|

Pierce Lyden Pierce Lyden

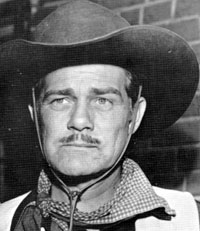

Named “Villain of the Year” in a 1944 Photo Press fan poll, Pierce Lyden became one of the best known and beloved badmen in serials and westerns, a lot of it due to his longevity and numerous western film festival appearances.

Peggy Stewart said, “Pierce Lyden was a real professional. He always knew his lines and gave his all to a particular scene. He was a fine gentleman—and he knew how to handle horses. Believe me, Pierce is no badman—just when playing the role. In later years I think Pierce found and knew more love than he had ever known. Everyone liked and knew Pierce, but it wasn’t like a Charlie King or Bud Osborne—‘cause Pierce is a quiet guy. But in later years at the festivals, he just couldn’t believe it. Then to have streets in his own hometown named after him, to go to England and be on the BBC, Golden Boot award—just all the recognition he got was awesome to him and thrilled him to death. He was quite talented…a loving person, always thinking of the other person.”

One of the sweetest, most humble, thoughtful human beings you could ever meet was born on a ranch in a sod house January 8, 1908, in Hildreth, Nebraska. Pierce learned to ride as a boy—his father (Albert Lyden) was a horse buyer for the U.S. Army. His mother, Ida Pearson, was from Illinois. As a youngster he was bitten by the acting bug when he saw traveling tent shows. Attending the University of Fine Arts in Lincoln, Nebraska, he managed to gain stage and radio experience which led to six years of stock company work in the Midwest and New England. One of the sweetest, most humble, thoughtful human beings you could ever meet was born on a ranch in a sod house January 8, 1908, in Hildreth, Nebraska. Pierce learned to ride as a boy—his father (Albert Lyden) was a horse buyer for the U.S. Army. His mother, Ida Pearson, was from Illinois. As a youngster he was bitten by the acting bug when he saw traveling tent shows. Attending the University of Fine Arts in Lincoln, Nebraska, he managed to gain stage and radio experience which led to six years of stock company work in the Midwest and New England.

In late 1931 he headed west to Los Angeles, appearing in several plays there before his expert horsemanship broke him into westerns and serials. Sporting a mustache, he was forever typed as a heavy. In late 1931 he headed west to Los Angeles, appearing in several plays there before his expert horsemanship broke him into westerns and serials. Sporting a mustache, he was forever typed as a heavy.

Reflecting on work as a badman, Pierce wrote, “The heavies always worked. There was always room for them. The good-looking boys they would hire for one picture then they didn’t want them again for a while. But the heavies and stuntmen, who did stuff I did, worked all the time. So I got stuck on westerns and serials. I made up my mind that’s the way it was going to be.”

