evolved and developed from ‘39-‘44, the most creative and productive phase of his career. Zahler was under contract to Columbia where Morris Stoloff was music director and George Duning was the resident composer, so Zahler was relegated to writing music for the studio’s B-movies. His output was prolific and impressive, writing the music scores for several Crime Doctor and Ellery Queen mysteries along with many serials including “Deadwood Dick” (‘40), “Green Archer” (‘40), “The Shadow” (‘40), “Terry and the Pirates” (‘40), “The Spider Returns” (‘41), “White Eagle” (‘41), “The Iron Claw” (‘41), “Holt of the Secret Service” (‘41), “Captain Midnight” (‘42), “Perils of the Royal Mounted” (‘42), “Valley of Vanishing Men” (‘42), “Secret Code” (‘42), “Batman” (‘43) and “The Phantom” (‘43). The scores of some of these films represent Zahler’s best work. Zahler might have also written major portions of the music scores of Republic’s “Drums of Fu Manchu” (‘40) and “Mysterious Dr. Satan” (‘40), along with lesser portions of “Adventures of Captain Marvel” (‘40). However, Cy Feuer, music director at the time, is given credit for writing these music scores.

Although the serial “Deadwood Dick” is not highly regarded, it’s the logical choice to begin any analysis of Zahler’s music because it contains several characteristics of his mature style and provides valuable insights and clues to the music scores of other serials he wrote. An obbligato by woodwinds ushers in the main title theme and buttresses the principal theme, which is carried by trumpets, then assumed by trombones. The theme concludes on an air of uncertainty in a series of isolated notes by trumpet, trombone and French horns. Two action themes are featured throughout the score. The first is a spirited, lilting melody played by full orchestra, with brass prominent and interspersed with string glissandos. It’s heard near the end of Chapter 1, when Deadwood Dick is desperately searching for Jack McCall. Zahler was very fond of this theme; it re-appears in “Perils of the Royal Mounted”. The second action theme, a charming variation on a passage from Wagner’s “Tannhauser Overture”, makes its initial appearance in the beginning of Chapter 2. An ominous leitmotiv is identified with the villain of the serial, the Skull. Incidental music is the same four-note figure by woodwinds that comprises the main title theme of “Mysterious Dr. Satan”. This music re-appears in other works of Zahler, such Although the serial “Deadwood Dick” is not highly regarded, it’s the logical choice to begin any analysis of Zahler’s music because it contains several characteristics of his mature style and provides valuable insights and clues to the music scores of other serials he wrote. An obbligato by woodwinds ushers in the main title theme and buttresses the principal theme, which is carried by trumpets, then assumed by trombones. The theme concludes on an air of uncertainty in a series of isolated notes by trumpet, trombone and French horns. Two action themes are featured throughout the score. The first is a spirited, lilting melody played by full orchestra, with brass prominent and interspersed with string glissandos. It’s heard near the end of Chapter 1, when Deadwood Dick is desperately searching for Jack McCall. Zahler was very fond of this theme; it re-appears in “Perils of the Royal Mounted”. The second action theme, a charming variation on a passage from Wagner’s “Tannhauser Overture”, makes its initial appearance in the beginning of Chapter 2. An ominous leitmotiv is identified with the villain of the serial, the Skull. Incidental music is the same four-note figure by woodwinds that comprises the main title theme of “Mysterious Dr. Satan”. This music re-appears in other works of Zahler, such

as “Perils of the Royal Mounted”, “The Phantom” and several B-Western films of his later period. Since the laws governing plagiarism are stringent and severe, and since this was an entirely different studio, we might safely conclude Zahler is the composer of this music, and that in all likelihood he composed the music while working on the music score of “Mysterious Dr. Satan”. No composer, for reasons of ego and vanity, would intentionally use another’s work without proper acknowledgment. Another strong indication that he wrote major portions of the music score of “Mysterious Dr. Satan” is the prominence of the harp in this score. Both the main title and end title themes of this film are embellished with arpeggios fortezza by the harp. Although the harp is a staple of the contemporary 75 piece symphony orchestra, its prominence in the score of a serial is unusual and unprecedented. Not only is it difficult writing music for this instrument, it’s equally difficult to find skillful players. The strings require constant mending and the instrument is inconvenient to move. There are also practical reasons for not using a harp. A typical orchestra for a small studio might, under optimal conditions, comprise 20-25 musicians—13 strings (eight violins, four violas, one string bass), four woodwinds (oboe, clarinet, bassoon and flute) four brass (trumpet, trombone and two French horns) and timpani. Most composers would probably prefer adding another violin or woodwind, yet Zahler regularly used the harp in his music scores. In that respect he was unique. In conception, complexity, scope and variety, the music score of “Mysterious Dr. Satan” might be the best ever written for a serial. Its two action themes would regularly re-appear in subsequent Republic serials, including “Dick Tracy Vs. Crime Inc.” (‘41), “Manhunt of Mystery Island” (‘45), “Purple Monster Strikes” (‘45) and others. Even as late as Chapter 15, fresh musical themes were being introduced. as “Perils of the Royal Mounted”, “The Phantom” and several B-Western films of his later period. Since the laws governing plagiarism are stringent and severe, and since this was an entirely different studio, we might safely conclude Zahler is the composer of this music, and that in all likelihood he composed the music while working on the music score of “Mysterious Dr. Satan”. No composer, for reasons of ego and vanity, would intentionally use another’s work without proper acknowledgment. Another strong indication that he wrote major portions of the music score of “Mysterious Dr. Satan” is the prominence of the harp in this score. Both the main title and end title themes of this film are embellished with arpeggios fortezza by the harp. Although the harp is a staple of the contemporary 75 piece symphony orchestra, its prominence in the score of a serial is unusual and unprecedented. Not only is it difficult writing music for this instrument, it’s equally difficult to find skillful players. The strings require constant mending and the instrument is inconvenient to move. There are also practical reasons for not using a harp. A typical orchestra for a small studio might, under optimal conditions, comprise 20-25 musicians—13 strings (eight violins, four violas, one string bass), four woodwinds (oboe, clarinet, bassoon and flute) four brass (trumpet, trombone and two French horns) and timpani. Most composers would probably prefer adding another violin or woodwind, yet Zahler regularly used the harp in his music scores. In that respect he was unique. In conception, complexity, scope and variety, the music score of “Mysterious Dr. Satan” might be the best ever written for a serial. Its two action themes would regularly re-appear in subsequent Republic serials, including “Dick Tracy Vs. Crime Inc.” (‘41), “Manhunt of Mystery Island” (‘45), “Purple Monster Strikes” (‘45) and others. Even as late as Chapter 15, fresh musical themes were being introduced.

The prominence of the harp in one of the main action themes of Republic’s “Drums of Fu Manchu” leads us to believe Zahler might have written portions of that serial as well. Agitated strings, swirling up the chromatic scale (similar to the opening bars of “Secret Code”), with rippling arpeggios Fortezza interjected by the harp, are aspects of Zahler’s inimitable style, and they are definitely present in this action theme. Zahler’s contributions to the music score of Republic’s “Adventures of Captain Marvel”—brief passages by the harp in the main and end titles, with certain themes that also appear in the incidental music of “The Spider Returns”—seem minimal, so we may reasonably assume Zahler is the composer of those portions of the music score.

Serial aficionados quickly dismiss the “Batman” serial as an unmitigated disaster.  However, the score is something entirely different. The theme for the main title is a variation from Wagner’s “Rienzi Overture”. Dark, brooding, moody and mysterious, the music reflects the sure, deft touch of a master composer gifted with a dazzling array of skills. All of the characteristics of Zahler’s unique personal style are on display— varying moods, unusual rhythms, complex orchestration featuring the harp, use of a classical theme with original variations and use of a leitmotiv. This might very well be Zahler’s masterpiece. After an ominous opening passage featuring oboe and harp, the main title—a tour de force for brass—is introduced. The theme alternates among trumpet, horns and trombone before finding resolution in an unresolved seventh chord. Lush chords and arpeggio agevole by the harp precede each mutation of the theme as it traverses the brass instruments. It was Zahler’s most lavish and spectacular employment of the harp. Another spirited romp, in many ways similar to the action theme of “The Green Archer”, characterizes the principal action there. Whenever Batman unexpectedly confronts the villains, a lefmotiv accompanies his appearance. A secondary action theme and new incidental music are introduced in Chapter 7. However, the score is something entirely different. The theme for the main title is a variation from Wagner’s “Rienzi Overture”. Dark, brooding, moody and mysterious, the music reflects the sure, deft touch of a master composer gifted with a dazzling array of skills. All of the characteristics of Zahler’s unique personal style are on display— varying moods, unusual rhythms, complex orchestration featuring the harp, use of a classical theme with original variations and use of a leitmotiv. This might very well be Zahler’s masterpiece. After an ominous opening passage featuring oboe and harp, the main title—a tour de force for brass—is introduced. The theme alternates among trumpet, horns and trombone before finding resolution in an unresolved seventh chord. Lush chords and arpeggio agevole by the harp precede each mutation of the theme as it traverses the brass instruments. It was Zahler’s most lavish and spectacular employment of the harp. Another spirited romp, in many ways similar to the action theme of “The Green Archer”, characterizes the principal action there. Whenever Batman unexpectedly confronts the villains, a lefmotiv accompanies his appearance. A secondary action theme and new incidental music are introduced in Chapter 7.