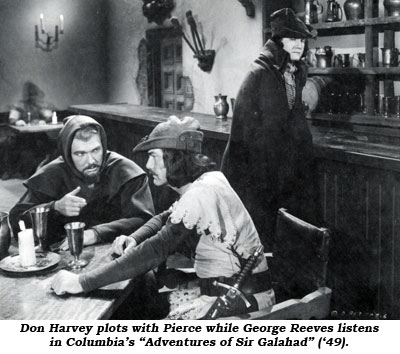

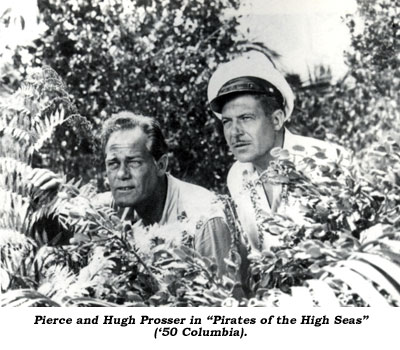

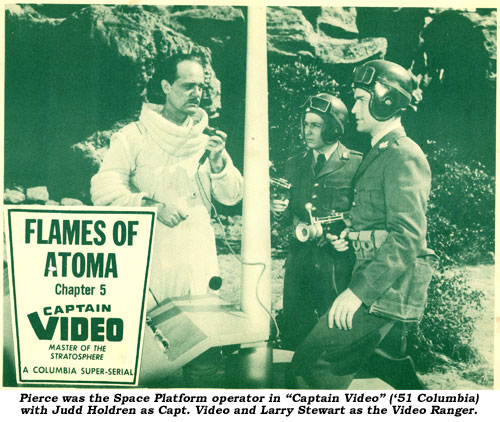

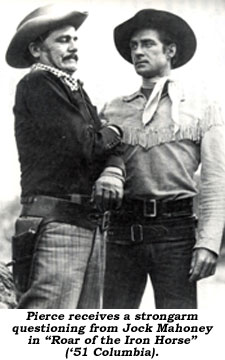

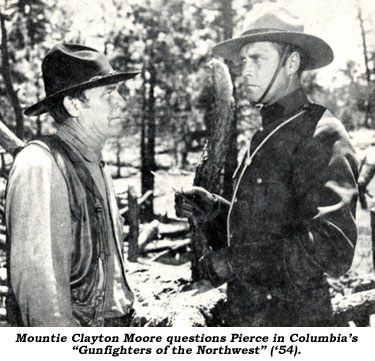

Pierce was a regular serial badman beginning with a small role in “The Green Hornet Strikes Again” at Universal in ‘41. Some of his better serial parts came in “The Vigilante” (‘47 Columbia), “Sea Hound” (‘47 Columbia), “Cody of the Pony Express” (‘50 Columbia), “Roar of the Iron Horse” (‘51 Columbia), “Government Agents Vs. Phantom Legion” (‘51 Republic) and “Gunfighters of the Northwest” (‘54 Columbia).

After appearing in “Wild Westerners”, Pierce left films in ‘62 and got into stagecraft, manning spotlights at Disneyland and later joining Johnson’s Ice Follies as property master.

Discovered by western film festivals in the ‘80s, Pierce was overwhelmed by the fact people still remembered “this old black hat” and revered his work. Since then, he’s received countless honors and awards. He was most proud of those bestowed on him by his native Nebraska, his Golden Boot award and his star on the Palm Springs Walk of Fame.

In the ‘80s Pierce authored five books about his Hollywood experiences: THE MOVIE BAD MAN; CAMERA! ROLL ‘EM! ACTION!!; FROM B’S TO TVS; MOVIE BADMEN I RODE WITH and THOSE SATURDAY SERIALS.

Pierce also found time to get involved with the Meals On Wheels program in ‘78 and was on their advisory board as its president. Besides being active in the Elks Club, he was very involved in various religious activities. He was a Mason and received several honors from that organization.

Lyden’s domestic life was not tranquil. He was once divorced, twice widowed (his last wife was Hazel who accompanied him to many festivals) and his only child, a son, died in 1988.

One of the most respected serial heavies died at 90 on October 10, 1998, in an Orange County hospice following a six month bout with cancer. Tributes came in from many of his fellow badmen. Gregg Barton: “Pierce loved the picture business and was proud of his part in it. Whether it was one or 100 in his audience, he was happy to pass on stories of the good old days. He was very serious about his career and enjoyed being the black hat baddie. In his quiet and sincere way he made you proud to have been a part of it too.” House Peters Jr.: “I never really got to know Pierce until we started going to these festivals. That’s when we became much better acquainted. It’s strange—sometimes we never saw each other on a set, even though we were on the same picture. Maybe we came in for a day or so…small part…just didn’t work the same days. And when we did, sometimes we never saw each other for another year before we got in another picture together. He was one of the steadfast black hat heavies; he sure did a whale of ‘em.” Walter Reed: “He was one of the nicest, most humble gentlemen I ever knew in the business.” John Hart: “He was a real gentleman. I’ve known him on and off for nearly 50 years. He worked in the Lone Rangers…he worked for Katzman. I’ve enjoyed knowing him and sharing One of the most respected serial heavies died at 90 on October 10, 1998, in an Orange County hospice following a six month bout with cancer. Tributes came in from many of his fellow badmen. Gregg Barton: “Pierce loved the picture business and was proud of his part in it. Whether it was one or 100 in his audience, he was happy to pass on stories of the good old days. He was very serious about his career and enjoyed being the black hat baddie. In his quiet and sincere way he made you proud to have been a part of it too.” House Peters Jr.: “I never really got to know Pierce until we started going to these festivals. That’s when we became much better acquainted. It’s strange—sometimes we never saw each other on a set, even though we were on the same picture. Maybe we came in for a day or so…small part…just didn’t work the same days. And when we did, sometimes we never saw each other for another year before we got in another picture together. He was one of the steadfast black hat heavies; he sure did a whale of ‘em.” Walter Reed: “He was one of the nicest, most humble gentlemen I ever knew in the business.” John Hart: “He was a real gentleman. I’ve known him on and off for nearly 50 years. He worked in the Lone Rangers…he worked for Katzman. I’ve enjoyed knowing him and sharing

memories of working together. Chris Alcaide: “He was a nice man—for a bad guy!” Myron Healey: “Pierce was one of the most vital, energetic fantastic men I’ve ever known. I just pray many of us can equal his mark in longevity.” John Mitchum: “I first met Pierce when I was working on the serial, ‘Perils of the Wilderness’. I was totally a greenhorn as to westerns— riding horses and all of that. Pierce kind of ‘fathered’ me. He took me aside, told me little things, helped me from going over the side of the mountain and all that kinda thing. He was so gentle and so kind that he’s been a dear friend of mine ever since…over 40 years. This is a strangely unique man. He played heavies but has not an evil bone in his body. Basically, there’s no way in real life this man could do what he’s done on the screen. If you really care about somebody for almost half a century, they have to have something most people don’t have. Pierce was one of the true gentlemen of the screen.” memories of working together. Chris Alcaide: “He was a nice man—for a bad guy!” Myron Healey: “Pierce was one of the most vital, energetic fantastic men I’ve ever known. I just pray many of us can equal his mark in longevity.” John Mitchum: “I first met Pierce when I was working on the serial, ‘Perils of the Wilderness’. I was totally a greenhorn as to westerns— riding horses and all of that. Pierce kind of ‘fathered’ me. He took me aside, told me little things, helped me from going over the side of the mountain and all that kinda thing. He was so gentle and so kind that he’s been a dear friend of mine ever since…over 40 years. This is a strangely unique man. He played heavies but has not an evil bone in his body. Basically, there’s no way in real life this man could do what he’s done on the screen. If you really care about somebody for almost half a century, they have to have something most people don’t have. Pierce was one of the true gentlemen of the screen.”

Pierce’s Serials

Jr. G-Men (‘40 Universal)

The Green Hornet Strikes Again (‘40 Universal)

Sky Raiders (‘41 Universal)

Holt of the Secret Service (‘41 Columbia)

Daredevils of the West (‘43 Republic)

The Phantom (‘43 Columbia)

Raiders of Ghost City (‘44 Universal)

Master Key (‘45 Universal)

Scarlet Horseman (‘46 Universal)

Lost City of the Jungle (‘46 Universal)

Son of Zorro (‘47 Republic)

The Vigilante (‘47 Columbia)

Sea Hound (‘47 Columbia)

Adventures of Sir Galahad (‘49 Columbia)

Cody of the Pony Express (‘50 Columbia)

Atom Man Vs. Superman (‘50 Columbia)

Pirates of the High Seas (‘50 Columbia)

Roar of the Iron Horse (‘51 Columbia)

Government Agents Vs. Phantom Legion (‘51 Republic)

Captain Video (‘51 Columbia)

Blackhawk (‘52 Columbia)

Great Adventures of Captain Kidd (‘53 Columbia)

Gunfighters of the Northwest (‘54 Columbia)

Riding With Buffalo Bill (‘54 Columbia)

Perils of the Wilderness (‘56 Columbia)

Blazing the Overland Trail (‘56 Columbia)

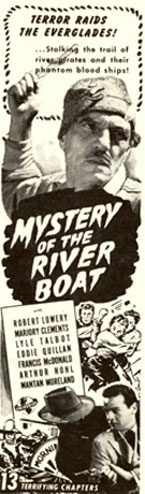

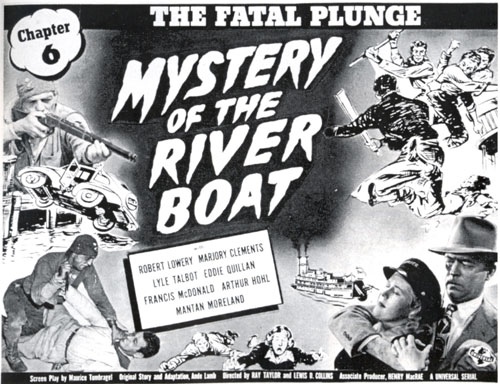

“Mystery of the Riverboat”