“The Secret Code” was one of the better serials from Columbia. Fast-paced, skillful  editing and crisp direction by Spencer Bennet helped create an ambiance and mystique similar to that of a well-made Republic serial. In fact, “The Secret Code” has often been favorably compared to Republic’s “Spy Smasher” (‘42), a serial cited by many critics as the best ever made. Both had music scores based upon the first movement of Beethoven’s “Fifth Symphony”. Mort Glickman composed the music score for “Spy Smasher”. His music was functional, effective and workmanlike, with little variation on the basic theme. In contrast, Zahler’s music score was much more arresting and dramatic, with considerable variation on the basic theme and the imposition of a highly personal, distinctive style. The opening measures of the main title theme consist of the familiar four-note motif delivered by solo trumpet swirling upward, followed by agitated strings, similar to the opening measures of the action theme of “Drums of Fu Manchu”. A brief pause ensues, followed by notes imitating a cipher or decoding machine. This sequence is recapitulated and segues into full orchestral development, leading to resolution with a statement by full orchestra and ending with solo trumpet repeating the four-note motif. The theme for the end titles repeats the same cipher notes followed by a triumphant restatement of the familiar four-note motif by full orchestra with emphatic timpani to conclude the music. Action theme music is yet another variation of the familiar four-note motif, with extensive and varied orchestral development. Incidental music is more complex and noticeably superior to the bland, innocuous pabulum typically found in the incidental music of some serials. This was Zahler’s second most impressive music score. editing and crisp direction by Spencer Bennet helped create an ambiance and mystique similar to that of a well-made Republic serial. In fact, “The Secret Code” has often been favorably compared to Republic’s “Spy Smasher” (‘42), a serial cited by many critics as the best ever made. Both had music scores based upon the first movement of Beethoven’s “Fifth Symphony”. Mort Glickman composed the music score for “Spy Smasher”. His music was functional, effective and workmanlike, with little variation on the basic theme. In contrast, Zahler’s music score was much more arresting and dramatic, with considerable variation on the basic theme and the imposition of a highly personal, distinctive style. The opening measures of the main title theme consist of the familiar four-note motif delivered by solo trumpet swirling upward, followed by agitated strings, similar to the opening measures of the action theme of “Drums of Fu Manchu”. A brief pause ensues, followed by notes imitating a cipher or decoding machine. This sequence is recapitulated and segues into full orchestral development, leading to resolution with a statement by full orchestra and ending with solo trumpet repeating the four-note motif. The theme for the end titles repeats the same cipher notes followed by a triumphant restatement of the familiar four-note motif by full orchestra with emphatic timpani to conclude the music. Action theme music is yet another variation of the familiar four-note motif, with extensive and varied orchestral development. Incidental music is more complex and noticeably superior to the bland, innocuous pabulum typically found in the incidental music of some serials. This was Zahler’s second most impressive music score.

As an unerring arrow strikes the center of an ancient door at Garr Castle, a clash of  cymbals ushers in the main title theme of “The Green Archer”, a marvelously complex melody propelled by a trombone that slowly descends the chromatic scale, punctuated step-by-step with forceful timpani. A convoluted, tortuous passage, first stated by trumpet and then repeated by trombone, follows. The theme— mysterious and portentous, with a stifling aura of foreboding—undergoes many dramatic permutations before finding resolution on a somewhat subdued note. Garr Castle was the main setting of the serial. It was literally a ‘den of iniquity’, the hideout for a dastardly gang of jewel thieves. With its many hidden rooms, dungeons, trap doors, collapsing floors, converging walls and secret passages, the castle posed a constant source of peril to the unwary. The principal action theme, introduced near the end of Chapter 1, is yet another of those stirring galvanizing tunes that seems to flow with such effortless ease from the creative fount of Zahler. A leitmotiv presages each appearance of the Green Archer. Zahler’s music score for “The Green Archer” is strikingly original. It perfectly captured the aura of menace and mystery that permeated Garr Castle. cymbals ushers in the main title theme of “The Green Archer”, a marvelously complex melody propelled by a trombone that slowly descends the chromatic scale, punctuated step-by-step with forceful timpani. A convoluted, tortuous passage, first stated by trumpet and then repeated by trombone, follows. The theme— mysterious and portentous, with a stifling aura of foreboding—undergoes many dramatic permutations before finding resolution on a somewhat subdued note. Garr Castle was the main setting of the serial. It was literally a ‘den of iniquity’, the hideout for a dastardly gang of jewel thieves. With its many hidden rooms, dungeons, trap doors, collapsing floors, converging walls and secret passages, the castle posed a constant source of peril to the unwary. The principal action theme, introduced near the end of Chapter 1, is yet another of those stirring galvanizing tunes that seems to flow with such effortless ease from the creative fount of Zahler. A leitmotiv presages each appearance of the Green Archer. Zahler’s music score for “The Green Archer” is strikingly original. It perfectly captured the aura of menace and mystery that permeated Garr Castle.

“A fabulous fortune is at stake. The Iron Claw is hot on the trail. He lurks in the dark; he strikes in the back.” With the narrator’s chilling words as a spur, Zahler wrote the music score for “The Iron Claw”, another exemplar of program music. In this serial, the emphasis appears to be upon the evil residing in a person—a paranoid killer desperately seeking fortune in gold. Following a few uncertain, portentous bars by trumpet, accentuated by emphatic timpani and a few equally portentous bars by trombone (also accentuated by ominous timpani), the main title theme makes the transition to full orchestra with violas dominating. After further orchestral development, the theme is assumed by violins and quietly concludes. Emphasis upon timpani and the deliberately ominous tone are not merely coincidental nor theatrical—they are planned, intrinsic elements of the composer’s grand vision. It requires no wild stretch of the imagination to believe the composer intended the timpani to simulate the sound of footsteps. Although not a great music score, “The Iron Claw” does show some of the more important traits of the composer’s distinctive style—dramatic tempo changes, unusual rhythms, complex orchestration and leitmotiv. “A fabulous fortune is at stake. The Iron Claw is hot on the trail. He lurks in the dark; he strikes in the back.” With the narrator’s chilling words as a spur, Zahler wrote the music score for “The Iron Claw”, another exemplar of program music. In this serial, the emphasis appears to be upon the evil residing in a person—a paranoid killer desperately seeking fortune in gold. Following a few uncertain, portentous bars by trumpet, accentuated by emphatic timpani and a few equally portentous bars by trombone (also accentuated by ominous timpani), the main title theme makes the transition to full orchestra with violas dominating. After further orchestral development, the theme is assumed by violins and quietly concludes. Emphasis upon timpani and the deliberately ominous tone are not merely coincidental nor theatrical—they are planned, intrinsic elements of the composer’s grand vision. It requires no wild stretch of the imagination to believe the composer intended the timpani to simulate the sound of footsteps. Although not a great music score, “The Iron Claw” does show some of the more important traits of the composer’s distinctive style—dramatic tempo changes, unusual rhythms, complex orchestration and leitmotiv.

“Terry and the Pirates” is one of Zahler’s more delightful music scores. The main theme is richly textured with complex orchestration and several changes in rhythm and tempos. To enhance the stylization, oriental melodies were incorporated into the music score and unusual instruments were added, such as gongs, cymbals, gourds and celesta, infusing the orchestration with a decidedly exotic flavoring. Because the serial itself is obtuse, stultifying and dull, the music score might be equated to an exquisite gem. “Terry and the Pirates” is one of Zahler’s more delightful music scores. The main theme is richly textured with complex orchestration and several changes in rhythm and tempos. To enhance the stylization, oriental melodies were incorporated into the music score and unusual instruments were added, such as gongs, cymbals, gourds and celesta, infusing the orchestration with a decidedly exotic flavoring. Because the serial itself is obtuse, stultifying and dull, the music score might be equated to an exquisite gem.