by Boyd Magers

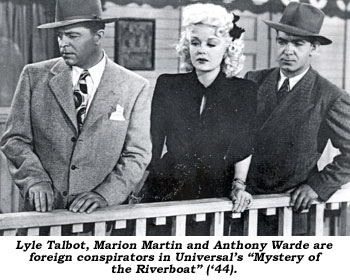

From 1925 to 1944 Henry MacRae produced 55 serials, this was his last and the 13 chapter “Mystery of the Riverboat” (‘44) is one of the oddest serials Universal ever produced. Perhaps MacRae was striving for something a little different. MacCrae and Universal injected four songs by Marion Martin into the first chapters as well as two vaudeville routines by Eddie Quillan and two numbers by former member of the Three Mesquiteers, Jimmie Dodd (who received no billing credit). All this music and tomfoolery was surrounded by mysterious happenings while on board the riverboat Morning Glory. By chapter five the serial says goodbye to the riverboat and we’re off into pretty routine serial derring-do in the Louisiana swamplands.

Were directors Ray Taylor and Lewis Collins just trying to pad out the running time of the first three chapters? Billed third, 5' 6" songstress Marion Martin serves no real purpose in the plot of the serial except for her songs. Matter of fact, although very loosely connected to Lyle Talbot’s shady faction of heavies, she bids them adios in Ch. 11 and is never mentioned again.

Dubbed “Hollywood’s Blonde Menace”, brassy Marion Martin was the daughter of a well-to-do Bethlehem Steel executive and was reared in mainline Philadelphia society. She attended exclusive schools until the family fortune was wiped out in the stock market crash of 1929. Forced to work, she found employment as a chorine in Earl Carroll’s NY stage revues. Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. spotted her and, wearing little but a feather and some beads, she replaced Gypsy Rose Lee in his Follies of 1933. Following a few other Broadway appearances and a few short films she was signed by Universal in 1938. Quickly typecast as a chorus girl or brazen gold-digger type, Martin played sexy foils to the Marx Brothers, Leon Errol in the Mexican Spitfire comedies, and others, but her film career never rose above B-status. She retired in ‘52, married, and donated much of her time to charitable causes. At 77, she died in Santa Monica, CA in ‘85. Dubbed “Hollywood’s Blonde Menace”, brassy Marion Martin was the daughter of a well-to-do Bethlehem Steel executive and was reared in mainline Philadelphia society. She attended exclusive schools until the family fortune was wiped out in the stock market crash of 1929. Forced to work, she found employment as a chorine in Earl Carroll’s NY stage revues. Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. spotted her and, wearing little but a feather and some beads, she replaced Gypsy Rose Lee in his Follies of 1933. Following a few other Broadway appearances and a few short films she was signed by Universal in 1938. Quickly typecast as a chorus girl or brazen gold-digger type, Martin played sexy foils to the Marx Brothers, Leon Errol in the Mexican Spitfire comedies, and others, but her film career never rose above B-status. She retired in ‘52, married, and donated much of her time to charitable causes. At 77, she died in Santa Monica, CA in ‘85.

Basic plot of “Mystery of the Riverboat” has three old Louisiana families—the Langtrys (Eddy Waller and heroic son Robert Lowery), the Perrins (riverboat Captain Oscar O’Shea and daughter Marjory Clements) and the Duvals (duplicitous Arthur Hohl and brother Earle Hodgins)—as co-owners of bayou swampland which just happens to contain rich deposits of Nitrolene, a quick burning fuel. Aware of the war potential of Nitrolene, the foreign faction (a country never named) of Lyle Talbot, Anthony Warde and Joe Devlin ply every underhanded trick they can muster to obtain the maps and all rights to the land. Early on, another foreigner, Ian Wolfe with henchman Dick Curtis, are also after the Nitrolene but they are quickly disposed of by Ch. 2. Basic plot of “Mystery of the Riverboat” has three old Louisiana families—the Langtrys (Eddy Waller and heroic son Robert Lowery), the Perrins (riverboat Captain Oscar O’Shea and daughter Marjory Clements) and the Duvals (duplicitous Arthur Hohl and brother Earle Hodgins)—as co-owners of bayou swampland which just happens to contain rich deposits of Nitrolene, a quick burning fuel. Aware of the war potential of Nitrolene, the foreign faction (a country never named) of Lyle Talbot, Anthony Warde and Joe Devlin ply every underhanded trick they can muster to obtain the maps and all rights to the land. Early on, another foreigner, Ian Wolfe with henchman Dick Curtis, are also after the Nitrolene but they are quickly disposed of by Ch. 2.

As Lowery and Clements fight against Talbot and his men as well as Hohl and his bayou native assistant Batiste (Francis McDonald), it seems at least half the cliffhangers involve some sort of water peril (drowning, boat crashes, hurricane, quicksand, caught in a paddlewheel, car off the pier). And Lowery should profusely thank riverboat comic steward Mantan Moreland—he saves his life over and over again. As we rush to the conclusion, the last three chapters are rife with implausabilities, truly stretching even serial credibility.

Not Universal’s shining hours, but give them credit for trying something different by injecting music in a few chapters and setting the plot in a different locale.

At the end of Ch. 11 of "Mystery of the Riverboat", knocked unconscious, the bus Robert Lowery is driving crashes into an electric power pole with a terrific electrifying explosion. But...at the start of Ch. 12 the bus crashes with no electric explosion. |

Pauline Moore co-starred with Sammy Baugh in Republic’s excellent “King of the Texas Rangers” (41). In our LADIES OF THE WESTERN book she stated, “I wasn’t a football fan. I’d never heard of Sammy Baugh before we did the serial. The only thing they asked me when I interviewed for the part was, ‘Can you run in high heels?’ (Laughs) I recall trying to climb up a rope ladder in high heels while a huge wind fan was blowing on me, and of course jumping out of the wagon and rolling down the hill. That was lots of fun. (Laughs) The only really scary part occurred when Duncan Renaldo and I were in the river. For those scenes, they took us outside of L.A. where there was a dam. (Lake Sherwood and on top of the cliff next to Lake Sherwood Dam.) They put the camera out in the middle of the dam and had us swim parallel to it. One of the grips shot marbles at us (standing in for gunshots); whenever we saw a splash we were supposed to dive under the water. I’m not a great swimmer, so for much of the sequence I was allowed to remove my heavy cowboy boots, I had on black socks so nobody really noticed. However, for those scenes of us scrambling to shore I had to have the boots on and it created a real problem. They began the take when I was about 10 feet from the bank. Right away I was in trouble. I couldn’t get my feet up, so I started to sink. Eventually, as I was going down for what seemed like the third time, one of the grips jumped in and pulled me out. I was so tired I slept all the way back to Hollywood on the studio bus. Sammy Baugh was a gentleman and very easty to work with. I thought he was most impressive, considering this was his first time in front of a camera.” Pauline Moore co-starred with Sammy Baugh in Republic’s excellent “King of the Texas Rangers” (41). In our LADIES OF THE WESTERN book she stated, “I wasn’t a football fan. I’d never heard of Sammy Baugh before we did the serial. The only thing they asked me when I interviewed for the part was, ‘Can you run in high heels?’ (Laughs) I recall trying to climb up a rope ladder in high heels while a huge wind fan was blowing on me, and of course jumping out of the wagon and rolling down the hill. That was lots of fun. (Laughs) The only really scary part occurred when Duncan Renaldo and I were in the river. For those scenes, they took us outside of L.A. where there was a dam. (Lake Sherwood and on top of the cliff next to Lake Sherwood Dam.) They put the camera out in the middle of the dam and had us swim parallel to it. One of the grips shot marbles at us (standing in for gunshots); whenever we saw a splash we were supposed to dive under the water. I’m not a great swimmer, so for much of the sequence I was allowed to remove my heavy cowboy boots, I had on black socks so nobody really noticed. However, for those scenes of us scrambling to shore I had to have the boots on and it created a real problem. They began the take when I was about 10 feet from the bank. Right away I was in trouble. I couldn’t get my feet up, so I started to sink. Eventually, as I was going down for what seemed like the third time, one of the grips jumped in and pulled me out. I was so tired I slept all the way back to Hollywood on the studio bus. Sammy Baugh was a gentleman and very easty to work with. I thought he was most impressive, considering this was his first time in front of a camera.”

Pauline Moore, 87, died December 7, 2001, of ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) at her home in Sequim, WA.

top of page |