Apparently, Columbia allocated a generous budget for the production of “The  Phantom”, and Zahler was the principal beneficiary. His music score contains more music than is typically found in most Columbia serials. The main theme is derivative from “Terry and the Pirates”, but the orchestration is not as tight nor as complex. The oriental hues are more subdued, and most of the exotic instruments, except the gong, have been discarded. It begins with an oriental gong, an arpeggio agevole by harp and a tortuous violin passage. Full orchestral development with subtle oriental flavoring and rhythm ensues, featuring dominant trumpet followed by a brief oboe solo arabesque. Incidental music is plentiful and varied. One segment consists of the four-note melody by woodwinds from the main title theme of “Mysterious Dr. Satan”, which also appears in “Deadwood Dick” and “Perils of the Royal Mounted”. Another segment—an intricate, exotic arrangement for woodwinds, solo violin, harp and timpani—resonates with all the beauty, mystery and magic of the orient (see the end of Chapter 9). There is even a clever snippet from Wagner’s “Rienzi Overture”, which was the basis for the Batman score. Action themes are equally varied. One theme is derivative from the action theme of “The Green Archer”. Another segment has a melody reminiscent of Native American music, featuring emphatic tom-toms. All are spirited and effectively complement the action. Phantom”, and Zahler was the principal beneficiary. His music score contains more music than is typically found in most Columbia serials. The main theme is derivative from “Terry and the Pirates”, but the orchestration is not as tight nor as complex. The oriental hues are more subdued, and most of the exotic instruments, except the gong, have been discarded. It begins with an oriental gong, an arpeggio agevole by harp and a tortuous violin passage. Full orchestral development with subtle oriental flavoring and rhythm ensues, featuring dominant trumpet followed by a brief oboe solo arabesque. Incidental music is plentiful and varied. One segment consists of the four-note melody by woodwinds from the main title theme of “Mysterious Dr. Satan”, which also appears in “Deadwood Dick” and “Perils of the Royal Mounted”. Another segment—an intricate, exotic arrangement for woodwinds, solo violin, harp and timpani—resonates with all the beauty, mystery and magic of the orient (see the end of Chapter 9). There is even a clever snippet from Wagner’s “Rienzi Overture”, which was the basis for the Batman score. Action themes are equally varied. One theme is derivative from the action theme of “The Green Archer”. Another segment has a melody reminiscent of Native American music, featuring emphatic tom-toms. All are spirited and effectively complement the action.

Zahler’s last serial work was on “Jack Armstrong” (‘47). He spent the latter period of his career as music director of Producers Releasing Corp, primarily writing music for B-Westerns and low-budget film noirs. It’s believed he never wrote any other music scores for serials. He died on Feb. 21, 1947. Zahler’s last serial work was on “Jack Armstrong” (‘47). He spent the latter period of his career as music director of Producers Releasing Corp, primarily writing music for B-Westerns and low-budget film noirs. It’s believed he never wrote any other music scores for serials. He died on Feb. 21, 1947.

What conclusions can we make about his legacy? To say he was talented is obvious. He was well-trained, with a thorough background in classical music. He played several instruments well, including the harp, and he was a dedicated artist whose full potential may not have been realized because he was never afforded the opportunity of composing for a large 75 member orchestra for a studio such as Warner Bros., MGM or 20th Century Fox. It seems Zahler was not unduly influenced by the material he was occasionally given. The quality of his music remained uniformly high despite the quality of the serial. Most of all, he had something that all great artists possess—a distinctive style. That’s something that can’t be taught. Legendary film music composers of Hollywood’s Golden Age, such as Miklos Rozsa, Max Steiner, Erich Korngold, Dimitri Tiomkin, Hugo Friedhofer and Franz Waxman, had recognizable styles. Zahler’s musical skills might not be as lofty, but they do not suffer by comparison. In the genre he chose to work, he excelled! He was an undisputed master with a distinctive, recognizable style characterized by shifting moods and unusual rhythms. He used complex orchestration incorporating the harp, classical themes with original variations and interpolations and use of leitmotivs. The films on which he worked were more interesting and enjoyable thanks to his artistry. Any composer would be proud of such a legacy.

Tragedy struck Zahler in 1940 when his son Gordon (1926-1975) suffered a broken neck at 14 while performing high school gymnastics which left him a quadriplegic for life. The trauma and tribulation of dealing with this heartbreak, along with its financial repercussions, brought about the end of Lee’s marriage, and quite possibly his own premature passing in ‘47 at the age of only 53, a sad and regrettable end for a man who had serenaded us through three decades of musical change and innovation in film making. A final note: Gordon Zahler (right), despite his debilitating handicap, went on to follow the trail blazed by his father in providing music for films, often utilizing the elder Zahler’s music library along with other acquisitions such as TV’s “Craig Kennedy, Criminologist” (‘52), “26 Men” (‘57-‘59), Ed Wood’s “Plan Nine From Outer Space” and “Night of the Ghouls” (both ‘59) as well as music supervision on many TV shows. Tragedy struck Zahler in 1940 when his son Gordon (1926-1975) suffered a broken neck at 14 while performing high school gymnastics which left him a quadriplegic for life. The trauma and tribulation of dealing with this heartbreak, along with its financial repercussions, brought about the end of Lee’s marriage, and quite possibly his own premature passing in ‘47 at the age of only 53, a sad and regrettable end for a man who had serenaded us through three decades of musical change and innovation in film making. A final note: Gordon Zahler (right), despite his debilitating handicap, went on to follow the trail blazed by his father in providing music for films, often utilizing the elder Zahler’s music library along with other acquisitions such as TV’s “Craig Kennedy, Criminologist” (‘52), “26 Men” (‘57-‘59), Ed Wood’s “Plan Nine From Outer Space” and “Night of the Ghouls” (both ‘59) as well as music supervision on many TV shows.

Lee Zahler’s Serials

“Lone Defender” (‘30 Mascot)

“Phantom of the West (‘31 Mascot)

“King of the Wild” (‘31 Mascot)

“Vanishing Legion (‘31 Mascot)

“Galloping Ghost” (‘31 Mascot)

“Lightning Warrior” (‘31 Mascot) “Lightning Warrior” (‘31 Mascot)

“Shadow of the Eagle” (‘32 Mascot)

“Hurricane Express” (‘32 Mascot)

“Three Musketeers” (‘33 Mascot)

“Whispering Shadow” (‘33 Mascot)

“Fighting With Kit Carson” (‘33 Mascot)

“Gordon of Ghost City” (‘33 Universal)

“Mystery Squadron” (‘33 Mascot)

“Law of the Wild” (‘34 Mascot)

“Mystery Mountain” (‘34 Mascot)

“Fighting Marines” (‘35 Mascot)

“Adventures of Rex and Rinty” (‘35 Mascot)

“Miracle Rider” (‘35 Mascot)

“Lost City” (‘35 Krellberg)

“The Clutching Hand” (‘36 Stage & Screen)

“Black Coin” (‘36 Weiss-Mintz)

“Vigilantes Are Coming” (‘36 Republic)

“Shadow of Chinatown” (‘36 Victory)

“Blake of Scotland Yard” (‘37 Victory)

“Flying G-Men” (‘39 Columbia)

“Mandrake the Magician” (‘39 Columbia)

“Overland With Kit Carson” (‘39 Columbia)

“The Shadow” (‘39 Columbia)

“Terry and the Pirates” (‘40 Columbia)

“Deadwood Dick” (‘40 Columbia)

“Green Archer” (‘40 Columbia)

“White Eagle” (‘41 Columbia)

“Iron Claw” (‘41 Columbia)

“The Spider Returns” (‘41 Columbia)

“Holt of the Secret Service” (‘41 Columbia)

“Captain Midnight” (‘42 Columbia)

“Perils of the Royal Mounted (‘42 Columbia)

“Secret Code” (‘42 Columbia)

“Valley of Vanishing Men” (‘42 Columbia)

“Batman” (‘42 Columbia)

“The Phantom” (‘43 Columbia)

“Desert Hawk” (‘44 Columbia)

“Black Arrow” (‘44 Columbia)

“Monster and the Ape” (‘45 Columbia)

“Jungle Raiders” (‘45 Columbia)

“Who’s Guilty” (‘45 Columbia)

“Hop Harrigan” (‘46 Columbia)

“Chick Carter, Detective” (‘46 Columbia)

“Son of the Guardsman” (‘46 Columbia)

“Jack Armstrong” (‘47 Columbia)

top of page

|